POVERTY & POLITICS

Rural poor face unique challenges

Southern Ohio offers glimpse of a forgotten economic class

5/20/2012

Danny and RaeJean Cantrell fill jugs with water from Buchtel Spring in Buchtel, Ohio. The couple have been using spring water for washing dishes and flushing the toilet since the tap water was turned off at their home.

GLOUSTER, Ohio -- RaeJean and Danny Cantrell moved to southern Ohio, into the hilly swath of the state just inside Appalachia, looking for a place to regroup and restart their lives.

They wanted a fresh start, with cheap rent offered through a friend, because Mr. Cantrell had been hurt years earlier at a job, then spent years out of work. The family eventually lost everything, including a home near Columbus.

Now, after their tap water was shut off, they count themselves lucky that they can get free water for washing dishes and flushing the toilet by driving 10 minutes down a winding road to Buchtel, Ohio, where it flows from three holes in a concrete wall in the side of a hill. Just like the monthly food stamps and welfare cash assistance Ms. Cantrell collects through Athens County Job and Family Services, that natural spring water is not something they enjoy collecting, but it is helping the Cantrells survive.

"Our water has been turned off," Ms. Cantrell said one afternoon while putting in her required 30 hours of weekly work at the Hocking-Athens-Perry Community Action center so she can get her $100 monthly cash assistance check.

Mr. Cantrell interjected: "We were desperate and we needed to get on food stamps. We didn't want to, but we had no choice."

PHOTO GALLERY: Poverty & Politics -- Southern Ohio

Jack Frech, Athens County Job and Family Services director, says poverty is easy to find in Appalachia.

That kind of poverty is not uncommon across Ohio, but it is more likely to be found in the southeastern part than in other regions of the state. Families living in extreme poverty, some without running water or utilities, are easier to find in the rolling, picturesque hills of Ohio's Appalachian countryside than in some areas of Toledo or Cleveland, said Jack Frech, director of Job and Family Services in southeast Ohio's Athens County.

"There was a story in the news recently about some kids living in an old bus, or without running water, and that shocks people. Well, we have that kind of thing all throughout Athens County and other counties in Appalachia. You just have to go back into the hills," Mr. Frech said.

"Poor people in Toledo are no different than poor people in Athens County," he said. "I think there are more services in Toledo, but they have different challenges with safety and security and … a lot of people, especially down here, look at the cities and they say, 'My God, you have buses, you have health clinics all over the place, all that stuff.' And that is all true, but it is also true that you have 10 times more poor people cramming into those buses, cramming into those clinics, waiting to get services at those places."

The swath of America running from Georgia to New York known as Appalachia was, for many generations, known for its extreme poverty. It conjured images of moonshine-swilling locals, barefoot children, and poor dental care. Somewhat isolated, Ohio's portion of Appalachia sits just a few hundred miles from large cities with affluent suburbs where the richest Ohioans live.

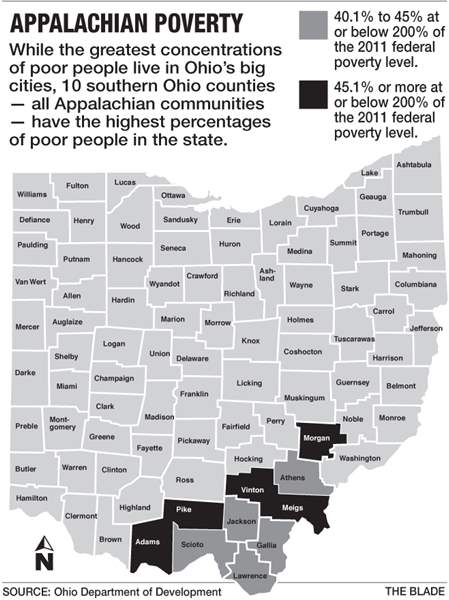

Although the highest concentrations of Ohio's poor are found in major cities, 10 southern Ohio counties near the Ohio River border with Kentucky and West Virginia have the greatest percentages of people at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level, which makes them eligible for certain public programs, according to the Ohio Department of Development.

