An elevated art form

10/6/2001

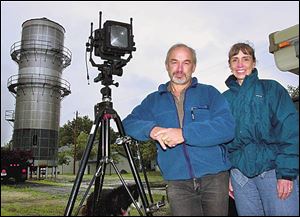

Bruce Selyem and his wife, Barbara, arrived in Elmore only to find the grain elevator he sought had been torn down.

Bruce Selyem is a photographer obsessed with country grain elevators.

He's shot nearly 50,000 pictures of wood grain elevators and invested $100,000 in film and processing. See more grain elevator photos

His mailbox, doghouse, weathervane, and garden shed have grain elevator themes and every room of his house in Bozeman, Mont., is wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling, elevator memorabilia - a decorating scheme his wife, Barbara, calls “tastefully bizarre.”

Even their wedding rings are engraved with grain elevators. The couple met at a program Mr. Selyem presented on grain elevators.

“They're just clearly nuts about grain elevators,” said Thomas Lee, a photographer at the Bozeman Daily Chronicle.

This year Mr. Selyem, who was born in Cleveland and lived in nearby North Royalton until he was 8, returned to Ohio to photograph grain elevators.

He shot 39 elevators in northwest Ohio, his easternmost stops on a three-week trip from Montana during which he shot 200 elevators. One of his favorites was an elevator he found in Woodville, painted green, on a day that the sunlight was to his liking.

Another favorite was in Deunquat, a tiny dot on the map in northeastern Wyandot County where the Selyems happened upon an elevator that they didn't expect.

He's come to regard wooden grain elevators as monuments, rising up from the rural landscape, “like mountains to me on the prairie,” and finding one by surprise seems like a gift.

Grain elevators are unique to the rural landscape and Mr. Selyem realizes most Americans probably don't recognize the uniquely shaped structures as buildings to store grain. His mission is to change that and he hopes to make the wooden grain elevator an icon of the Midwest, much like lighthouses are to the Great Lakes.

That love of wooden elevators built in days gone by - today elevators tend to be far larger and made of concrete - has helped him shoot remarkably different images of buildings that are much the same.

“They're really good pictures,” Mr. Lee said. “He shot them all with good light, he varied his compositions, he varied his point of view.”

During the 15 to 20 minutes that Mr. Selyem spends photographing an elevator, his wife looks for people who can tell her something, almost anything, about the elevator.

When he's shooting an abandoned elevator, she knocks on the door of a nearby house - usually choosing the one with the nicest lawn and garden, a clue she says helps her find long-time residents. And if she doesn't have any luck on the road, she mails a letter addressed to “Whoever knows about the elevator” in care of the local post office.

She realizes the elevator history provided to her through such means isn't error-free. For starters, her sources often disagree and she doesn't triple check every fact she gleans about the thousands of elevators her husband shoots.

But she's looking more for stories about life at the grain elevators than names and dates.

Her favorite was told by an older man in Montana after one of Mr. Selyem's slide shows.

The man said when he was hauling grain to elevators, women were just beginning to drive grain trucks.

In the elevator, there was a clerk who - unbeknownst to the women drivers - was weighing their trucks as soon as they pulled on the scales. He would then measure the weight again when they had jumped out of the truck to come into the office and quietly calculate the difference between the two figures. That gave him the weight of each woman driver - which he marked on a chart kept strictly for the entertainment of him and his colleagues.

When Mrs. Selyem tells that story, she can pick out women in her audience who have hauled grain to an elevator. They fall dead silent. There's a look of horror in their eyes. And their thoughts are plainly: “What if someone did that to me!”

Mr. Selyem's favorite story comes from another Montana program when he asked the audience to share grain elevator memories.

A tiny woman who appeared to be near 90 told about growing up when mothers made their daughters' clothing out of the cotton sacks that elevators filled with livestock feed.

By chance, a pair of her underpants were cut so that the words “Montana's best” from the sack label appeared right across her backside. The printing wouldn't come out with lye or bleach.

Amusing as such stories are, the 40 hours a week that Mr. and Mrs. Selyem each spend compiling the history and shooting pictures of country grain elevators is less than lucrative.

Mr. Selyem sells prints, starting at $132 for an 11-by-14 up to $308 for a 30-by-40.

Buyers tend to be people who are employed or closely tied to the grain industry, such as Don Wiseman, general manager of Sunray Co-Op, Inc., in the northern panhandle of Texas.

“I think it's pretty good photography,” he said. “But the other thing that simply interested me about it is for 35 years I've been in this business and I like the old facilities, the heritage.”

Galleries sometimes pay for shows of Mr. Selyem's work. However, he will display his photos for free if he doesn't have another place for them at the time. He collects speaker's fees for his slide shows and the Selyems put together a regular column and pictures for Grain Journal, a trade magazine.

“I like it because it's something different than what we normally do and the pictures are good,” publisher Mark Avery said of the column that is often the only folksy offering in the technical publication.

But it's Mr. Selyem's part-time job at the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman that makes the house payments and free-lance photography jobs that pay the other bills.

On trips to take pictures of grain elevators, the Selyems limit themselves to $60 a day for gasoline, food, and lodging. They camp whenever practical. They budget $100 for every day on the road for film and processing.

Mr. Selyem shoots each elevator in three formats: 35 millimeter, medium format, and 4-by-5. The cost for film and processing of color, 4-by-5, is about $5 for every click of the shutter.

The Selyems have grain elevator dreams, however, that are far taller than taking pictures. They hope to buy a grain elevator near Bozeman and convert it into a museum that would tell about the 27,000 licensed grain elevators that dotted the United States in the 1920s and '30s. Less than half that number remain today, Mr. Selyem said.

How feasible opening such a museum would be is uncertain, however, even to board members of the Selyem's Country Grain Elevator Historical Society, which charges $20 for annual memberships.

Marjorie Smith, a fiction writer who is on the board, said raising what would almost certainly be millions of dollars to transform an old elevator into a child-safe, handicapped-accessible museum will be difficult.

However, Mrs. Selyem, who once worked in the grain industry, appears to have utter confidence that the museum will become a reality.

And Mrs. Smith says Mrs. Selyem might have the charm and contacts to pull it off.

“I wouldn't want to question Barbara when she says we'll find the money. So far she has,” Mrs. Smith said.

To share a story about an old wood country grain elevator with the Selyems, write to them at bselyem@grainelevatorphotos.com or 155 Prospector Trail, Bozeman, MT, 59718.