‘Ghosts of Happy Valley’ is a charmer

10/12/2013

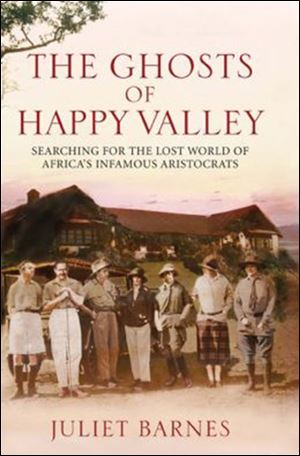

Juliet Barnes’ book The Ghosts of Happy Valley turns on five elements for its considerable charm. The first is a virtually universal phenomenon that nearly everyone has experienced — the desire to see houses where either oneself has lived in the past, or where someone well-known has lived, to see what state it is in now, what has happened to it in the meantime.

The second is the notoriety that has continued to accrue to a group of British and other near nobility who lived in the then British colony Kenya in the period 1920-50. Their behavior has to be considered outrageous in the context of the times, including as it did spouse-swapping and major abuse of alcohol and drugs, including heroin and cocaine.

The particular area that was the focus of their lives included a fertile river valley under Kenya’s Aberdare Mountains that came to be called Happy Valley, based on their not always felicitous frolicking. The “happiness” ended in some cases in suicide and murder.

The third interesting string to the story is to trace what the whites in Kenya were doing across the years against the background of Kenya’s own path to independence. This included Kenyans participating as British soldiers in World War II, realizing that white people, too, died when they were shot or knifed, and coming home to Kenya unwilling to remain as servants and small farmers while foreigners lived well on their land.

Then came Mau Mau, in the 1950s, when members of one Kenyan tribe, the Kikuyu, rose up and attacked settlers and other colonists, killing 32 of them. The Kenyans achieved independence in 1963. The British government bought out some of the settlers at that point. Happy Valley changed hands.

The fourth element in Barnes’ book that adds considerable color and charm is the absolutely beautiful scenery within which the book is set. She describes in some terrific descriptive writing the mountains, streams, forests, and vistas as well as the wildlife within which the Happy Valley crowd, the Kenyans, and she live.

I have seen some of what she writes about, although I did not have the opportunity to explore Happy Valley as she did, nor with the rich background of knowledge of the people who lived in Kenya and live there now from which she works.

The fifth string consistent throughout the book is her portrait of the Kenyans at their best — especially their ineffable, unfailing hospitality — and at their worst in the form of the ravages that some of them have worked both on the old houses and on the environment.

I say “some of them” because the most endearing character in the book is Solomon Gitau, a Kenyan totally dedicated to the conservation of the fauna and flora of the country. Gitau, in explaining the destruction that has occurred to one of the houses, says, as if explaining to a child, “That is Africa.”

If there is anything wrong with the book it is that after a while it becomes difficult to keep the cast of characters, the relationships among them, and the houses and farms she visits straight. As both a strength and a weakness of the book, Barnes, herself of British origin living in Kenya, a descendant of families there, knows the people very well, sometimes too well. This person was the third wife of that person, who was the son of the second husband of another person. I had the same problem with War and Peace, although the translator of that provided the reader a glossary of the characters.

The people who populated Happy Valley at its high point, partying and carousing massively, were quite something. Two of the most interesting women were Lady Idina Sackville and Countess Alice de Janze. Both were promiscuous. A third siren was described by an observer as “no one-man mare.” Idina married five times. Alice, born in Chicago, committed suicide. The dominant event of the Happy Valley story was the murder of Lord Josslyn Hay, Earl of Erroll, shot dead at a crossroads, which I have visited, just outside Nairobi, Kenya’s capital, in 1941. He was known for his ability to bring women to quick and easy orgasm.

Many husbands and lovers and ex-lovers were suspected of having dispatched him. The killer has never been firmly identified to this day, and it is virtually certain that anyone who knew the truth is now deceased.

Barnes continues a quest to learn the killer throughout her travels in Happy Valley, and drops clues she discovers throughout the book but arrives at no conclusion. One suspect was the British intelligence service.

I raced through the book and recommend it heartily. It is sometimes confusing but consistently charming.

The Block News Alliance consists of The Blade and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Dan Simpson is a former U.S. ambassador to several African nations who writes for the Post-Gazette. Contact him at: dsimpson@post-gazette.com.