Many of Ohio's older burial grounds have devilishly intriguing titles

10/24/2007

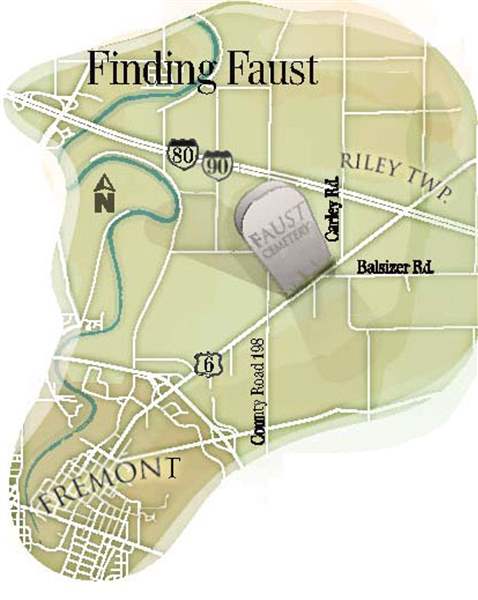

The entrance to Faust Cemetery near Fremont.

RILEY TOWNSHIP, Ohio - The cornstalk genuflects and nods and twists and finally, losing its struggle with the autumn wind, snaps off above its base. It sails across the two lanes of U.S. 6, catches an updraft, and tumbles in midair. Trucks hauling mountains of pumpkins rumble past. The stalk gets kicked higher. It hovers for a moment and the wind dies. Safely on the other side of this slim country road, it glides down and comes to rest in a cemetery.

The grass, green and thick.

As you glance across the corn and soybean fields surrounding this small graveyard, you realize it's the only place for a half-mile around where land has any inclination at all, a slight rise at that. Whomever built this cemetery knew where to dig, says Dan Polter. He owns a berry farm up the road. "It's good ground," he says.

And it is.

The oldest headstones - that is, the oldest not yet grown illegible from 150 years of weathering - date back to circa 1840 and still stand upright, if a bit jagged and tilted now, oxidized and bone white from age, like a mouth with haphazard rows of crooked teeth. It's a place of first names like Wilhelmina and Zerah and a few Marthas. Store-bought wreaths of plastic leaves and pumpkins and acorns adorn graves here and there, and against one tombstone a blue Ladies Auxiliary flag flutters, worn thin, shredded by the wind. The cemetery is not crowded. There are 70-odd plots, and of the four graveyards in this town of 1,300, a corner of Sandusky County which bumps against Fremont to the southwest, it's the busiest.

A view of gravestones in Faust Cemetery.

Nothing unusual about it.

A quaint, picturesque spot.

Oh, wait.

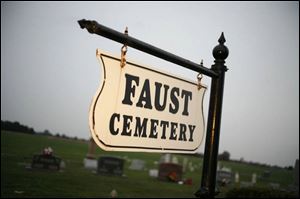

It's called Faust Cemetery.

Tooling down U.S. 6 you do a double-take - did that just say Faust, er... Cemetery? Faust, as in the legend of Faust? As in the centuries-old German folktale of the man who sold his soul to the devil? As in the basis of nearly every story of anyone who ever made a deal with the devil, from Thomas Mann's Dr. Faustus to Marvel Comic's Ghost Rider? As in, Man, is it me or is that a really creepy name for a cemetery?

You stop the car.

Yup. Says it in black and white, right on the sign, which suddenly you notice creaks in the wind, which suddenly you notice whistles, which suddenly you notice brings with it a gathering army of storm clouds, which seem to blot out the very sun and, uh -

"Actually, it's named for a family, the Faust family," says Joseph Halbeisan, the township clerk, who just happens to have lived across the street from the cemetery all his life. "There is nothing spooky about this place." Of course, he's right. His parents are buried there. And one day, he will be, too. His home happens to have been built by the Fausts. There are none left in Riley, he says. The name is a remnant of the German and Scandinavian immigrants who settled in rural Ohio during the 19th century; indeed, there are 17 Fausts listed in the Toledo phone book.

And it's also a reminder that cemeteries become a part of their communities, as families and names and landmarks do, and their names get taken for granted - we hear people say those names, we see the signs, but we no longer hear them, and no longer see them. Which itself is a window into how cemetery culture has changed since Faust Cemetery was founded in 1833.

According to the Ohio Genealogical Society, which four years ago published a list of every Ohio cemetery it knew of, there are 14,600 cemeteries in the state, both active and inactive. The Ohio Historical Society says it doesn't even know all of the cemeteries in Ohio, and that such a list is elusive, since many have never been registered and many more are so small they were forgotten. There are competing directories of Ohio cemeteries, both online and in print, from hobbyist and organizations, and each has its omissions and exclusives. But between them, that name, Faust Cemetery - it's almost ordinary.

Because it's not Sodom.

That's in Champaign County.

Sodom Cemetery, that is.

Not to be confused with Sodom Cemetery in Miami County.

There's also a Hell Cemetery.

