FROZEN OUT

Many struggle with dead-end job hunt

Fruitless searches leave long-term unemployed feeling helpless

1/26/2014

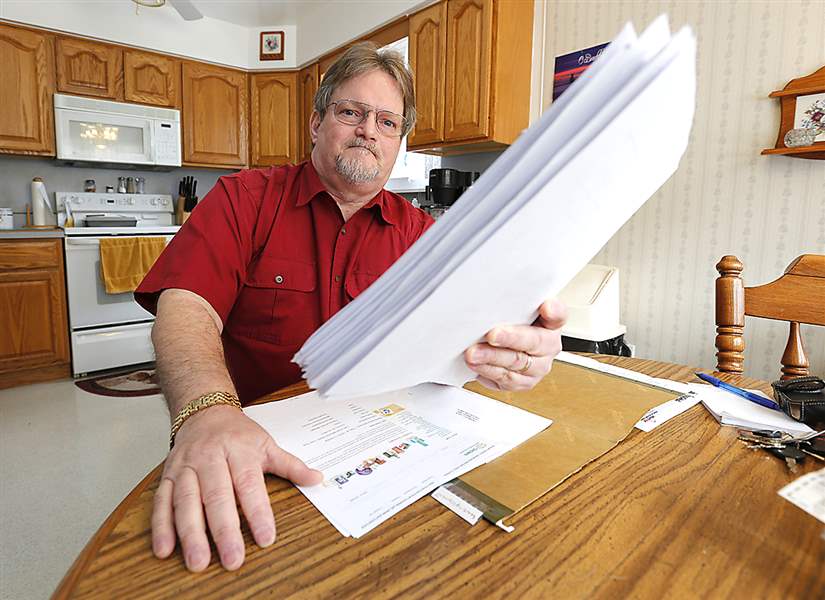

Robert Geis holds a sheaf of job applications in his city home. Mr. Geis, who has been jobless since February, 2013, applies for 15 jobs per week on average.

THE BLADE/JETTA FRASER

Buy This Image

Robert Geis holds a sheaf of job applications in his city home. Mr. Geis, who has been jobless since February, 2013, applies for 15 jobs per week on average.

One in an occasional series

Robert Geis spent 40 years working as a welder, a fabricator, a shop supervisor. He built a solid, middle-class life. Bought a house. Saved for retirement. Avoided debt.

He wasn’t living the high life, but he wasn’t just scraping by. At one time he was salaried, making $65,000 a year as a floor supervisor. Best job he ever had.

But as the economy weakened, his wages fell. In February, he lost an $18-an-hour job where he’d spent the last five years. Eleven months later, he still can’t find work.

Beginning today and continuing over the coming months, The Blade will highlight skilled long-term unemployed individuals who are struggling to find work after being left jobless during the Great Recession.

“I feel helpless,” Mr. Geis, 58, said recently. “I’ve got three different job agencies working for me, plus what I’m signed up for online — Monster, CareerBuilder — and I just can’t get anywhere.”

Millions of Americans are facing the same circumstances.

Even as unemployment rates have decreased, the number of people who have been unemployed for more than six months remains stubbornly high.

According to the most recent data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 3.9 million Americans have been out of work for 27 weeks or longer, the government’s definition of long-term unemployment. What’s more, they make up a historically large portion of the unemployed.

In December, 38 percent of the nation’s unemployed workers had been jobless for 27 weeks or longer. That’s down from a peak of 45 percent, but it remains higher than any other time since record keeping began in 1948. Only once before, after the recession of the early 1980s, did the share even reach 25 percent.

“It is a huge difference from previous recessions in terms of the large number of people who have been unemployed for more than half a year. That is unusual, and it’s lasted a long time,” said Hirschel Kasper, a professor of economics at Oberlin College in northeast Ohio.

Mr. Geis, who lives in Toledo, said he sends out an average of 15 applications a week. Mostly he’s looking in the manufacturing and fabrication industry, though he has widened his search to include more off-the-beaten-path jobs, including a custodial position at the Toledo Zoo.

“I thought that would be a cool job, be outside,” he said. “I got a card in the mail that I was overqualified.”

‘I’m at wit’s end. I don’t know what to do,’ says Robert Geis. Often firms tell him he’s overqualified. ‘Hire me,’ he responds, and ‘you’re getting a new car at half the price.’

Stuck in the middle

In many ways, Mr. Geis feels caught in between.

He can’t find a job here, but he can’t move. He’s stuck in a house for which he owes more than it’s worth. Employers tell him he has too much experience for entry-level jobs, but not enough education for supervisory positions.

“When I go to a job interview for a welding fabricator position, I’m usually told I’m overqualified,” he said. “When I go for a management position, I’m told I need a college degree.”

