A fair share; how to divide an estate without splitting the family

7/6/2008

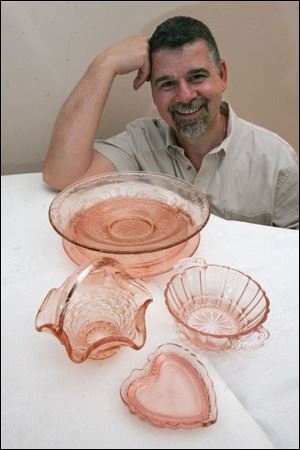

Michael Catanzaro with a few pieces of his mother's pink Depression glassware that he inherited in 2007.

The Blade/Lori King

Buy This Image

Judy Conibear, left, and her sister, Karen Bracken, with special jewelry that once belonged to their mother.

Sharing was a way of life for the 12 children of Nick and Betty Catanzaro.

And so it was after their parents died Nick in 1994, Betty last June.

On her final day, my Mom said she knew nobody would fight [over her estate], says Michael Catanzaro, of Sylvania, one of their six sons. When she said something, that was the law, and we took it very much to heart.

From her old gravy spoon and white glass mixing bowl to her diamond jewelry and collection of Hummels, everything was divided without arguments, complaints, or tears, he says.

When it came down to these final possessions of my mother s, it wasn t a matter of, I want that. It was, Gee, I would really like to have that. Is anyone else interested in it?

We were overjoyed for whomever, for whatever they got, he adds.

Sadly, that s not always the case.

It s been almost four years and our family still doesn t speak; probably never will, an anonymous reader said via e-mail after The Blade asked families to share the ways in which they had kept the peace through the emotionally charged task of settling an estate.

Linda Mansour, a Toledo attorney and mediator, says she once worked with a family who fought over the ashes of their deceased relative. I had the ashes in my office for years, she says.

And Jamie Thompson, owner of Wildwood Antiques Center & Auction Gallery in Holland, marvels at the ugliness he has seen while handling estate liquidations and settlements.

Unfortunately, what happens is emotion gets tied in with greed, Mr. Thompson says. I ve seen fist fights between brothers. ... Family members break things so another family member can t have them. They hide them, they steal them. ... It s amazing the emotions that come from nowhere when it s time to get rid of the stuff.

Author Julie Hall writes in her new book The Boomer Burden: Dealing With Your Parents Lifetime Accumulation of Stuff (Thomas Nelson, $14.99) that Grief can bring out the best or the worst in us, and your response to the first disputed object will set the tone for the rest of the process.

She suggests you ask yourself this: What s more important, having your father s stamp collection or honoring your parents memory by doing everything you can to keep the peace?

Even close-knit families can be pulled apart if childhood jealousy, resentment, and hurt feelings resurface during the process of dividing the estate, adds Mrs. Hall in a telephone interview from Charlotte, N.C. My message to people is, why would you fight over an object that you can t take with you, either?

Wally Igielski of Sylvania says that he and his brothers split their parents estate 13 years ago without an argument. Working together to clear out the house and get it ready to sell brought them even closer than they had been before.

They agreed to reduce the number of people making decisions by leaving their wives out of it. Then, if more than one brother wanted the same thing, they d draw cards. High card won, and that was that.

I lost most of the drawings, he remembers with a chuckle.

Bev Rutter of Bowling Green says she and her siblings also agreed to leave the family members they affectionately call the outlaws behind while they cleared out their mother s mobile home. The only exception was their brother s widow.

One room at a time, they took turns selecting items, starting with the youngest person and going in order to the oldest. In the next room, the order of selection switched from oldest sibling to youngest.

That worked beautifully, Mrs. Rutter says. No one was getting more than the other, and you could see that.

Taking turns also worked for Judy Conibear of Bowling Green and her sister, Karen Bracken of Ann Arbor, when they divided the jewelry of their mother, Ethel Pendleton.

I was nervous going into the whole situation, Mrs. Conibear admits. Afterward, she worried that maybe she got more than her sister did, so she asked her: Was there anything you wanted and didn t get? She said no, she was happy with what she got, Mrs. Conibear says.

When the sisters had taken what they wanted, they invited their children to come to the house, and without conferring with one another to walk around, make a list of things they wanted, and then prioritize them. The selection process started with the oldest grandchild and worked down.

There were one or two times when they both wanted the same thing, but they nicely deferred to each other, Mrs. Conibear says.

I was so grateful, because I had heard some horror tales, and I was very unhappy about my grandmother s estate. There were things I would have cherished but my aunt said everything was going to be sold.

Twila Zimmerman of Graytown, Ohio, and her brothers drew numbers to decide who would go first, second, third, and fourth for the opening round of choosing items in their parents estate. After the first round, the No. 2 person moved up to No. 1, and so on. Everything had been appraised, but dollar value wasn t a consideration, she says.

We had no problems at all, Mrs. Zimmerman says. If you give a little bit, it works out.

The 12 Catanzaro heirs held a blind drawing for many items. They made 12 packages of jewelry of similar value, tagged paintings with numbers 1 through 12, and bundled

12 sets of Hummels, for example. Names were put in one basket, and numbers in another. After the drawings, everyone was free to swap, which they did, Mr. Catanzaro says.

Mrs. Hall, the Boomer Burden author, says that one of the most important ways to head off disputes among heirs is for parents to make decisions in advance about who gets what.

Handle this while you re still alive, she says. Ask the kids what they d like to have, and give them those things or tag the objects for them to receive later on.

Michael Catanzaro with a few pieces of his mother's pink Depression glassware that he inherited in 2007.

If your children already are clashing over the same item, make the decision for them, she advises. There may be some hard feelings at the time. But if you leave it for them to decide after you re gone, the ensuing battle could damage their relationship forever, Mrs. Hall points out.

Probably 80 percent of my estates end up in squabbles, Mrs. Hall says. Those are the ones where the parents did not offer any guidance to the children whatsoever.

Reynolds Corners residents William and Mary Rumbaugh asked their children about six years ago to put in writing what they d like to have. For many objects, there was no duplication on the lists, and where there was, they worked out a solution.

The couple also set up a living trust and took other legal steps such as naming family members to handle financial and health care decisions if they become incapacitated.

Mr. Rumbaugh says they decided to act after seeing family feuding that erupted over the estate of someone they knew. I didn t want that to happen, he says. We sat down and talked to everyone individually after they decided what they wanted and to make sure everyone was OK.

He says he believes the entire family is comforted by what he and his wife have done. The parents have peace of mind; their children realize that our death is not going to tear the family apart. They re still going to be friends and talk to each other, and know that the things they really value, they got.

Mrs. Hall and Mr. Thompson, both appraisers, stress the importance of hiring a professional to determine the value of everything in the estate, before anything is moved. That sets the foundation for an equitable division of personal property, and ensures the family won t pitch something they mistakenly think is junk.

But often a family s most prized possessions have little dollar value.

Mr. Catanzaro, the Sylvania man from a family of 12 children, says among the things he wanted most from his mother s estate and received were pieces of pink Depression glass.

It wasn t the glass itself that was important: It was a memory, he explains, recalling the day when he and his mother went to a flea market and she admired it. He went back and bought two pieces for her for Christmas.

Sentimental objects have lasting value, he says. As you go through life you re going to look at those things, and it will touch your heart forever. You pick that up and there is a connection immediately.

Still, Mr. Thompson says, It is just stuff. I hope at the end of the day that they do remember it is just stuff.

Contact Ann Weber at: aweber@theblade.comor 419-724-6126.