Coming to terms with mental illness

12/9/2012

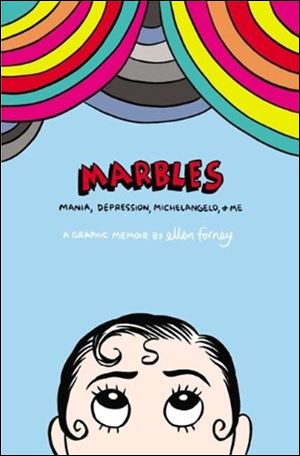

Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo and Me by Ellen Forney (Gotham, 256 pages, $20 paperback).

There’s a glorious manic edge to Ellen Forney’s Marbles, a graphic memoir about the artist’s battle with depression. Forney is bipolar, which means she suffers manic episodes, as the book recounts. Yet even more, it’s a function of how she puts Marbles together, by turns methodical and frenzied, as if channeling her emotions on the page.

In that sense, the book reads less like a comic than a scrapbook, in which traditional strip-style layouts alternate with lists, sketchbook pages, re-created photos — all to reproduce the chaos of her inner life.

Forney has been producing work like this for many years. Her previous strips have been collected in I Love Led Zeppelin and Monkey Food (which looks back at her childhood in the 1970s); she also illustrated Sherman Alexie’s National Book Award-winning young adult novel The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian.

What these efforts share is a quality of engaged irreverence, a sense that Forney is standing on the outside and the inside at once. This is a nearly perfect metaphor for depression, which equally enlarges and diminishes her as she careens from the manic to the subdued.

“Memory is mood-specific,” she tells us, by which she means that “[m]y memory of what it was like to be depressed was fuzzy, and heavily-influenced by my mania. ... My euphoric mind just couldn’t conjure up that dramatic shift within itself.”

The challenge of Marbles is to evoke the two sides of this elusive whole, to remember both the moods and her back-and-forth between them, and to fashion all of it into a coherent narrative.

There are significant risks to such a project, and not just because there’s been a glut of memoirs about depression in recent years. But Forney pulls it off because she’s relatively fearless, both about the difficulties of what she’s undertaken and about revealing herself.

She introduces her first depressive episode with a sketch on lined paper of a wide-eyed figure clinging, by its fingernails, to the edge of a cliff. “I was slipping down and there was nothing I could hold onto,” she writes, a line that highlights the two voices that motivate her work here: the one that’s living in the moment, and the one that’s looking back.

This is an essential tension, not just for Marbles but in regard to the memoir in general; it’s a form that relies on a kind of double vision, the story as it was lived and the story as it is being told. Caught up in the experience (as we know because she tells us), Forney was sure she would never come out of it. In that sense, if her book has one essential message, it is that she survived.

Marbles is more than a survivor’s story. It is a book about Forney’s struggle to come to terms with herself, which is similar to the struggle everyone faces. The best stuff here collapses the distance between reader and artist, by stripping away distinguishing details or by opening the story to broader concerns.

Forney also takes on the question of identification explicitly, conjecturing about the relationship between mental illness and art. “Isn’t ‘crazy artist’ just a stereotype anyway?” she wonders, after reading Kay Redfield Jamison’s Touched With Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament, which features a list of painters and writers (Gauguin, Van Gogh, Michelangelo, Munch, Artaud, Poe, Plath, Whitman, Pound) who likely suffered from depression. “How do ‘they’ know these people were crazy? ... Did their moods affect their work?”

At the heart of Marbles, is a sense of terror: both the terror of depression and the terror of not knowing who you are. For Forney, these artists help to root her, and when, late in the book, she imagines 20 of them — names, faces, birth and death dates all clustered around her head in the form of overlapping thought balloons — it feels like a victory.