Why, he asks, wouldn’t an employer hire someone who can do all the job requires and more?

He wonders if “overqualified” means “too old.” Employers can’t legally discriminate based on age, but economists say age discrimination could be an issue for some people.

More commonly, they say firms won’t hire applicants they consider overqualified because they fear those people will continue looking for better-paying jobs and bolt at the first opportunity.

Mr. Geis just wants a job that will allow him to pay his bills.

“As it is right now I have no retirement left, I’ve been divorced twice, I’ve used up all my savings because unemployment don’t pay all the bills,” he said. “I’m down to zilch savings just trying to start over this long.”

Unemployment compensation in Ohio lasts for up to 26 weeks. The benefit amount depends on a person’s previous wages and whether they have dependents, but the maximum someone can receive is $557 a week.

Officials with the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services say the average weekly payment last year was about $317.

Mr. Geis received benefits in the $300 range. He qualified for extended emergency benefits from the federal government, but that program concluded at the end of last year.

When he was receiving unemployment, he and his wife were able to pay their bills. But now they’re struggling to meet their obligations on her meager salary alone.

“I’ve never seen it this bad in my lifetime. In the ’80s, we had a recession and I had a job. I felt the pinch because of the prices going up, but I had a job, I was able to get through it,” he said.

Though he graduated from Springfield High School and attended what is now Penta Career Center to become a certified welder, Mr. Geis never attended college. At the time, he didn’t need to.

“It used to be you could walk out of high school and walk into a plant and land a job making $60,000 to $70,000 a year,” said Mike Veh, work-force development manager at The Source of Northwest Ohio, Lucas County’s one-stop shop for unemployment services.

Those days are gone. A changing job market has placed a higher emphasis on technology, and employers are able to be far more picky in their hiring with such a large pool of job-seekers.

Mr. Geis, again and again rejected for his lack of a college education, looked into getting a degree online.

“I checked it out at ITT [Technical Institute],” he said. “It’s $45,000 for an associate’s degree. If I had $45,000, I’d be able to make my house payment on time.”

Economists say for many people his age, getting a degree doesn’t make a lot of sense financially.

“Clearly the economics are not as solid for somebody in their 50s as it would be for somebody in their 20s. They just don’t have the same number of years to make that return on investment,” said William Even, the Raymond E. Glos professor of economics at Miami University’s Farmer College of Business.

Mismatched skills

That said, there still is a variety of other opportunities for older workers to get new training and certifications.

Many who work with the unemployed say that can be critical, but often the unemployed don’t know what they don’t know.

“One of the things we tend to see is that skills mismatch,” Mr. Veh said. “We hear from companies all the time that they’ve got positions they can’t fill.”

It’s no great insight to say that the U.S. economy is changing. But in many ways, the unique factors of the Great Recession compounded the problems for the unemployed.

“If you hit the sectors of the economy where it’s most difficult for people to transition into other kinds of jobs, you’re going to have more long-term unemployment,” Mr. Even said.

A booming housing industry went bust. And while manufacturing has enjoyed a small renaissance, the number of manufacturing jobs still remains far below peak levels.

According to state data, metro Toledo had about 41,000 manufacturing jobs in 2012. That’s up almost 5,000 from the low point in 2009, but still well below what the area once had. In 2000, for example, metro Toledo had 61,605 manufacturing jobs.

The construction sector tells a similar story. In 2006, before the housing bubble burst, metro Toledo had about 15,000 construction jobs.

In 2012, state data show about 12,000 construction jobs.

“To get people back to full employment, construction workers have to become tech workers,” Mr. Even said. “It’s going to take a long time.”

Still, when you get down to the core question of why so many people have found themselves in a position similar to Mr. Geis’, there’s not a clear, concise answer.

While some have theorized that the extended unemployment benefits may have enticed workers to stay unemployed rather than work, Murat Tasci, a research economist with the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, said data have proven that not to be true.

But he also said recent data has suggested the narrative that long-term unemployment has been fueled by mismatched skills may be overstated.

“This recession was one of the deepest and longest recessions among the postwar recessions. That by itself would produce more unemployed workers,” he said.

“Since the duration is longer and the recovery that followed was quite anemic, I think that can partially be possible for the long-term unemployed.”

Mr. Geis doesn’t know why things have ended up the way they are, and has no great solution, though he doesn’t think ending long-term unemployment benefits was the right move. He’s not ready to give up. Or maybe he is, but what do you do if you give up, he asks. He just wants to catch a break.

“Life is like a big circle. Sometimes you’re on top, sometimes you’re on bottom,” he said.

“Right now I’m on bottom. And I’m having trouble even getting halfway back up.”

Contact Tyrel Linkhorn at tlinkhorn@theblade.com or 419-724-6134.