Teen cliques

3/23/2003

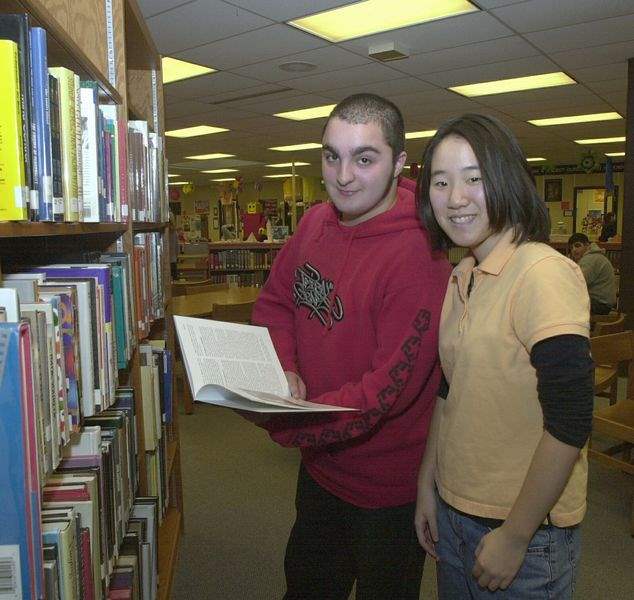

Sammy Kahaly, 16, and Judy Ch'ang, 16, students at Southview High School, say it is natural for people to form social groups.

Melissa Rozic is a senior at Anthony Wayne High School.

Anthony Wayne High School senior Melissa Rozic, 17, was tormented in school two years ago by two boys who called her “fish.”

“Every day they made fun of me. It hurt me. I would go home and cry,” she says.

Mitch McVicker, a 17-year-old Anthony Wayne junior, recalls when his circle of close friends was fractured by a nasty prank, leaving Mitch painfully in the middle - still friendly with all the feuding parties, each side resenting his continued contact with the other. “I could never have a party,” he says.

Melissa and Mitch say those problems have been resolved, and that high school is a pretty nice place now. Social groups exist, and some kids are more popular than others, but all in all everyone gets along pretty well, they say.

Other students aren't so fortunate.

“I think most people want to believe that things are better,” says Kelvin Datcher, outreach coordinator of the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Ala. “Unfortunately, we still see that young people believe they are locked into and out of all kinds of groups in their schools.”

In an effort to measure the extent and impact of cliques, the center is in the process of compiling thousands of surveys from students and adults across the country. In the meantime, Mr. Datcher declares, “the consequences of cliques are certainly greater than they ever have been.”

High-profile cases of school violence - such as the 1999 shootings at Columbine High School in Colorado - have been linked to cliques. News accounts cited the hostility among the school's social groups, and the ridicule that drove outcasts Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold to lash out. “This is for all the people who made fun of us all these years,” they reportedly said as they opened fire.

Libbey High School Principal Howard Brown says he thinks the nature of cliques has changed since he grad

uated from high school in 1966. Back then, he says, members seemed to challenge each other to do better; there was healthy competition. “Now, I see just the opposite,” he says. “They work down to the lowest person sometimes.”

Students who are capable of getting good grades, for example, won't make the effort in order to stay in favor with popular under-achievers.

Yet, although teasing among students persists, “We haven't really seen any problems between groups,” Mr. Brown says.

Sammy Kahaly, 16, a sophomore at Sylvania Southview High School, points out that social groups aren't inherently bad. “Groups become bad when people are ostracized.”

And, notes Judy Ch'ang, 16, a junior at Southview, adults also form social circles. “It is human nature.”

“If you don't like someone, it's not because of the group they're in,” says Melissa Masters, 17, a junior at Central Catholic High School.

“It's their attitude,” adds her friend, Ashley Miller, 17, also a junior at Central Catholic.

Local students describe a social system of porous, overlapping groups based on common interests, activities, or dress. Names, groups, and characteristics may vary somewhat from school to school, but the assortment includes the academic standouts (“the smart kids”); the athletes (both girls and boys); “party-ers” or “potheads” (alcohol and drug users); “Goths” (spiked jewelry, body piercing, unnaturally dyed hair, “weird clothes”); “preppies” (stylishly long hair, outdoorsy and classic clothing); “ghetto people” (street slang, oversized clothing, “hoodie” sweatshirts, baseball caps cocked to the side, fans of hip hop and rap), and “skaters” (baggy pants, hemp jewelry, hair washed with soap “so it's kind of grungy looking.”)

People can be “geeky” - think bulging book bags and pants that graze the top of the ankle - but “we don't classify anyone as `geeks,'” Ashley says.

