OHIO

Roberta's Law informs victims of parole tries

New legislation gives notice of hearings automatically

3/31/2013

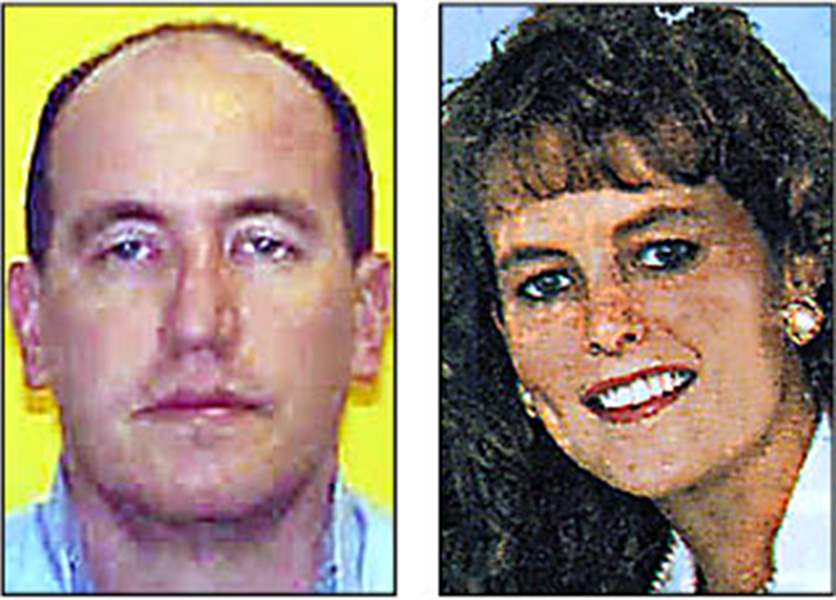

Jeffrey Hodge abducted and killed University of Toledo student Melissa Anne Herstrum in 1992.

Jeffrey Hodge abducted and killed University of Toledo student Melissa Anne Herstrum in 1992.

Diane Herstrum dreads the day her daughter’s killer comes before the Ohio Parole Board, but she knows one thing for sure: She will be there.

In 2004, the Rocky River, Ohio, woman lobbied for a change in state law to permit victims of violent crime or their survivors to appear in person at full parole board hearings. She said she wanted to do something for victims’ rights, something to honor the memory of her daughter, Melissa Anne, 19.

“You never know what it’s like until you’re faced with the situation, and I just wonder if these people on the parole board — they don’t have any idea what it’s like to have a family member murdered,” she said. “I just felt very strongly that my husband and I need to be present to express exactly how we felt, and hopefully it would make a difference to the people on the parole board.”

Miss Herstrum was a nursing student at the University of Toledo in 1992 when then-UT Police Officer Jeffrey Hodge abducted her, shot her 14 times, and left her dead in the snow on UT’s Scott Park campus.

The Rev. David Bell of Rocky River United Methodist Church, left, escorts Diane and Alan Herstrum from the church after the funeral for their daughter Melissa Anne Herstrum.

It was a crime that stunned the community and still leaves the young woman’s mother incredulous.

“Murder was the farthest thing from my mind when I sent our daughter off to college,” Mrs. Herstrum said. “What are the chances you send your daughter off to college and she’s murdered by the campus police officer?”

Hodge was convicted and sentenced to life in prison and eligible for parole after 33 years. He was sentenced before life without parole was possible in Ohio.

Twenty years after Hodge saved himself from the death penalty by pleading guilty to aggravated murder, kidnapping, and the use of a handgun in the commission of a felony, the rights of victims to be involved in and better informed of parole hearings has increased considerably.

On March 22, a new measure dubbed Roberta’s Law went into effect in Ohio that requires the Adult Parole Authority to automatically notify victims or victims’ survivors when an offender convicted of aggravated murder, murder, or other violent felonies is up for parole, judicial release, or pardon.

Those who do not want to be notified may opt out.

“This is a good law,” Mrs. Herstrum said. “This is a very good law.”

Roberta’s Law

In the past, victims or their family members had to register with the state for such notification. Many, like Robert Francis of Columbus, never knew that.

Mr. Francis’ 15-year-old daughter Roberta, for whom the law was named, was raped and beaten to death on her way home from school in 1974. He learned in a newspaper article that his daughter’s killer had been released from prison.

