SUDDEN DESCENT

Desperate times seize area suburbs

Metro Toledo’s middle class reeling from unemployment, housing crisis

10/31/2011

Kathleen Kress of Perrysburg, jobless since 2008, waits for food at Perrysburg’s Grace United Methodist Church.

The Blade/Dave Zapotosky

Buy This Image

The second in a series

Michael Moore of Perrysburg Township leaves with food from Perrysburg Christians United’s food pantry. The visit to the charity was his first.

A Cadillac pulls into the parking lot of the Perrysburg Christians United food pantry and parks near the back.

A man in his late 50s gets out. His name is Michael Moore. Yes, just like the documentary film maker. No, he’s not related.

But if someone were to make a movie about Toledo, they might cast him as the working-class protagonist: mustache, jeans, tucked-in denim shirt, Tigers ball cap.

He gets in line with 15 to 20 others. There’s Sue Fields, 60, of Rossford, who moved from Florida two years ago to be closer to family but has been unable to find a full-time job. She works 24 hours a week at a Motel 6. There’s Kathleen Kress, 67, of Perrysburg, who lost a job at Dillard’s when the Southwyck Shopping Center closed in 2008. And there are several elderly men and women whose Social Security benefits just aren’t cutting it.

Mr. Moore of Perrysburg Township is typically a talker. He’s a former car salesman, likes sports and politics, is quick with a wisecrack. Today he’s not saying much.

Which is kind of odd. He should be in high spirits. The night before, the Tigers beat the Yankees to earn a spot in the American League Championship Series. The victory, however, was bittersweet; this year, he had to break his annual tradition of taking his teenage son to a game — he couldn’t afford it.

Kathleen Kress of Perrysburg, jobless since 2008, waits for food at Perrysburg’s Grace United Methodist Church.

When he reaches the front of the line, he gives a volunteer his information.

“I’ve never been here before, and I hope I don’t ever have to come back,” he tells her. She assures him there’s nothing shameful about using the pantry, but he doesn’t seem convinced.

Looking for help

A few years ago, during a ribbon-cutting ceremony for upscale shopping center Levis Commons, the then-mayor of Perrysburg told the audience, “No money, no comey.” The statement revealed an often unspoken attitude about the relatively affluent Toledo suburb. Some thought it insensitive. Others took it as a harmless joke. But if suburbs such as Perrysburg have learned anything since then, it’s that the Great Recession has no sense of humor.

The economic crisis has reached deeply into Toledo’s traditionally resilient middle class, wreaking havoc even in the usually recession-proof suburbs.

READ MORE

SUDDEN DESCENT, PART 1: GREAT RECESSION BEGETS A NEW CLASS OF HOMELESS

MAN'S PLIGHT ILLUSTRATES DEPTH OF AREA'S PROBLEMS

Mr. Moore’s situation is a case in point. In the past, he made $70,000 to $80,000 a year, first as a car salesman and then as a driver of a semitractor-trailer rig, hauling plastic pellets to injection molding plants that, in turn, supplied parts to automakers. When the economy crashed in 2008 and the auto industry itself went on the public dole, the trucking company that employed Mr. Moore suffered. He was laid off in May, 2009.

Since then, he’s applied at every car lot and big-box store in town. At one dealership, an interviewer told him the company was looking for someone “who is going to stay with us a long time and extend their career here.”

“I guess that’s a euphemism for saying you’re too damn old,” Mr. Moore said.

Amy Aschemeier gathers food for Sue Fields of Rossford, who works part time but has been unable to find full-time work.

They looked into food stamps or public assistance, but they make just enough money not to qualify — an increasingly common experience for middle-class families whose incomes have been slashed over the past few years.

Desperate for cash, Mr. Moore began buying and selling used cars on his own. For a while, he had a couple of benefactors who would lend him money.

He’d find a good deal, buy the car, clean it up, and try to sell it within a week or two for a profit. It worked a few times and he started doing it with his own money.

In June, he bought the Cadillac — a ‘98 Sedan Deville, the kind of car he and his wife could have bought new back then. The car turned out to be a clunker — the alternator died, then the battery, and now there’s a bulge in one of the tires. “I couldn’t sell it for what I’ve put into it,” he said.

The Moore family’s situation highlights a defining characteristic of this economic crisis — it’s gone suburban.

That bastion of the middle class has weathered recessions of the past, but not this most recent one, in part because this one was fueled by a crash in the housing market, a major source of middle-class wealth.

Here in Toledo, the recession also accelerated the decline of what has traditionally been the bread and butter of the city’s middle class: manufacturing.

A brutal landscape

Some of Toledo’s solid middle-class neighborhoods have been rocked the hardest by the foreclosure crisis. From October, 2007, to September, 2008, the 43612 ZIP code, which includes traditionally middle-class neighborhoods such as Library Village and the Five Points area in West Toledo, experienced more foreclosures than any other part of the county.

Fast-forward to 2010, and the 43612 topped the city’s vacant housing list.

Even before the recession, Toledo’s manufacturing sector was suffering. In 2000, there were more than 60,000 manufacturing jobs in the Toledo area.

After Sept. 11, 2001, that began to decline steadily. When the recession hit in late 2007, those losses accelerated.

By June 2009, there were fewer than 33,000 manufacturing jobs — about half the number 10 years earlier. Although some of those jobs have returned — there were 39,400 in July — economists expect most probably never will.

These factors have produced staggering results. More than one in four people in Toledo live in poverty and the annual median household income has fallen $2,500, from $34,157 in 2008 to $31,708 in 2010.

