Bank leader vows to save battered euro

Remarks boost expectation of lowered borrowing costs

7/27/2012

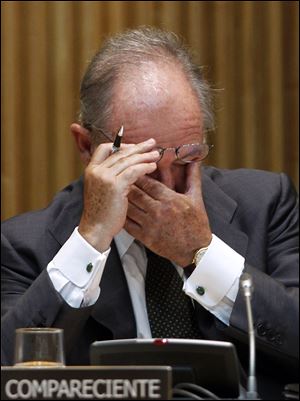

Rodrigo Rato, former chairman of the Spanish bank Bankia and Spain's former deputy prime minister, pauses during a parliamentary hearing in Madrid. High borrowing costs are crippling Spain's economy.

LONDON -- European Central Bank President Mario Draghi promised Thursday to do whatever it takes to save the European single currency and raised expectations that he could step in to lower the high borrowing costs that are crippling countries like Spain and Italy.

Mr. Draghi told business leaders in London that the central bank would "do whatever it takes to preserve the euro" and added, "believe me, it will be enough."

The remarks were made during a question-and-answer session at an international investment conference organized by the U.K. government to mark the start of the London 2012 Olympics.

Although Mr. Draghi was not clear about how or when -- or even if -- he would act, his comments soothed European financial markets.

Analysts said any relief could prove temporary, however, if his words aren't followed up with action.

Fears about the 17 countries that use the euro have intensified over the past few weeks as evidence builds that economies across the region face deepening recessions.

Spain and Italy, in particular, are finding it increasingly expensive to raise money on the debt markets because of spiraling borrowing costs. Investors are losing confidence that the countries will be able to control their debt while they are in recession.

Spain's bond interest rates, or yields, have hit record highs recently as it struggles to prop up its stricken banking sector and meet requests for financial aid from its regional governments. That has raised fears the country may be the next to seek a bailout from the other euro zone countries, following the path of Ireland, Greece, Portugal, and Cyprus.

Spain's economy -- the euro zone's fourth largest -- is much bigger than the other four countries combined and would strain the region's bailout funds.

Mr. Draghi discussed the high borrowing costs being imposed on some countries' bonds.

Using precise, technical terms, he said the bank could react against high bond yields if they interfered with its benchmark interest rate policy, the main tool in steering the euro zone economy and keeping inflation down.

Stocks across Europe rose on Mr. Draghi's comments.

Britain's FTSE traded up 1.4 percent, Germany's DAX index rose 2.75 percent, and France's CAC 40 rose 4 percent.

Spain's main IBEX stock index rose 6 percent and the interest rate on its 10-year bond -- a main indicator of market confidence in a country -- dropped 0.5 point to 6.89 percent. Italy saw a 5.4 percent rise in its stock prices and a 0.3 point fall in its bond rate to 6.07 percent.

On Wall Street Thursday, the reaction was positive.

The Dow Jones industrial average jumped 211.88 points, or 1.7 percent, to 12,887.93. The broader Standard & Poor's 500 index rose for the first time in five days. It was up 22.13 points, or 1.7 percent, to 1,360.02

The gains in the U.S. stock market were broad. All 10 of the industry groups in the S&P 500 index rose, led by telecommunications firms.

In other trading, the Nasdaq composite index rose 39.01 points, or 1.4 percent, to 2,893.25, despite more disappointing news from technology companies including the online game maker Zynga.

"The No. 1 problem in the world now is Europe's finances," said John Fox of Fenimore Asset Management. "When the head of the ECB comes out and says he's willing to do anything, that's code for 'We are going to agree to resolve this issue.' "

Mr. Draghi did not say what the European Central Bank might do to help lower bond rates, but he left markets with the impression that some kind of action was possible. He warned that the bank would stay within the legal restrictions imposed by the European Union treaty that forbid it from directly helping governments.

The central bank has used similar reasoning before to make limited purchases of government bonds to drive down a country's borrowing costs.

Starting in May, 2010, the bank carried out a limited bond-purchase program and accumulated more than $245 billion in bonds. But it had little effect on bond yields, and the program has not been used for several months, despite pleas from Spain for help.

The pressure is on the central bank to act because it is the euro zone's chief crisis-fighter.

The euro zone's current bailout fund, the European Financial Stability Facility, does have about $540 billion in lending power, but most of that is committed to bailouts for Greece, Ireland, and Portugal. A new, permanent fund -- the European Stability Mechanism -- would have nearly $615 billion but has yet to be ratified by euro zone member countries and even then is months from coming on line.