ROBERTA'S LAW

Senate Bill 160, dubbed “Roberta’s Law,” requires the state to automatically notify victims or their surviving family members when an inmate convicted of aggravated murder, murder, or a violent first, second, or third-degree felony, or an inmate serving a life sentence is up for release or transfer proceedings.

The Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction is asking all affected victims to contact the Office of Victim Services by calling 1-888-842-8464 or by sending an email to drc.victim.services@odrc.state.oh.us to either provide information regarding their preferred method of notification or to opt out of notification.

Bret Vinocur, a victim’s advocate who helped write Roberta’s Law, said Mr. Francis didn’t understand why he hadn’t been contacted about the offender’s parole hearing; he’d even lived in the same house for 40 years and was not hard to find.

“Mr. Francis is in his 80s. He doesn’t use the Internet,” Mr. Vinocur said. “People like him have no idea to go on the [Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction] Web site. They would never think, ‘I’m going to call ODRC and sign up for victim notifications.’ They don’t even know it exists.”

Mr. Vinocur worked with Sen. Kevin Bacon (R., Minerva Park) to get the bill introduced and ultimately passed and signed into law by Gov. John Kasich. He said he believes it will have “great impact and minimal financial impact.”

“I cannot imagine another state having a victim’s rights law on the books that is better than Ohio,” Mr. Vinocur said. “This finally gives the victims fairness in the process.”

Leslie Robinson of Toledo, whose only son, Dionious, was shot to death in 2005, said too often, family members are too drained by the ordeal of court proceedings after a loved one is killed to think about signing up for parole notifications.

“I give it two thumbs up because unless people are told this is available to you, a lot of them walk away thinking, that’s it. It’s over. Then they walk past [the killer] one day on the streets and think, ‘It seems like I should’ve been notified,’ ” Mr. Robinson said.

Notifying victims

The Adult Parole Authority now is identifying and notifying victims in the cases of inmates who are up for parole in the next six to 12 months, said Cynthia Mausser, chairman of the parole board.

It’s a daunting task. Ohio has approximately 4,800 inmates like Jeffrey Hodge who were incarcerated before 1996 when Ohio began giving definite sentences. An additional 3,200 were sentenced to life with the possibility of parole under current law, and some 25,000 others are incarcerated for violent first, second, and third-degree felonies whose victims also are covered by Roberta’s Law.

In addition to doing its own searches for victims, the parole authority is asking victims or their surviving family members to contact its Office of Victim Services by phone or email to provide it with contact information.

Ms. Mausser said board members want to hear the victim’s side and thoughts when deciding whether to release an offender, though she couldn’t say how much that affects the board’s decisions.

Public safety is the overriding concern for the board, although it also considers an offender’s current and past patterns of offense behavior as well as psychological and psychiatric evaluations of the offender.

“It’s hard to say how much weight we give to any particular factor, but ultimately the more information the board has from all interested parties, the better our decisions are,” Ms. Mausser said. “I think it makes a difference in that if we don’t have that piece of information, [then] we’re making a decision on information that’s absent. Yes, there are times when [a victim’s family statement] results in the person not being released, coupled with other factors.”

Under longstanding policy of the board, a victim’s representative can request a briefing before an inmate has his or her institutional parole hearing, which is not an open hearing. The victim’s representative, such as a family member, as well as judges, enforcement officers, and prosecutors who were involved in the case, can request a full hearing of the board that he or she would have the right to attend.

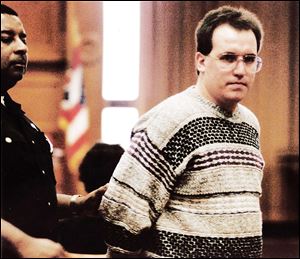

Jeffrey Hodge, a former University of Toledo police officer, was convicted in the 1992 slaying of Melissa Herstrum. He could be eligible for parole in 2022.

Ms. Mausser declined to speculate on whether Hodge, or any particular inmate, is likely to qualify for parole over the life of their sentence, but noted the board’s annual release rate is between 13 and 18 percent.

‘Life imprisonment’

According to the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction, Hodge — who does not come up for parole until 2022 — has been busy in his 20 years behind bars.

Held at the Marion Correctional Institution where he is classified as an “electronics tech” in the chaplain’s area, Hodge declined an interview request from The Blade, as he has in the past. ODRC Spokesman Mike Davis said Hodge sets up microphones and other equipment and plays recorded music for religious services.

