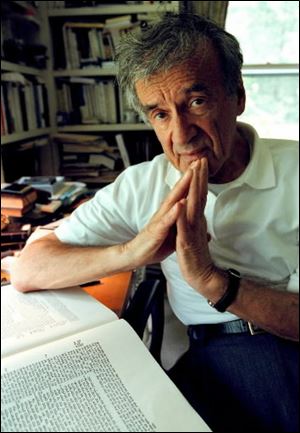

Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel, who will speak at UT, is dedicated to ethical issues

10/18/2008

Elie Wiesel will speak at UT Oct. 30.

Many people use the phrase "Never again!" when discussing the Holocaust.

For Elie Wiesel, it's more than a phrase. It's his life's mission.

The soft-spoken writer and Nobel Peace Prize winner who will give a free public lecture at the University of Toledo Oct. 30 survived the Holocaust and ever since has done everything in his power to prevent more atrocities.

A humanities professor at Boston University and author of more than 50 books, one of the first things Professor Wiesel did after winning the Nobel Prize in 1986 was to establish a foundation to promote peace and human rights worldwide.

The Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity holds forums around the world to discuss urgent ethical issues that confront mankind.

In a recent interview with The Blade, the 80-year-old professor said the foundation had long been a dream, but it wasn't until he won the Nobel Prize that he had the funding and the name recognition to make it a reality.

And once it became a possibility, it became a necessity.

"I simply knew that when they announced the prize that you have to do something," he said. "You cannot just go on writing books and go around giving lectures and so forth. The fact is, if you have a Nobel Prize it opens doors."

The first major project his foundation undertook was assembling 79 Nobel laureates in Paris for a conference in January, 1988, titled "Facing the 21st Century: Threats and Promises."

It was the first time in history that so many Nobel laureates had gathered together, and the conference raised almost impossible expectations.

"There is a little bit of a mistake," Wiesel said. "People think that we have the answers to all the questions. But at least we have the questions. And it's true, people listen to a Nobel laureate better than to other people. That is because they are not politicians, really, and there is no ulterior motive."

At the inaugural conference in Paris, Nobel laureates from all the disciplines and from five continents were joined by French President Francois Mitterand and King Abdullah II of Jordan.

"My appeal to my fellow laureates was and is: 'Look, the world has given us a tremendous amount of good things, and therefore the time has come to give back.' So we use what we are and what we have received in order to help others," Wiesel said.

After the success of the Paris conference, the Wiesel Foundation organized four subsequent gatherings on the same theme, "The Anatomy of Hate," in Boston in 1989; Haifa, Israel, in 1990; Oslo in 1990, and Moscow in 1991, then added "The Anatomy of Hate: Saving our Children," in New York City in 1992.

Other Wiesel Foundation conferences have included "Tomorrow's Leaders," "The Future of Hope," and "Forum 2000."

Wiesel said that in his books, lectures, and conferences the primary goal is to raise awareness of injustice and to inspire people to do something to stop it.

He asserts that the opposite of love is not hatred, but indifference.

"I was fighting indifference. All my work is against indifference," he said. "I believe really it is true that the opposite of love is not hate but indifference. But also the opposite of education is not ignorance but indifference. The opposite of beauty is not ugliness but indifference. The opposite of life is not death but indifference to life and death.

"So the indifference is what permits evil to be strong, what permits injustice to win, what permits catastrophe to go and kill and not stop."

Wiesel was born Sept. 30, 1928, in the small town of Sighet, Transylvania, in present-day Romania on the Ukrainian border. His family spoke Yiddish, and he began religious studies at an early age and was encouraged by his father to study classical and modern Hebrew.

Sighet became part of Hungary during World War II but otherwise escaped the brunt of the conflict until 1944, when the Nazis seized the village and began deporting Jewish residents.

Wiesel, then 15, was crammed into a cattle car along with his parents and three sisters and sent to Auschwitz, the Nazi death camp near Krakow, Poland.

It was a harrowing ordeal, with people packed tightly together and given minimal amounts of food and water. Making it even more terrifying were the repeated screams of Madame Schachter, a middle-aged woman who kept hallucinating that she saw flames outside the window. After nothing else would quiet her, the passengers beat the woman, tied her up, and gagged her.

Upon arriving at Auschwitz, one of the first things the Nazis did was force the Jews to walk past an open pit where they saw the bodies of dead Jews being burned.

Did Madame Schachter's horrific visions foretell the future?

"I don't believe it was a prophecy. A premonition - a premonition is possible," Wiesel said softly. "But that too is a question."

He and his father were separated from his mother and sisters, and young Eliezer did not know the fate of his mother and sisters until he arrived in France after the war. His mother and younger sister had died in the camp, he learned, but two older sisters survived.

Despite his religious training and devout beliefs, the brutality surrounding him forced Wiesel to question and get angry at God.

Even today, he said, he cannot understand how such horrors ever existed.

"The questions remain open. I don't have the answers, and if anyone's trying to give me the answers I say, 'No, I don't accept it.' There should be no answers to such catastrophe. It has metaphysical complications and there should be no answer and if there is, it's the wrong one."

He said, however, that even at the lowest points he never doubted the existence of God.

"Of course I never stopped believing in God. The things I say in [the book] Night, both to God and against God, I stand by every word. But the moment I said that, the next day I went on praying to God."

He said he is "embarrassed" now when he recites prayers he had said in the concentration camp.

"It's cheap flattery when I say to God how good he is, how compassionate he is, how fair, how just. No! But I did say it there."

The Nazis forced Wiesel and his father to march with other prisoners through a blizzard to try to escape the advancing Russian troops. Those who fell behind were shot by the guards.

His father survived the march only to die days later, on Jan. 28, 1945, of exhaustion and dysentery. American soldiers liberated the death camp three months later.

After the war, Wiesel went to France and became a journalist and writer.

But he did not try to write about the Holocaust for 10 years.

"It was a decision I made. It wasn't incapacity," he explained. "I simply I'm a big worrier. I was afraid not to find the proper words, the right words. I come from a very religious background and we have a tremendous respect for words, for language, for what others conceal and reveal in those words. And therefore I said, 'I'll wait 10 years and maybe I'll be ready.' "

He wrote Night, his Holocaust memoir, in his native Yiddish language. Although a slim volume in English, Wiesel said the original book was more than 800 pages thick.

He said he still is dismayed today that world leaders did not intervene to prevent the Holocaust despite news stories detailing the Nazis' persecution and plans to exterminate the Jews.

"It happened in Germany, at that time it was one of the most educated, one of the most cultured nations in Europe," Wiesel said. "How was it possible that it happened in the 20th century, in the heart of Christianity, of Christendom. How was that possible?

"And it happened while the good leaders of the good side knew already and didn't warn us. I think one of the worst indictments in this little book [Night] is when I say that I realized that in 1944, just days before D-Day, we came to a place called Auschwitz and none of us had ever heard that name. Nobody cared enough to tell us, to send messengers to warn us, 'Don't go.' "

Elie Wiesel will speak on "What the Ancient Masters Can Teach Us About Confronting Fanaticism and Building Moral Unity in a Diverse Society," at 7:30 p.m. Oct. 30 in the University of Toledo Student Union Auditorium. The presentation is free and open to the public. No tickets required; doors open at 7 p.m. The lecture is the third in the Edward Shapiro Distinguished Lecture Series.

Contact David Yonke at

dyonke@theblade.com or

419-724-6154.