DEADLY ALLIANCE: WEAPONS OVER WORKERS

'Stonewalling:' Federal judge rules Brush concealed documents

1/17/2013

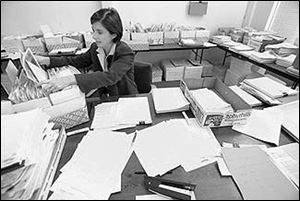

Ann Rowland, an attorney with Rowland & Rowland of Knoxville, Tenn., represents workers with beryllium disease. She says she caused a stir when she dressed in protective clothing and a gas mask to examine documents that a court had ordered Brush to deliver.

KNOXVILLE, Tenn. -- When it comes to worker safety, Brush Wellman says it has nothing to hide.

But a federal court here in 1996 sanctioned the company for deliberately concealing potentially damaging documents about the dangers of beryllium. For this and related misconduct, Brush Wellman had to pay $175,000.

"Brush Wellman's conduct has gone beyond gross negligence," U.S. Magistrate Judge Robert Murrian wrote in the case. The company's "deliberate indifference" and "intentional failure to produce documents ... demonstrate a pattern of abuse that should be dealt with firmly."

Lawyers for beryllium disease victims say the case further proves that Brush Wellman is hiding from the public what it knows about the dangers of beryllium and when it knew it.

"They withheld documents until they were caught," says Ann Rowland, the Tennessee attorney who won access to Brush's records.

Brush Wellman would not comment, other than to say that one of its lawyers was to blame.

DEADLY ALLIANCE: How government and industry chose weapons over workers

The penalty was among the largest of its kind in Tennessee. But the case is also noteworthy for what happened in the middle of the dispute, when Brush released some of its records.

Twelve boxes of documents were delivered to Brush's Cleveland law firm, Jones, Day, Reavis & Pogue. There, Ms. Rowland, who had been fighting for the records for months, began to review them in a conference room.

But she says she noticed the boxes were old and dusty. "I thought, 'Oh, my God! Is this beryllium?' "

Using baby wipes, she took dust samples of the boxes. She dropped each sample into a plastic bag and express-mailed them to a lab for analysis. When the results came back, she says, they revealed beryllium.

Furious, she got a court order for Brush to provide clean boxes. The company complied, and the records were delivered to a court reporter's office a few blocks from Brush's law firm.

This time, Ms. Rowland didn't take any chances: She says she returned to the records wearing protective clothing and a gas mask.

Brush's lawyers, she says, "just about croaked. They hate my guts."

Under the court sanction, Brush had to pay $175,000 to Ms. Rowland's Knoxville law firm, Rowland & Rowland, for the time she spent fighting for the records.

She originally had sued Brush in 1992 on behalf of two workers who developed beryllium disease after working at Robertshaw Controls, a Knoxville company. Brush was named a defendant, she says, because it supplied beryllium to the other firm.

As part of the lawsuit, Ms. Rowland asked that Brush turn over all pertinent records. Legally, Brush had to comply.

But it didn't, court records show, and the two sides spent the next year fighting the issue in court.

Numerous hearings were held, motions filed, and orders handed down. One hearing had no fewer than 17 lawyers present.

"It looked like a bar convention," Chattanooga attorney Barry Gold recalls.

U.S. District Judge Leon Jordan ended another hearing by admonishing Brush: "This court will not put up with any stonewalling any longer."

But the problems continued.

Twice, the federal court ordered Brush to turn over its records. Twice, Brush violated the orders.

Finally, Magistrate Judge Murrian became fed up. In a strongly worded opinion, he said that although Brush had turned over 60,000 documents, whenever opponents "found a trail which might shed light on what Brush Wellman knew about" key issues, "they have run into a stone wall."

He was particularly upset over a critical document that he said Brush's in-house lawyer, John Pallam, deliberately concealed. He said Mr. Pallam not only made "a bogus claim" that the record was exempt from disclosure, but he later tried to blame his secretary for the transgression.

Magistrate Judge Murrian concluded that he had no choice but to take a drastic step: He would recommend that Brush forfeit the entire lawsuit, leaving only the question of how much money the ill workers should get.

But Judge Jordan thought that penalty was too severe. He ruled that a $175,000 sanction was enough.

Mr. Pallam, Brush's in-house attorney who was found to have concealed a document, would not comment on the case.

In court filings, Brush maintained it was not concealing records. It blamed the Tennessee lawyer it hired to handle the case, Stuart James, for the problems.

Brush said Mr. James didn't inform the company of the seriousness of the problems; otherwise, all documents would have been released.

Mr. James says: "The court sanctioned Brush Wellman for its conduct and ended up not sanctioning me. I think that speaks louder than anything that Brush Wellman could say."

But the court did fault Mr. James: "He is to blame for many of the difficulties... ." He was referred to the court's chief judge for possible discipline but that judge said discipline was not warranted.

Meanwhile, the lawsuit that started the whole document dispute was settled out of court, with Brush giving the two ill workers an undisclosed amount of money. Ms. Rowland, their attorney, would only say that "it was a lot."