He plays the keyboard in the chapel band that performs at services and special events and participates in “prayer and share” activities. Mr. Davis said Hodge assists with the prison’s three-day, Christian retreat known as Kairos and with a six-month mentoring program for younger offenders.

Mr. Davis said Hodge recently completed a victim-awareness program designed to help offenders understand the impact crime has on victims.

None of that matters to Lucas County Prosecutor Julia Bates. She said she has no doubt Hodge is a model prisoner, but like Miss Herstrum’s family, she said she will oppose his parole “for as long as I have breath in my body and work here.”

“You can be as good as gold in prison because you’re not outside,” Mrs. Bates said. “This was a brutal, unnecessary, vicious, wicked deed, and life imprisonment to me is life imprisonment.”

The fact that Hodge, who was just 22 when he killed Miss Herstrum, was a police officer in a position of trust exacerbated the crime, she said.

The decision to cut a plea deal with Hodge was controversial at the time, with soon-to-retire Prosecutor Anthony “Tony” Pizza making the deal and then-Common Pleas Court Judge Judith Lanzinger agreeing to it, saying at the time that she thought the plea agreement was reasonable. She said that a conviction and death penalty weren’t impossible to gain, but that the certainty of a lengthy prison sentence was better in the eyes of the prosecutor than the many potential problems of a case based largely on circumstantial evidence at trial and on appeal.

“It’s very, very easy to say there should be the death penalty in every murder case,” Judge Lanzinger said.

She added that the presumption of innocence stays with a defendant and problems of evidence of must be considered.

In October, 1994, as Judge Lanzinger sought re-election, she said during a televised exchange with her opponent, J. James Bishop, that a jury could have acquitted Hodge. She said that Mr. Pizza recommended the plea agreement because the evidence was purely circumstantial, and that the prosecutor had to prove Hodge was guilty of murder and kidnapping in order to get the death penalty.

“We had no confession; there were no admissions,” Judge Lanzinger said in 1994. “It was risky going to trial.”

In the courtroom on the day the judge assented to the plea deal, after Herstrum family members had delivered emotional accounts of their loss, Judge Lanzinger told Hodge that what he had heard “were cries from the heart. I want you to hear those cries for the rest of your life. I hope you never forget that day.”

In addition to the family and prosecutor’s office, the University of Toledo also would be in line to oppose release for Hodge. In December, 1997, UT agreed to pay $1 million to the Herstrum family to end a $10 million negligence lawsuit stemming from her murder.

UT also agreed to join the Herstrum family in opposing any attempt by Miss Herstrum’s killer to gain early release through parole.

As for Roberta’s Law, Mrs. Bates said it should be good for victims of all violent crimes, sadly because there are so many.

“We don’t want people to fall through the cracks. We want victims to have the opportunity to know if they want to object [to parole] because the continuity of prosecutors — even though I’ve been here a long time, I don’t know every case that ever happened going back to the ’70s,” Mrs. Bates said. “There is so much turnover, but the victim is still the victim, and if the victim is still available or somewhere that they can be contacted, that is very, very important.”

The opposition

Not all victim advocates supported the new law.

David Voth, executive director of Crime Victim Services in Lima, Ohio, and policy chairman of the Ohio Victim Witness Association, said he fears the law will hurt some victims who simply don’t want to be reminded of what they went through.

“Many victims do not want to be found,” he said. “They want no part of this and the fact that the state can find you means the perpetrator probably can find you.”

Roberta’s Law does include an “opt out” provision, meaning any victims who do not want to be notified may choose to not be notified.

“I certainly see the value of this law. Even though I’m opposed to it, there are going to be some victims who are helped,” Mr. Voth said. “I think in a year or two we’re going to have to have a heart-to-heart with each other and determine how many victims did you find who are just so mad now [that] they’re back in counseling, and how many were just so grateful.”

Mrs. Herstrum said she, her husband, Alan, and their older daughter, Cindy, are committed to fighting Melissa’s killer’s parole as long as necessary. She believes Hodge should die in prison.

“I feel pretty strongly that if someone takes another person’s life, they really don’t deserve to live. Certainly they should remain in prison to continue living,” she said. “That wasn’t a possibility in our case. When Melissa was murdered, there wasn’t life without parole.

“As our detective said, [Hodge] needs to stay in prison until he’s dead, and that’s my exact feeling,” she said.

Staff writer Tom Troy contributed to this report.

Contact Jennifer Feehan at: jfeehan@theblade.com or 419-213-2134.