Forty-five percent of all residents in Adams, Pike, Vinton, Meigs, and Morgan counties fall below that level. Five counties -- Scioto, Lawrence, Jackson, Gallia, and Athens -- are just slightly better, with 40 to 45 percent of the population having that poverty distinction. That compares with 35.1 percent in Lucas County or 30.9 percent in Franklin County, home to the state capital, Columbus.

Enduring despair

A national examination of Appalachian poverty started decades ago. John F. Kennedy visited the region during his 1960 presidential campaign, when the country started taking note of the stark differences in lifestyles between places such as suburban Columbus and Glouster, an Athens County town that fell into despair after the collapse of mining and manufacturing companies.

Now, Glouster owns an unenviable statistic: More than 50 percent of its residents' incomes are below the federal poverty line.

After he was elected, President Kennedy established the Appalachian Regional Commission, its purpose to examine the roots of the region's poverty and recommend solutions. The President's Appalachian Development Act allocated $1 billion to 11 states in the Appalachian region for the development of highways and other projects.

After President Kennedy's death, President Lyndon B. Johnson followed up on his predecessor's efforts and launched the War on Poverty from a porch in Inez, Ky., at the home of a man named Tommy Fletcher, just a 139-mile drive from Athens, Ohio. That was 48 years ago.

The issue of poverty, the fundamental causes of poverty, and how to curtail the number of people on public assistance are political issues for the 2012 election.

After winning the Florida Republican primary, Mitt Romney told CNN that he is "not concerned about the very poor because we have a safety net, and if it needs repair, I'll fix it."

About the same time, President Obama was talking about eliminating tax breaks for the rich.

Former Ohio Gov. Ted Strickland acknowledged that most political contests are dominated by talk about the middle class, deficits, taxes, health care, and, more recently, social issues such as gay marriage. But talk about the poor -- particularly Appalachia -- has chiefly been glossed over.

"Poverty is being ignored and I don't absolve myself of that," the former governor, a Democrat who grew up in Scioto County, told The Blade.

"I talked a lot about the middle class as governor. I didn't talk a lot about poverty, but I tried to protect programs for the poor, but in terms of making it a topic for discussion, I didn't do that very much. The needs of the middle class are so pressing, and if you don't have a middle class, the poor will suffer so much more."

Getting by

RaeJean and Danny Cantrell are using mostly hand tools to demolish a three-story house next to the rundown trailer they rent and live in along with their twin 18-year-old daughters. One of those daughters is heading into the Army, and the other hopes to do the same.

"I am all for her doing that, and I support her 100 percent," Ms. Cantrell said.

She realizes that the military is a successful exit strategy from poverty and Appalachia.

In exchange for the demolition work, the Cantrells' landlord is giving them a discount on rent, but the water is still off. On a break from that work, the couple drive down to collect water from the spring in Buchtel, using plastic jugs.

Steve McGrath, 36, working on an old car to make some cash, barely noticed the couple collecting water, since it's a common practice.

His rugged hands were stained with oil and dirt as he corralled his son and girlfriend's daughter into the back of a pickup truck and pulled it closer to their trailer home.

"I buy and sell cars, do demo work, do what I can. … I'm just a handyman trying to make it," Mr. McGrath said. "I used to party with drugs and beer and pills," he said. "People can go up to Columbus, buy drugs for $9 a bag, and sell it down here for $30 or so."

A 'structural issue'

The reason so many do not prosper in Appalachia is a "structural issue," said Mr. Frech, the director of Job and Family Services for Athens County.

"People all came here because of the extraction industries -- coal, timber, all that sort of stuff -- and when those industries went bust back at the turn of the century or whenever, people were still here," he said. "Essentially, you didn't have the economic development, manufacturing they added in other parts of the state, and it is just not suitable for farming, so that has been the structural problem with poverty down here ever since."

Kathleen Blee, a sociology professor at the University of Pittsburgh and co-author of The Road to Poverty: The Making of Wealth and Hardship in Appalachia, also said the "number one reason for poverty in Appalachia is the lack of good-paying jobs" but added that education has played a role.

"There is an education deficit, but even with education … one of the root causes of Appalachian poverty isn't so much characteristic of the people," Ms. Blee said. "It is more characteristic of the place than the people."