Nor are students categorized based on race or income, Melissa Masters states.

All the students who were interviewed see themselves as spanning numerous categories.

“I'm an athlete, but I dress preppy and I listen to rap,” Ashley says.

“I play football, but I also get good grades and debate,” Sammy says.

At Anthony Wayne, Melissa Rozic says that, “I have a certain group of friends, but I'll hang out with anyone I can relate to.”

Sammy Kahaly, 16, and Judy Ch'ang, 16, students at Southview High School, say it is natural for people to form social groups.

Psychologist Lawrence Moyer says that pre-teens and adolescents look for social groups to help them form an identity outside the family.

Those early peer connections - or lack of them - can have lasting effects. Someone who can't fit in anywhere may grow up with low self-esteem and a perception of being a victim, says Dr. Moyer, who is clinical therapy supervisor of the partial hospitalization program for elementary school-aged children at the Kobacker Center, the Medical College of Ohio's child and adolescent psychiatric unit.

But developmental paralysis also can happen to someone who lands a spot in an elite social group. On a pretty harmless level, it might be a middle-aged man who wears the same hairstyle as he did when he was the high school hunk. It's a process that Dr. Moyer calls “arguing for our limitations. You stop seeing yourself as open to growth or change.”

Dr. Moyer says he has worked with young people who have changed schools because of painful social situations. One young girl fled because she was teased about being overweight. “Over time, it got to be unbearable for her,” he recalls. “She didn't know how to defend herself. She was very insecure. We got her into another school, and she did much better, but the scars are always going to be there.”

Young people often don't understand how painful their words and actions can be, says Lisa Ernsthausen, a business technology teacher at Anthony Wayne. “They don't think about how they felt when something hurtful was done to them.”

Mrs. Ernsthausen is the school coordinator of Anthony Wayne's Youth Challenge Program, based on the Challenge Day experience that has been offered by Anthony Wayne, Sylvania, Toledo's Start High School, and some other area schools. Started in 1987 by a California couple, it involves a series of exercises to help students understand that other people wrestle with the same problems and feelings that they do.

In one, everyone lines up and is asked to step forward if they can say “yes” to questions such as, “Have you ever been physically or sexually abused?” and “Have you ever thought about committing suicide?” In another, they have a chance to talk about how they've been hurt, to make apologies, and to talk about feelings.

“All of a sudden, [students realize that] Little Susie Cheerleader who seems to have the perfect life really doesn't,” says Amy Clark, community volunteer for the Anthony Wayne Challenge program.

“I think kids talk and get vulnerable with people they never would have talked to before,” adds Mrs. Clark, who discovered the Challenge Day program and brought it to Anthony Wayne. She is the mother of Mitch McVicker, the teen who had found himself in the crossfire of angry friends. The experience “stresses getting out of our comfort zone,” Mitch explains. “Everybody wants to be comfortable - that's why there are cliques. Challenge Day gives you the tools to communicate with others, and you have to make the choice.”

Katharine Heintschel, assistant principal at Anthony Wayne, says disciplinary referrals have dropped. “The number of students we suspend for fighting or harassment has gone down significantly since we started the program. ... What Challenge Day does is to give students who are wanting to resolve conflict in a positive way some skills to do that.”

Southview Principal Jeff Kurtz says it's too early to measure the effect of Challenge Day there. “Overall, I think our kids are sensitive, but there is always room for improvement.”

The goal of another nationwide initiative undertaken last fall was beautifully simple: just sit with someone different at lunch. Called “Mix It Up At Lunch Day,” it was co-sponsored by the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Study Circles Resource Center of Pomfret, Conn., which promotes group problem-solving on social and political issues.

“Our goal was 500 schools when we created the program last summer,” says Mr. Datcher of the Southern Poverty Law Center. An estimated 200,000 students at more than 3,000 schools participated, he says, adding that he doesn't know how many in northwest Ohio and southeast Michigan may have been among them.

“We were kind of overwhelmed with the response we got,” Mr. Datcher says, noting that both students and teachers crossed racial and social boundaries in school cafeterias. The success of the project on Nov. 21 has spawned a broader campaign of organized student discussions this spring.

“We realized that young people tend to sit with people like them every day, and it's a tradition built more out of repetition than malice, but it tends to reinforce barriers between young people,” Mr. Datcher observes. Those barriers can give young people a sense of isolation and intimidation in their school, he says, and give rise to bullying, teasing, even violence.

“ `Kids will be kids' is what we used to say about some of these issues,” he adds, “but we're learning that we have to intervene and support our young people. `Kids will be kids' is not acceptable.”