Lois Ford, on the porch at her home in Sylvania, envisioned retirement as a life of travel and leisure. Instead, she’s had to return to work, as a result of depleting her savings taking care of loved ones.

But what’s so surprising about this most recent recession is its ability to infiltrate suburbia.

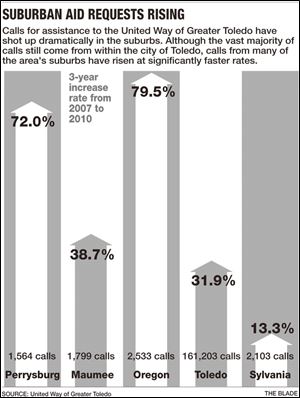

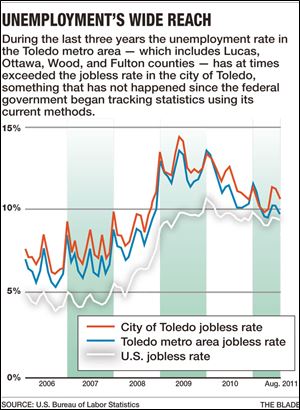

Since the beginning of 2010, the jobless rate in the metro area — which includes Lucas, Ottawa, Wood, and Fulton counties — has at times exceeded the jobless rate in the city of Toledo, something that has not happened since the federal government began tracking statistics using its current methods.

Calls for assistance to United Way of Greater Toledo have shot up dramatically in the suburbs too. While the majority of calls still come from within the city of Toledo, calls from most suburbs have risen at significantly faster rates. From 2007 to 2010, calls from Toledo rose 32 percent, but calls from Maumee, Perrysburg, and Oregon jumped 39 percent, 72 percent, and 80 percent, respectively.

Those trends are in line with what’s happening across the country. Recently released census estimates put the national suburban poverty rate at 11.8 percent in 2010, a 43-year high.

But statistics don’t really tell the story.

Shifting realities

Family House Toledo is the second-largest shelter for homeless families in Ohio. It provides a roof for people from as far away as Tennessee.

But if you want to understand the nature of the economy, you don’t need to knock on the doors of the shelter’s more than 80 rooms. You just need to stop at the office right next to the front door.

Renee Palacios, 36, of West Toledo is the shelter’s executive director. She’s accustomed to helping others. But now, her own family is feeling the desperation she’s spent her life fighting against.

In July, she got a phone call from her husband, a full-time flight controller for BAX Global, an air cargo firm at Toledo Express Airport. She was busy and didn’t take the call. Half an hour later, she got a text from a local media outlet: BAX was shutting down its operations at Toledo Express Airport. All 700 employees would lose their jobs. Almost immediately, friends and family began calling, long before she and her husband had time to think through the ramifications.

“It was probably one of the worst two days of my life,” she said.

Her husband has sent out hundreds of resumes since then. He’s had interviews in Oklahoma and New York, but without luck. Unemployment benefits have cushioned the blow, but only to an extent.

The Palacios have two boys — 3 and 5. The youngest has developmental delays. He’s nonverbal and doesn’t adjust well to new environments. Although it broke their hearts, the Palacios had to cancel his speech therapy. The $20 co-pay for each session was too much. Same with new clothes for their 5-year-old. When school started, Ms. Palacios posted a request on Facebook for clothing.

Like the Moore family, they’ve inquired about help, but with little success. With a master’s and two bachelor degrees between them, a big part of the Palacios’ monthly expenses are their student loan payments. They tried to get a forbearance on those after Mr. Palacios’ layoff, but they still make $3,000 a year too much to qualify. They looked into free and reduced lunches for their son, but again, they didn’t qualify.

Many others are in the same position.

A change in lifestyle

Lois Ford didn’t imagine her retirement this way.

After 30 years with the U.S. Postal Service, she retired in 2003, imagining with it the beginning of a life of travel and leisure.

Instead, Ms. Ford, 63, of Sylvania spent the next six years as a caregiver, first for her father, who died in 2005, then for her husband, who died in 2008, and finally for her mother, who died in 2009. Those efforts drained her savings.

When her mother was sick, she went to the Alzheimer’s Association, but the organization told her it couldn’t help because of budget cuts, she said.

She also tried unsuccessfully for two years to refinance the mortgage on her four-bedroom house to reduce her $1,300-a-month payment, but that didn’t work either.

“I had good credit,” she said. “But I couldn’t get it refinanced because my value decreased.” She finally got it refinanced this year but could have used the relief much sooner.

Finally, she went back to work. Now she spends 30 hours a week chasing around 41 children ages 3 to 5 as a day-care aide at the Sylvania Community Center.

“I really feel like I have fallen out of middle-class status,” she said. “My lifestyle has changed. I feel like I’m going down instead of going up.”

Starting over

Mr. Moore is flipping through the phone book, looking for the number for a collection agency. He had rotator cuff surgery but couldn’t afford to pay the portion of his bill that his wife’s insurance didn’t cover. Apparently, the bill was sent to collections, because now he’s getting phone calls.

As he thumbs through the “C” section, he comes across a listing for a cab company. He used to drive semi trucks, why not a cab? He calls, gets an interview, takes a test, and within a few weeks he’s got his first job in two years and five months.

“I’m going to get a Mohawk hair cut and say, ‘You talkin’ to me? You talkin’ to me?’” he jokes, doing his best Robert DeNiro impression.

“It’s not exactly what I want to do. But what are you going to do?”

The immediate answer for him: settle into the couch to watch a baseball game. Perhaps next year, he and his son will be sitting in the stands.

Contact Tony Cook at: acook@theblade.com or 419-724-6065.