Lima's victory in keeping refinery told in new book

Bluffton U. professor recounts cooperation

7/23/2012

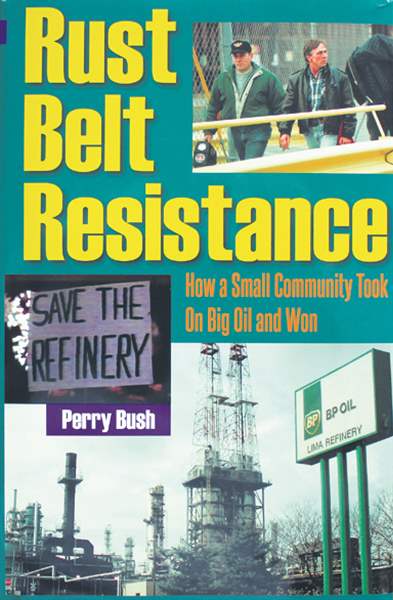

Cover of Rust Belt Resistance by author Perry Bush, professor at Bluffton University. documents the events in the 1990s in Lima, where disparate groups united for a goal.

Cover of Rust Belt Resistance by author Perry Bush, professor at Bluffton University. documents the events in the 1990s in Lima, where disparate groups united for a goal.

It's a story we don't often hear -- rather than a plant closing in a Midwestern city, workers, elected officials, and community members pull together and save it, keeping hundreds of jobs and millions of dollars in the community.

It happened in Lima in the 1990s, and a history professor at Bluffton University has documented the events surrounding saving the city's BP oil refinery in a new book, Rust Belt Resistance: How a Small Community Took On Big Oil and Won.

British Petroleum announced in 1996 that it would close and demolish its Lima refinery; the move would have put at least 500 people out of work.

Author Perry Bush said he was drawn to the story because of his proximity to the people and places involved and because of the David-and-Goliath themes of the choices local officials and communities have when faced with the prospect of losing a major employer.

"[The story] mattered. It spoke to all these issues that I think are important -- about corporate power, about community agency," Mr. Bush said, speaking in his book-filled office on a recent morning.

"This is not just a Lima story. It is unique, but the larger factors that led this corporate partner to [try to] close the plant, that is not an uncommon story."

He has been working on the book since 2001; it was published this year. Mr. Bush recently returned from spending a semester abroad as a Fulbright Scholar in Ukraine, where he was teaching American history at a university.

Perry Bush, whose research usually focuses on the Mennonite community, says his book's story is not just Lima's.

The book came out while he was overseas. The subject matter was a departure from his usual research, which typically focuses on the Mennonite community.

He said he strove to make the book readable to the general public and not only for academics.

"I want to move people," he said. "You just can't move folks by writing wooden prose that only a dozen scholars in the United States would appreciate … I want to draw people in."

The story Mr. Bush tells outlines Lima's history: its strong ties to oil -- he describes it as the epicenter of the American oil industry from 1885 to 1901 -- its manufacturing heritage as a builder of locomotives, tanks, cranes, autos, and other products, and the waves of devastating plant closings that struck Lima beginning in the 1980s.

Instances of communities saving a plant from shutdown after a corporate decision has been announced are exceedingly rare, said Barry Bluestone, an expert on deindustrialization and director of the Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy at Northeastern University in Boston.

"There are very few cases I can think of in which a popular movement has saved a plant," said Mr. Bluestone, who grew up in Detroit.

In one instance, where local pressure did keep a General Motors Corp. plant in Massachusetts open for an additional decade after an announced closure, the facility ultimately closed, he said.

"It is rare that these [communities] are successful," he said.

Mr. Bluestone said he was not familiar with the Lima story, but in order for a community to reverse a planned shutdown, several factors are key: employees and managers working closely to improve productivity and increase efficiency, and effective local government that understands what businesses need to be competitive.

Tom Leary, an associate professor of applied history at Youngstown State University, citing community coalitions to save Youngstown steel mills in the 1970s, said a community's success or failure is also tied to the specific facility and specific industry at stake.

Mr. Bush attributes the happier outcome in Lima to factors such as sheer good luck, committed community activism, a strong work force, and a profitable plant that was attractive to another corporation.

The facility was sold to Clark Refining and Marketing in 1998, an outcome that would not have been possible, Mr. Bush believes, without the advocacy of the mayor and other community members or without the commitment of the plant's work force, which kept the facility profitable and improving, even after news of the impending closure. Mr. Bush said disparate factions in Lima pulled together, such as the city's Democratic mayor and conservative county business leaders.

"In the end, when push comes to shove, they weren't going to let BP throw their city away," he said. The refinery is still operating today, making about one quarter of the gasoline consumed in Ohio. It is now owned by Husky.

Mr. Bush said that although the Lima situation is an anomaly, the events surrounding the refinery's rescue still have lessons for communities.

Lima Mayor David Berger, a central player in the sale, agreed. Though there are times when plant closures are inevitable, the facility in this instance was still competitive, he said. "Often, it appears that we can do nothing," he said. "But if we engage, and we do pay attention, then we can create other alternatives for our communities."

Mr. Bush said, "The moral of the story is -- be active. Don't take it lying down."

Contact Kate Giammarise at: kgiammarise@theblade.com or 419-724-6091.