From microscopic materials, potential industrial revolution

4/17/2005

UT researcher Maria Coleman engineers a polymer soup from which Mr. Azad spins microscopic fibers.

Morrison / The Blade

Buy This Image

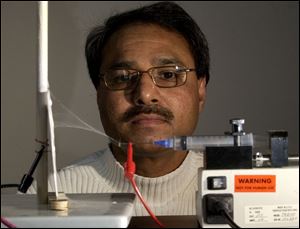

Abdul-Majeed Azad, of UT, checks the progress as a polymer ceramic mixture in a syringe becomes a nanofiber.

Good things, it's said, come in small packages.

Much of University of Toledo researcher Abdul-Majeed Azad's work is so small that it can't be seen without a powerful microscope.

And if his experiments with ceramic nanotechnology progress as he hopes, one day they might provide him with a commercial venture worth millions of dollars.

Nanotechnology involves building specific materials molecule by molecule, enabling a company to remove defects, increase a material's performance nearly tenfold in some cases, and give products properties never before possible.

It offers the prospect not only for better products - enhanced to be lighter, denser, water-resistant, or some other desired quality - but also for vastly improved production.

Nanotechnology doesn't grab as much publicity as manufacturing or the Internet.

But the engineering or manufacturing processes at no larger than a tenth of the width of a strand of hair, visible only by microscope, are big enough that they potentially could revolutionize all industrial sectors.

Some predict that within 15 or 20 years, nanotechnology may rebuild economies or change the way people live. For example, it could lead to cheap manufacturing and easy duplication of designs, allowing poor countries to mass-produce dozens of items, including previously patented ones.

Michigan, fueled by the auto industry, university research, and economic development efforts, is fifth among states in developing nanotechology, according to Small Times, a publication that follows that industry.

Ohio has several industry sectors - autos, electronics, biomedical, aerospace, and building materials - pushing nanotechnology forward, in addition to university research and state government initiatives. It is ranked 10th by Small Times.

The rankings reflect the amount of research and the firms in the field, available venture capital, patents and federal grants awarded, workers' skill level, and overall cost of doing business in the state.

California is far ahead of most states, but Michigan jumped from seventh to fifth and Ohio stayed at 10th (after being 17th two years ago).

Ohio's efforts are mainly around Columbus, Dayton, Cleveland, and Cincinnati.

UT researcher Maria Coleman engineers a polymer soup from which Mr. Azad spins microscopic fibers.

In the last three years, nanotechnology has made inroads in northwest Ohio.

Perhaps 50 to 100 people are involved in academic research locally, forming tiny nanotechnology firms or studying ways to adapt it to existing business processes.

Much of the area's research is at the University of Toledo, but Bowling Green State University is moving into it in biomedicine and photo-chemistry.

"Nanotechnology is a great area for a place like Toledo to invest in because if you talk about automaking, you need millions and millions to get started.

"But you can set up a small company in a garage developing a [biomedical] sensor using nanotechnology and even though you start small, you could end up making millions," said Arunan Nadarajah, interim associate dean for research at UT's College of Engineering.

Nanotechnology can be used in many ways, but the most common is to make cylindrical-shaped carbon nanotubes - strong, flexible carbon tubes about one-50,000th as wide as a human hair and stronger than steel.

Hundreds of thousands of tubes can be grown in orderly formations resembling tightly bundled straw.

The technology also is used to make similar structures called nanofibers - which can be made from carbon, but also from polymers, ceramics, and other materials.

Nanofibers can combine with other types of microscopic fibers to form new materials useful to the aerospace, automotive, and electronics industries.

Nanofibers have been used to make clothing impervious to food stains and to make golf clubs and tennis rackets lighter and stronger.

Fibers can be engineered to hold an electrical charge or resist one, to be magnetic or not, to change color, resist heat, or stop a bullet.

UT has partnered with five other state universities and 65 corporations to try to obtain a $23 million grant from the state to set up a center for researching and making nanotechnology devices.

Toledo's Owens Corning and Dana Corp. are among the 65 companies.

To be called the Center for Multifunctional Polymer Nanomaterials and Devices, the operation wouldn't have a physical location. Funds would be distributed to research sites.

"One of the things we like to talk about is the economic impact that this nanotechnology is going to have on Ohio," said Sharell Mikesell, a former OC researcher who is executive director of Ohio Polymer Strategy Council.

Mr. Mikesell is a co-leader of the statewide effort to get the $23 million center proposal funded. An announcement is expected May 10.

"We're talking about an impact of 20,000 jobs. When you add it all up, we're expecting about 5,000 new jobs and 15,000 upgraded and retained jobs, all by 2010," he said.

Mr. Nadarajah, the UT dean, said job and industry growth efforts tend to focus on more immediate results than nanotechnology can promise.

But some local companies already are heavily involved in the sector.

OC, known for its insulation and shingles, has been involved for years in nanotech research at its Granville, Ohio, technology center, developing nanofibers for use in composite building materials.

Dana has been interested in nanotechnology as it applies to lighter, stronger auto parts, according to UT researchers.

Mr. Azad, the UT researcher, is searching for ways to combine ceramic fibers with substances such as carbon or aluminum to produce stronger, lighter materials, some for armor for the military.

Using a technique that resembles web-spinning, he creates nanofibers from a polymer soup engineered by a colleague, Prof. Maria Coleman.

Nanotechnology, Mr. Azad said, could lead to an economic windfall for the state and northwest Ohio.

"My vision is we'll have another dot-com-like boom, but this will be in nanotechnology," he explained. "There are many small-scale companies popping up right now and they're making good progress. The policy makers are really convinced this is the way to go."

Ohio, through Gov. Bob Taft's Third Frontier technology initiative, plans to spend $20 million to $30 million over the next three years to fund research and projects centered on nanotechnology.

State funds already have gone into research that is delivering products now and that could result in new ones within three years, said Mickey McCabe, director of the University of Dayton Research Institute, which has nearly 370 researchers helping to develop and commercialize technology.

"You've got Wilson [Sporting Goods] incorporating nanofibers in their tennis balls," he said. "The balls are lasting far longer than previously made ones."

In Ohio, Lockheed Martin Corp. is using nanotechnology to develop lighter, strong materials for dirigibles.

John Bedz, director of the state-funded Michigan Small Tech Association, said Michigan is ahead of Ohio now mainly because it has been more proficient in commercializing nanotechnology research.

Much of that, he said, is led by the University of Michigan and Wayne State University.

Michigan set aside $25 million in 2004 to target companies for research grants for nanotechnology and provide 15 percent in funds on top of their federal grants.

Most of the work is being done by universities or private research labs, but large companies, the U.S. military, NASA, and the aerospace industry all are watching, he explained.

"I'd venture to say there isn't a Fortune 500 company that doesn't keep an eye on nano research and looking for ways to use it," he said.

Contact Jon Chavez at: jchavez@theblade.com or 419-724-6128.