With memoir 'High Notes,' Richard Loren shares tales of times with music's biggest acts

11/16/2014

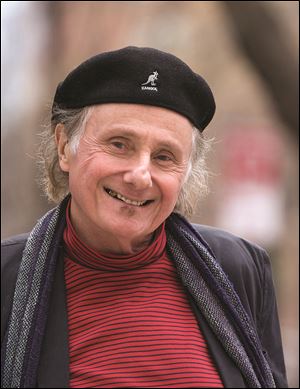

Music author Richard Loren is now 71 and lives in Maine.

Richard Loren spent nearly two decades working with three of the biggest acts in rock and roll, the Grateful Dead, the Doors, and Jefferson Airplane.

And yes, he the stories to go with it: Bailing Jim Morrison out of a New Haven, Conn., jail after the singer was arrested for yelling the F-word during the concert and charged with "breaching the peace," "immoral exhibition," and "resisting arrest." Smuggling drugs across the Canadian-U.S. border for members of Jefferson Airplane. And orchestrating the Grateful Dead's triumphant three-night stand at the Great Pyramid in Egypt, a near-impossible concert event that 36 years later remains Loren's proudest achievement.

After regaling family, friends, and acquaintances with his adventures as an agent and manager, Loren decided to share those stories and many more via a new book.

High Notes: A Rock Memoir ($14.99, highnotes.org or amazon.com) is a self-published chronicle of his roller-coaster ride through the music world, beginning with a run of Liberace big-tent concerts in Baltimore in 1966, to managing Jerry Garcia and later the Grateful Dead during arguably the band's creative peak in the 1970s. Loren quit the band and the music business in 1981.

The 71-year-old Loren lives on the Maine coast, and The Blade recently spoke with him by phone from a hotel in Portland.

Q: So why did you write this book?

A: The book is not about the Grateful Dead. It's not about Jim Morrison. It's about a young kid growing up in this scene and telling a few stories about the people he met along the way and how it changed his life. It's a rite of passage story, really. And that's what I tried to achieve. I didn't want it to be a pain to Jerry Garcia or an adjuration of Jim Morrison. We all have our ups and downs and our attributes and our weaknesses, and musicians have that just as well.

To me it was gratifying to get the stories out. It was a soul-searching experience to look at yourself as a human being and your behavior through life, and when things went wrong, why they went wrong. And that’s one of the points I tried to make in the book. It’s important for people to just look back on their behavior and what to do, and that’s one of things that I really learned.

Q: How did your career get started?

A: I was a young kid, in my early 20s, and I didn’t really plan to get into the music business. I was going to be a chiropractor, and then I fell for this girl in college and the next thing you know I was in the drama department and starting to get involved with theater people. I just changed my major to English and all of sudden I thought I wanted to start a repertory theater. I got this break where I was a theater manager in Baltimore at one of those tent theaters that they used to have back then across the Eastern seaboard. Liberace was a performer there that last week. He introduced me to his agents and said good things about me, and the next thing you know I was sitting behind a desk in New York as a full-fledged agent in an agency that really didn't have any rock talent for me to book. And those were the kinds of people that the colleges wanted at that time. I didn’t have any of those artists, so I had to go trawl for talent in Greenwich Village. I was really very lucky or ambitious, and I wanted to keep my job. And then I managed to get the Jefferson Airplane and then my career just took off from there.

Q: So how much of your success do you attribute to your ambition and how much to plain luck?

A: That’s one of the things I address in the book: synchronicity, coincidence, why do things happen? It’s like, I never could really answer that and that’s one of the questions that I was curious about. I am ambitious and my ambition was to be successful and when I got into that business I just wanted to make it happen. And then I became totally absorbed in it, when I started to befriend these musicians. That was the really important connection for me because I really felt I met the people I wanted to be around. I left the business end of it because the avarice of the industry just turned me off. I bonded with the musicians rather than to follow up on my opportunities in the real business.

When I met the Grateful Dead I was able to be the businessman that I trained to be in running their organization, but I did it within their cocoon. The Grateful Dead didn’t trust the suits. They didn't want to deal with people outside, they tried to do everything themselves, and in the beginning they could pull it off. But later they needed to have some expertise and not to have to go outside to get what was good for them ... and I just became part of the family. [I] happened to be the guy that had business sense and could help them keep their affairs in order.

Q: Did you ever feel too close to the band, to where you couldn’t make difficult decisions because of that friendship?

A: No, not at all, especially with Jerry. Jerry being my friend and being very astute and a very bright guy [who] knew what [the band] wanted to do and what they didn't want to do. We shared an office every morning for 10 years; he would come into my office. It was an office separate from the Grateful Dead because I got that office with him when I was working with just him as a personal manager, before I was involved with the Grateful Dead. We conducted business there, and I felt it to be very comfortable to be friends with the people you’re doing business with and these musicians trusted me and it was like being in heaven, in a way. It was difficult later when I had to manage them; I was very fiscally conservative and they wanted to do what they wanted to do and had these big expenses.

Q: At some point in the 1970s, the Grateful Dead and their tours got so big, with so many people dependent the concerts as their source of income, they couldn't or wouldn't stop playing. Do you think the Grateful Dead became too big?

A: I really do. I left them in 1981 because of the obvious reasons: Jerry’s substance abuse was dragging him down and I in a way lost him as a friend. He got involved with other things and got more involved with his drawing. We didn’t have the connection anymore. It was really getting to be too big. Living life in the fast lane, I’d had enough, really. It was really taxing. I would wake up in the morning nervous and have adrenalin rushes every time a musician would walk in the door. I’d say, “Oh god, now what do they want? Now what do I have to deal with?” It was really affecting my life negatively.

To me I think their best music was really in the ‘70s myself. I think that maybe later on some of the music got a lot more sluggish, I’m glad that I got out when I did, quite frankly.

Contact Kirk Baird at: kbaird@theblade.com or 419-724-6734.