'House of Silk': The game is afoot, in an homage with heft

12/25/2011

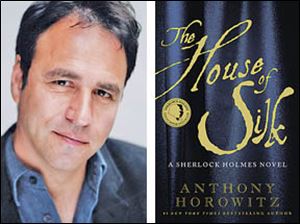

Anthony Horowitz is author of "The House of Silk."

Sherlock Holmes will never die -- no generation of writers would let him.

Someone will always lovingly gather the classic pieces -- Dr. John Watson, the Baker Street Irregulars, Holmes' smarter brother Mycroft, even the cocaine use -- and reassemble them.

Generally, whether it's a novel, a movie, or a TV series, it's either a homage to the much-loved stories, or a reimagining that takes the familiar elements into new and often darker places. Michael Dibdin's The Last Sherlock Holmes Story, which added Jack the Ripper to the mix, might be the most extreme case of a reimagining.

The House of Silk reads for most of its length like an homage. It's enormously involving and entertaining, and even funny in parts: Kindly Watson describes Scotland Yard's hapless Inspector Lestrade as having "the general demeanour of a rat who has been obliged to dress up for lunch at the Savoy."

But for large chunks of the novel, set in 1890, the reader wonders what the purpose of the new adventure is. It works just fine as a spirited Holmesian thriller, but could use more literary ambition. By the end, though, the novel shows itself to be something more. So enjoy the ride, and be assured it's going somewhere.

The House of Silk is presented as a Holmes story too disturbing for Watson to publish in his lifetime. Aging, and suffering from an old war wound, as a new "terrible and senseless war rages on the Continent," Watson plans to instruct that the tale be embargoed for 100 years. "It is impossible to imagine what the world will be like then . . . but perhaps future readers will be more inured to scandal and corruption than my own would have been."

A big challenge for Horowitz is juggling two separate inquiries with bewildering links to each other.

The first one begins when Edmund Carstairs, a fine-art dealer from Wimbledon who feels menaced by a man in a flat cap who he believes has followed him from America, engages Holmes to investigate. Carstairs had been the accidental victim of a train robbery in Massachusetts that led in the ensuing weeks to half a dozen killings.

The second inquiry begins when young Ross, one of the Baker Street Irregulars, is found beaten to death, his throat cut, and a white silk ribbon knotted around his wrist.

An uncharacteristically shaken Holmes tells Watson: "Wiggins, Ross, and the rest were nothing to me, just as they are nothing to the society that has abandoned them to the streets, and it never occurred to me that this horror might be the result of my actions. Would I have allowed a young boy to stand alone outside a hotel in the darkness had it been your son or mine?"

Holmes and Watson learn that the House of Silk "is a criminal enterprise that operates on a massive scale and ... has friends in the very highest places." It's also, as Holmes tells Carstairs at the end, "a crime more unpleasant than any I had ever encountered."

Horowitz, whose novel is officially sanctioned by the Conan Doyle Estate, has written novels and plays. His television work includes Foyle's War, a thoughtful murder-mystery series that takes place in England against the backdrop of the biggest mass murder of all, World War II. Horowitz gets Watson's essence -- a decent man whose keen intelligence will always be eclipsed by Holmes'.

Classic tales such as the Arthur Conan Doyle stories carry the ideals and anxieties of their age, and of later ones. The House of Silk capably does the same. Early on, Watson expresses a regret: "It sometimes occurs to me now, having witnessed so many momentous changes across the years, that I should have described at greater length the sprawling chaos of the city in which I lived," a London where wealth and poverty "were living uneasily side by side."

In many ways, that tension is at the heart of The House of Silk, and Horowitz's Dr. John Watson does a better job than he gives himself credit for.