At left, Steve McGrath watches as his daughter, Cheyenne McGrath, 5, and Dallas Snyder, 5, play on a stack of scrap stone that Mr. McGrath plans to sell for extra money. ‘I buy and sell cars, do demo work, do what I can … I’m just a handyman trying to make it,’ he said.

She said many people have left Appalachia for places such as Cincinnati or Chicago. "There has been tremendous out-migration, huge out-migration, so lots of people did move, but there are fewer places to move to and also people are very attached to their homes, and that is not something that is easy to give up," she said.

Bruce Kuhre, a retired sociology professor from Ohio University in Athens and author of Appalachia: Social Context, Past and Present, said coal-industry practices harmed the region more than they helped.

"It goes back to the turn of the [19th] century when the coal interests came into this region and bought up considerable mineral rights … Back in the 1930s, the workers were extremely exploited and the legacy of that coal mining continues to this day in terms of stream pollution and old abandoned strip mines," Mr. Kuhre said.

"Much of the mineral rights were owned by outside interests, so the wealth that was here left and went to the northeast and the workers became victimized."

After World War II, when mines closed down, there was a major out-migration from Appalachia, leaving many of the older residents, he said.

"The main reason for the poverty here is because there has not been creation of jobs. It isn't because the people lack initiative or they are not goal-directed. It is because there are not jobs and if there are, in many cases those jobs do not pay a living wage, so the service sector economy came into play," Mr. Kuhre said.

"I came here in 1965, and I could drive around southeast Ohio and find house after house that was abandoned because there was no work because mines had closed down and people had moved to Detroit because the economy there was up.

"Then we had a recession in 1970s and a lot of people who left and were employed in auto industries came back and lived with aunts and uncles, but the economy never recovered to the level that existed in the 1940s when the coal industry was flourishing."

Terry Rephann, a regional economist at the Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service at the University of Virginia who grew up in the Appalachian territory of western Maryland, said some parts of the area have improved economically, but the majority of it is still disadvantaged.

"There are some areas still dependent on manufacturing in the region and resources like timber and that have been hard hit by the housing downturn and foreign competition," Mr. Rephann said. "So for a region that is still dependent on resources in this globally competitive economy it is going to be disadvantageous for rural areas."

The topography is another reason for the generational poverty, he said.

"Of course, cities tend to be destinations for young people, and Appalachia does not have a lot of large urban areas," Mr. Rephann said. "You can go to any place in the country and if you pulled out the big cities, you would see similar disparities in income and poverty. Basically Appalachia is a very rugged mountainous region, so there are not a lot of places to build big cities."

Confluence of woes

Appalachia, which follows the Appalachian Mountains from southern New York to northern Mississippi, officially encompasses all of West Virginia and parts of 12 other states, including 32 Ohio counties in the southern and eastern parts of the state. Ohio's Appalachian counties are faced with a confluence of problems, according to data collected over years from various state and local agencies.

The Foundation for Appalachian Ohio, a nonprofit group based in Nelsonville in Athens County, said high school graduation rates in that region of the state fall below those in the rest of Ohio, and the rate of adults who have any college or technical school education beyond high school runs generally 20 percent below the state average.

Finding good-quality food shopping, with fresh fruits and vegetables, is a challenge in some Appalachian counties, said Jessica Stroh, a community services division director at the Hocking-Athens-Perry Community Action center in Glouster.

"If you went to the Kroger here, which is the only place people can afford to drive to in [nearby] Trimble, you would be appalled by the lack of variety of food that is available," Ms. Stroh said.

Steve McGrath, 36, leans on one of the trucks that he is fixing while watching his children Cheyenne McGrath, 5, and her half brother Dallas Snyder, 5.

The building is little more than a pole barn, painted a faded blue.

The agency's employment services manager, Kelly Hatas, regularly hears from welfare participants about food choices. "One of our participants was telling me, and she was really upset, that she has to buy all her food at Dollar General cause she doesn't have a car and can't walk all the way down to Trimble from Glouster," she said.

Within all of those 32 Ohio Appalachian counties, 16.7 percent of people live at or below the federal poverty level, compared with 15.1 percent for all of Ohio and 14.3 percent for the United States, according to a report last year from the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services.

In Lucas County, the rate is 18.7 percent, which is 82,619 people.

