BOOKS

Toledo native’s past shapes novel

Story set in city’s ‘Little Syria’ neighborhood

11/4/2012

Joe Geha will be at Barnes and Noble, Monroe Street, at 6 p.m. Thursday and will speak at 5 p.m., Nov. 13 in room 2100 of the University of Toledo Field House. UT information: 419-530-2086.

Lebanese Blonde is not about a sultry woman.

You might figure that out from the cover of this new book; a blurred photo of 19 brunette adults of the Geha family on the porch of 615 Chestnut St.

Set primarily in North Toledo’s Little Syria neighborhood in the mid-1970s, it’s a coming of age story blended with the immigrant experience of adjusting to life in an often perplexing America.

Most of the characters are immigrants: women who pour love into the aromatic Middle Eastern dishes they cook, Uncle Waxy, who runs a fading mortuary, and Teyib, the odd newcomer with a checkered past who worms his way into some of their hearts. The protagonist is good-hearted Samir, 23, the accomplice to his slightly older cousin, Aboodeh the unscrupulous.

Lebanese blonde is what Aboodeh and Samir arrange to import in hidden cavities of caskets shipped from Beirut to the mortuary: it’s a desirable strain of pure and potent hashish.

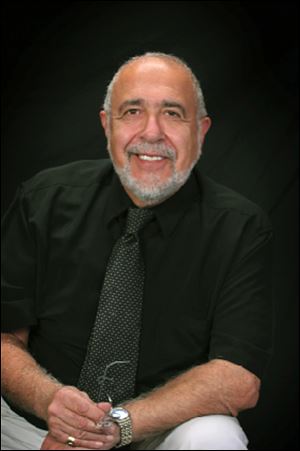

“I identify a lot, but not entirely, with Samir,” said Toledo native Joseph Geha, who wrote the 285-page novel and will appear at two upcoming events. “In college I had friends who were involved in drug deals; in fact, one was killed.”

In 1971, he was touring historic Baalbek in Lebanon when he saw men strapped with AK-47s who were guarding nearby hashish (cannabis) fields.

Geha, 68, is retired from teaching writing at Iowa State University. He graduated from St. Francis de Sales High School, and earned bachelors and master’s degrees at the University of Toledo. He was 2 in 1946 when his parents and two siblings boarded the Vulcania for a better life; his sister had typhoid fever that his father had initially covered up but it was discovered en route, resulting in the ship being quarantined when it reached Ellis Island in New York.

“Coming of age you’re finding out where you are in this life. You take responsibility for where you came from, who you are, and what you choose to do. You realize life isn’t fair but go on anyway.” And the immigrant, “in a way, is like a baby.”

Geha spoke Arabic when he started school and was, of course, teased. As a Cub Scout, he was confounded by what the Webelos were.

“I tried to do a story about that once, trying to join a culture when there’s a sense of powerlessness and not knowing and not fitting in.”

He drew from own well to create two key characters. “Teyib and Samir, they’re both me, in a way.”

“Samir comes from a part of me that holds back for fear of losing that which immigration and naturalization will eventually take away from us — language, customs, food, culture, even family and a sense of home. Little Syria was never meant to be a permanent refuge, and by 1975 it’s fast disappearing. Therefore, Samir, who’s not at all savvy to start with, must make the journey toward knowledge of the greater world and of himself.”

Teyib, which translates to “tasty,” was in a previous short story.

“In both that story and in the novel he arose out of a part of me that remembers what it was like to be an alien, speaking and thinking my thoughts in Arabic, and trying, maybe too eagerly, to adapt to this new, American world just outside my doorstep. He is both savvy and clumsy, just as I was.”

Geha’s father owned grocery stores in Toledo, including one at 901½ Monroe St., above which the family lived.

“When I first discovered I could write was in the seventh grade at Cathedral School when our teacher, after giving us an in-class writing assignment, didn’t believe that I had written it myself. The principal was called in to read it as well. In her office, as I listened to them going over some of my phrasing, I remember thinking to myself, ‘Hey, that was pretty good.’ ”

He taught creative writing in Iowa and some of his short stories, poems, and plays were published in literary magazines. He contributed to Arab Americans in Toledo (2010, University of Toledo Press) and about 15 years ago, began writing Lebanese Blonde.

“I wrote another version which I abandoned. I wasn’t making something well-connected [including] the story line and characters of Samir, Teyib, and Aboodeh. Nobody was banging on my door for the next pages so I took my time with it.”

After retiring, he undertook a third version in 2003, determined to finish, so he wrote a couple of hours a day, six days a week.

“I don’t enjoy writing. It’s very hard to turn off my internal critic. When you write creatively, you need to shut that down as best you can and play. I believe most creativity comes out of playing.”

The first couple of publishers he sent Lebanese Blonde to didn’t nibble. But years earlier when he was still teaching, he’d been contacted by the University of Michigan Press and saved the card of editor Chris Hebert.

“I wrote him and he agreed to have a look. He had some suggestions for revisions that were very helpful,” he said. “I’m not a terrific story teller.” Hebert, for example, advised Geha to provide more detail about how much was at stake for Samir.

UM Press started publishing fiction that had a midwestern connection about 10 years ago, worthy novels that might not otherwise stand a chance in an industry that’s largely located on the coasts, said Hebert.

“I’m very selective,” said Hebert, author of The Boiling Season, set in Haiti. “Right from the start Geha had a really amazing cast of characters.”

Lebanese-Americans are underrepresented in literature, he added. “I really liked learning about this community. And I love the humor in it.”

The father of two daughters, Geha lives in Ames, Iowa, and is married to Fern Kupfer, teacher and author of four books including Before and After Zachariah, a true story of family life with a severely disabled child. He paints, practices archery, travels to the Dominican Republic on medical missions, plays poker, cooks, and teaches cooking.

“ I acquired a cookbook put together by the Ladies’ auxiliary of St. Elias Church. Every weekend I taught myself a recipe from that book, first calling my mother and ‘correcting’ the recipe according to how she made a particular dish. Years later, her last words to me before she died, was after she’d tasted a spinach tartlet she’d taught me how to make. I’d brought her a few to the hospital; she thanked me and, sick as she was, tasted one for my sake. Later, as I was leaving for the evening, her last words: ‘Next time, more lemon.’ ”

Joe Geha will sign copies of his books at 6 p.m. Thursday in Barnes and Noble on Monroe Street, and will speak at 5 p.m. Nov. 13 in Room 2100 of the University of Toledo Field House. UT information: 419-530-2086.

Contact Tahree Lane at tlane@theblade.com or 419-724-6075.