Charles Manson biography presents some surprises

8/17/2013

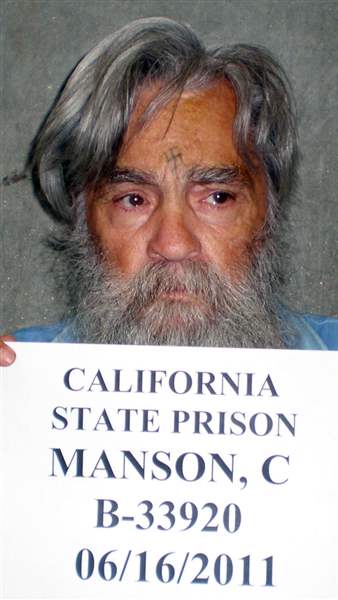

In this photo taken June, 2011 and provided by the California Department of Corrections, Charles Manson is seen in a mugshot from Corcoran State Prison.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

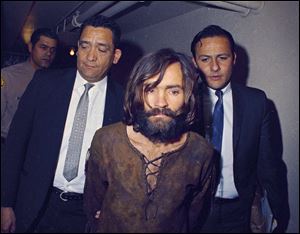

This 1969 file photo shows Charles Manson being escorted to his arraignment on conspiracy-murder charges in connection with the Sharon Tate murder case.

On an oppressively hot night in Los Angeles in the summer of 1969, followers of Charles Manson broke into Hollywood movie director Roman Polanski’s house and stabbed, shot, and bludgeoned to death five people on the premises, including Polanski’s wife, actress Sharon Tate. The next night, Manson’s followers stabbed to death the LaBiancas, an upper-middle-class couple.

In both instances, some of the victims were stabbed so many times that any one of a number of wounds would have been fatal. Moreover, messages were written at the scenes in the victims’ blood: “Rise,” “Healter Skelter” [sic], and “PIG.” “War” was carved in one victim’s abdomen, and a knife and fork were left thrust into his body.

Jeff Guinn, former book editor of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, knows how to tell a story, and he scores some coups with Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson. He interviewed people previously overlooked in the Manson narrative, including for the first time Manson’s sister and a cousin.

The new information provides some surprises, particularly in the photographs. News photos usually depict Manson looking wild-eyed. But a previously unpublished photo in Guinn’s book shows a smiling, sweet-faced boy, with just a hint of calculation in his sideways glance. Another snapshot is of Manson’s first wedding, with Manson in a conservative suit and his West Virginia bride looking fresh-faced and wholesome.

Manson’s biological family members (as opposed to his followers, called collectively “The Family”) also refute the common view that Manson was the bastard son of a teenage prostitute who abandoned him. Although Manson himself refuted this portrayal in Manson in His Own Words (1988), Guinn does by far the best job of uncovering Manson’s family and their lives.

He details the life of Manson’s mother, the rebellious daughter of a fundamentalist rural Kentucky widow. Technically, Manson was not the son of an unwed mother — his mother married William Manson, his stepfather, before he was born. And she did not abandon him. Instead she served time in the infamous Moundsville, W.Va., state prison for a botched robbery.

While his mother was in prison, young Manson lived with extended family in McMechan, W.Va., about 63 miles southwest of Pittsburgh. There Manson displayed ominous tendencies. He lied, stole, had a frightening temper, and “became fascinated by knives or anything else that was sharp,” Guinn writes.

In this photo taken June, 2011 and provided by the California Department of Corrections, Charles Manson is seen in a mugshot from Corcoran State Prison.

He went back to his mother when she got out of prison. But his mother remarried, this time to an alcoholic. As she tried to keep her troubled marriage afloat and as Manson’s behavior deteriorated, she placed her son in the first of a succession of institutions.

Guinn interviewed Manson’s acquaintances, friends, fellow inmates, and court bailiffs, and seems to have read virtually every scrap of documentation about Manson and his times. He charts the development of Manson’s ability to manipulate, an ability honed through years of research and practice. And he gives concise, forceful accounts of Manson’s time and place.

In 1967 the San Francisco neighborhood of Haight-Ashbury hosted a “Be-In.” The media “accurately captured the rapturous atmosphere,” Guinn writes, and young people began flocking to the neighborhood. When the reality of overcrowding and lack of shelter, food, or medical treatment sank in, many people went back home. The ones who stayed, Guinn writes, were “the ones with no social skills who had trouble making friends or fitting in back in their hometowns, or else were at critical odds with their parents and wanted someone more understanding to take them in and tell them what to do.”

Manson culled his Family from these youths. He bent them to his will with LSD, sex, and isolation, plus his ability to divine and exploit their weaknesses. Meanwhile, he pursued his dream of being a music star, gaining entree to some of the industry’s biggest players.

When the record deal he believed should be his did not materialize, life with Manson became stranger and much scarier.

Manson told his followers about “Helter Skelter,” a massive race war from which they would emerge as the rulers of the world with Charlie at their helm. When black people seemed in no rush to start massacring whites, Manson ordered the Tate-LaBianca killings to get the race war started. Or, so goes the line of reasoning that emerged in court and in prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi’s best-selling book Helter Skelter.

But Guinn presents convincing evidence for another theory that has been previously floated. The two homes at which the killings took place were the former home (or next door to the former home) at which had lived people who had failed to get Manson his record contract.

Manson’s last parole hearing was April 11 last year. He comes up for parole again in 2027, if he is still alive.

Guinn has written many other books, notably Go Down Together: The True, Untold Story of Bonnie and Clyde, a finalist for the Edgar Award. This book on Manson will add to Guinn’s reputation as an author who can both research and write well.

The Block News Alliance consists of The Blade and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Laura Malt Schneiderman is a reporter for the Post-Gazette. Contact her at: lschneiderman@post-gazette.com.