In 2009, per capita income for the Appalachian counties was $27,979, compared with $35,408 for the rest of Ohio and $39,635 for the United States. Per capita income in Lucas County was $27,851.

Pike County has the state's highest unemployment rate, and the county's Western Local School District was considered the poorest in the state.

Among the state's 88 counties, March unemployment rates ranged from a low of 4.9 percent in Mercer County in western Ohio to a high of 14.7 percent in Pike County. Meigs County's unemployment was 12.7. Vinton and Adams counties were 12 and 12.1 percent, respectively. Lucas County's unemployment rate was 8.6 percent in March.

Looking for work

In the Meigs County town of Racine, Keith Pickens leaned against the side of his pickup truck, parked outside the home he's lived in for seven years, and pointed out over the lush green field nearby.

"It's terrible here," Mr. Pickens said.

Behind him, in the distance and on the other side of the Ohio River in West Virginia, American Electric Power's Philip Sporn plant churns out electricity he can't afford to buy.

"Unless you're born into a family business or marry into it, good luck finding a job," Mr. Pickens said, stroking his long gray beard.

Government jobs or work at any of southern Ohio's coal-fired power plants or someplace like Lakin Correctional Center for women in West Virginia are coveted but scarce, said Rich Wamsley, an employee working with welfare "participants" for Meigs County Jobs and Family Services.

"People really try to get those jobs, but they are fewer and fewer," Mr. Wamsley said.

The 107 people working at the Philip Sporn plant could join the throngs of other unemployed Appalachians when it is decommissioned in 2015.

Phil Moye, a spokesman for Appalachian Power, an operating company for AEP, said some of those workers could be transferred to the adjacent Mountaineer Power Plant, which has 89 employees.

For workers at American Centrifuge Plant, a struggling uranium enrichment plant in the Pike County city of Piketon, fears of more layoffs were allayed in April when the House Appropriations Committee's subcommittee on energy and water agreed to include $100 million for the site in a spending bill.

Supporters say the project will create 4,000 temporary construction jobs and about 400 desperately needed permanent jobs.

Ground down

Back in Meigs County, to the south of Athens County, Mr. Pickens said the prosperity that used to exist in his hometown of Racine was ground down by years of coal mines ceasing operations and factories closing.

"I get food stamps and Supplemental Security Income, so I do OK," Mr. Pickens, 56, said.

About a mile away is Southern High School, a place he attended but quit just shy of graduation.

Mr. Pickens and a longtime friend, who identified himself only as Mr. Hayman, loaded scrap metal into the bed of the beat-up pickup truck and planned to turn it in for cash.

"I live on a whole $50 a week that I get from cleaning a church, and it's 17 miles one way to get there," Mr. Hayman said. "I don't get food stamps or any assistance, except for heat in the winter because I got tired of being cold."

Both men admitted to growing and selling marijuana, well known as a popular side job in Meigs County, years ago.

"This is one of the poorest counties in the state, there are no jobs here, and there's no transportation," Mr. Hayman said. "So a lot of people grow marijuana."

In nearby Pike County, authorities found 22,000 marijuana plants growing on a hillside in 2010.

The Ohio Department of Alcohol and Drug Addiction Services' Ohio Substance Abuse Monitoring Network in March released a report on substance abuse that found crack cocaine, bath salts, heroin, marijuana, prescription opioid, and sedative-hypnotics are "highly available in the Athens region."

"Many types of heroin are currently available in the region," stated the report that covered 16 counties. So-called "Meigs County Gold," a marijuana variety grown there, is "high quality" and so easily available it can be seen growing on front porches, according to the report.

Jennifer Holt, a counselor at Southern High School, said a lack of interest in education is a root cause for the poverty.

"I came from a wealthy [Franklin County] suburban school district, so starting to work at Southern was a very different culture for me," Ms. Holt said. "I feel like, in general, there is almost a lack of appreciation for education, and it's not that the educators are not doing their jobs. It's just that students think education doesn't do a lot for you."

People tend to want to stay in the counties where they grew up, she said.

"There are students who would be very successful in college, but they don't have the support from their families," Ms. Holt said. "As far as our area goes, there are not a lot of jobs, but there are not a lot of people willing to leave."

Contact Ignazio Messina at: imessina@theblade.com or 419-724-6171.