Or, as with many cemeteries, there was. Hell Cemetery was in Preble County, in the southwest corner of the state. It existed until 1860 - until someone built a house on Hell. Though, if you must be buried in Hell, you have options - Hell's Half Acre Cemetery is in Lebanon Township. And according to Katie Karrick, a Cleveland cemetery aficionado, who leads a popular walking tour of graveyards and lectures on cemetery appreciation at a number of Ohio colleges and museums (and keeps a Web site called "A Tomb With a View"), over the years, she's counted 97 different Ohio cemeteries with a variation on the name "Salem."

Read on, there are more.

But Faust - pretty tame.

Walking through the cemetery, Mr. Halbeisan notes that most of the graves are pointed west instead of the more traditional east. So that's unusual, perhaps. And back against the north side of the plot, which looks out on the Ohio Turnpike in the distance, there are the half-dozen or so Fausts actually buried here, the most recent in 1910; John Faust - the first of the Riley Fausts, according to local historian Joan Jahns - has a headstone a full head taller than his wife's stone. But there's nothing here that associates with the Faustian legend, Mr. Halbeisan says.

The name, it ever bug you?

"You'd have to ask Mr. Faust."

He squints into the wind.

"I didn't make any deal."

In 1826, the Faust family came to Riley from Pennsylvania, according to Jahns, who compiled an exhaustive history of her town for the Sandusky County Kin Hunters, the local genealogical society. The Fausts did what immigrants did when they could - they bought land, and in 1833 they deeded a small plot to Riley for $2. It was used for a schoolhouse, but "in the day, the local school board was responsible for the local cemeteries, too," she said. When the school moved, the cemetery remained.

The surname would have been common at the time, said Geoffrey Howes, a professor of German at Bowling Green State University. "It just means 'fist,' and there's no real evidence of an association between the family name and any literary figure."

The thing is, even if there had been a connection, even if the Faust surname had been taken as a perverse tribute to the infamous legend, it might have still shown up as a cemetery name.

"Americans were probably a little more blunt in their dealings with death at the time," said Gary Laderman, author of The Sacred Remains: American Attitudes Toward Death and a professor of American Religious History at Emory University in Atlanta. Severe, even puritanical, attitudes toward cemeteries and what they meant were not unusual. "There was more candor in the 19th century when there was more death," he said, "when people didn't live as long or died quicker when they got sick. As we moved into the 20th century and life expectancies increased, death became less personal and people didn't see it themselves."

The cemetery softened.

Beth Santore, 28, a Columbus software tester and trustee with the Massachusetts-based Association of Graveyard Studies - her Web site is called "Grave Addiction" - remembers bending down to get a better look at a tombstone in Wyandot and being startled. "The carving was very weathered, but if you looked close you could see the picture of a small boy being thrown from his horse. I mean, that's pretty harsh." Indeed, Mr. Laderman said, you're less likely to see any cause of death on a headstone today, less religious iconography, too.

If anything, trying to find a cemetery today, you might confuse the names with suburban subdivisions - Riverside, Oakwood, Highland, Franklin, etc. Among the largest cemeteries in Ohio are Lake View in Cleveland and Spring Grove in Cincinnati.

Ms. Karrick, of A Tomb With a View, said if you walk through enough Ohio cemeteries you will notice the evolution of our ideals. "Older stones might say 'Going home,' while I've seen one stone reading 'Gone to Wal-Mart.' You just don't see the glorification of death now that you do in a Civil War or turn-of-the-century headstone."

In fact, in Ohio alone, if you're looking for spooky old cemetery names, according to Ms. Karrick, there are four Hitchcock cemeteries and fives Bates cemeteries - "as in Norman, if you're inclined." There is a Poe Cemetery. There are four Gore cemeteries, and there is one Borden - "like Lizzie, if you want." There are three Bones cemeteries as well.

And two Shock cemeteries.

Say you want to do an interpretative walking tour of slasher film history: There is an Axe Factory Cemetery near Norwalk and a Student Burying Ground Cemetery in Butler County (seriously). And a Coffin Cemetery.

Brimstone Corner Cemetery.

Shingletown Ghost Cemetery.

Dead Man's Point Cemetery.

Devil's Half Acre Cemetery.

There's a Spooky Hollow Cemetery outside Cincinnati, and a Slab Hollow Cemetery in Jackson County, and, eeriest of all, Hocking County once played host to a Shades of Death Cemetery. Oh, and there's a Devil's Den Cemetery near Columbus. Not a single one, almost certainly, was established in the past 100 years. And most are difficult to locate.

But not Faust Cemetery.

It's right there, at the side of U.S. 6. Almost no one who sees it everyday links it back to the legend - probably no one at all. Understandably. Even in Medina, where there is a River Styx Cemetery, Bonnie Lach, of the Friends of the Cemetery advocacy group, connects the name to a local road named River Styx.

"It's a name, and that's all."

But for men, a Faustian Bargain will always be about power, said Inez Hedges, who teaches German at Northeastern University in Boston and wrote Framing Faust: 20the Century Cultural Struggles. For women, she said, it's about beauty; for the German writer Goethe, whose own Faust is the most revered, unlimited knowledge is the price of a man's soul. "The legend will never die because it's a Western thing, and there is so much we can't have."

For Joan Jahns, who already owns a gravestone in the Faust cemetery with her name on it, Faust will mean home. "The scariest thing about it, I think, is the possibility someday they'll widen Route 6."

Contact Christopher Borrelli at: cborrelli@theblade.com

or 419-724-6117.