Among Ohio voters, economy remains most important issue

Is state better off? Depends on how you measure it

3/6/2016

Waitress Terry Muehlfeld, left, throws her arms up in frustration about the economy in Bryan while speaking with Bill Retcher, right, of Bryan, during the lunch hour in Welcome Home Family Dining in Bryan on Febr. 25, 2016.

The Blade/Amy E. Voigt

Buy This Image

Waitress Terry Muehlfeld, left, throws her arms up in frustration about the economy in Bryan while speaking with Bill Retcher, right, of Bryan, during the lunch hour in Welcome Home Family Dining in Bryan on Febr. 25, 2016.

Amid all the bombastic talk about immigration, the fears about ISIS and war in the Middle East, the debate about the future of health care and gun control, and endless punditry about the appeal of Donald Trump, Ohio voters remain zeroed in on the economy.

It doesn’t matter where voters live or how they vote.

More Blade Coverage:

Recovery means little for many across state

Presidential candidates have ideas for Ohio’s concerns

Akron: Ohio economy creates stress across all generations and parties

“The economy is the main thing on their minds,” said Lauren Copeland, the associate director of Baldwin Wallace University’s Community Research Institute.

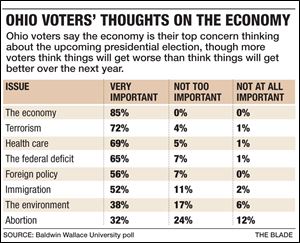

A recent poll from the group found 85 percent of voters say the economy is their top concern as they think about the upcoming presidential election. Baldwin Wallace’s poll was conducted between Feb. 11 and Feb. 20 among 825 likely Ohio voters. The poll’s margin of error is 3.4 percent.

“Immigration and terrorism rank up there, and perhaps those things are a little more salient because of the shooting we had in San Bernardino and the Syrian refugee crisis, but at the end of the day, I think people are concerned about the economy,” Ms. Copeland said.

People have good reason to be concerned.

A study of jobs and median income trends in Ohio conducted by The Blade and other large newspapers in the Ohio Newspaper Organization shows the state has lost more than 250,000 jobs since 2000. Even with the rebound after the Great Recession, the state still has about 80,000 fewer jobs now than it did in 2007.

The goods-producing sector, with its decent-paying blue-collar jobs, has been hit especially hard, falling by nearly a third since 2000. Wages have been mostly stagnant and household incomes have fallen, eroding workers’ purchasing power.

But there’s also another story line, one that’s been a hallmark of Gov. John Kasich’s presidential campaign. In debates, town halls, and campaign stumps across the country, Mr. Kasich has highlighted Ohio’s economic expansion during his governorship.

And it’s true. Ohio’s economy has been growing.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Ohio’s real gross domestic product — the total value of all goods and services produced in Ohio — grew by 2.1 percent in 2014. That was best among Great Lakes states, but slightly below the nation’s 2.2 percent growth that year.

The state also is adding jobs of late. In 2015, the state’s employers added about 73,000 jobs, bringing the total number of jobs added since the depths of the recession to more than 342,000. That’s roughly equivalent to the job losses during the recession.

December was a particularly good month, with private employers adding 15,900 jobs, the fifth biggest gain in the nation. Ohio’s unemployment rate was 4.7 percent in December, lower than the U.S. unemployment rate of 5 percent.

For many Ohioans, the reality lies somewhere between boom and bust. And those realities are likely to play a role in the presidential election.

“I think people are still pretty nervous about the current state of the economy, in Ohio and across the nation,” said Robert Alexander, a professor of political science at Ohio Northern University. “A lot of the numbers look better but a lot of people probably don’t feel that much better and there’s still a lot of anxiety about the economy.”

Political leanings tend to color views on the state’s economy. Presidents have long been linked with the economy, whether or not they had much of anything to do with it. The extension of that has been supporters of President Obama say the economy is strong, while his opponents are far more critical.

“That, I think, is a major filter on how people are seeing the economy,” Mr. Alexander said. “Democrats are seeing one thing and Republicans are seeing something different.”

Baldwin Wallace’s findings support that assessment, with a majority of Democrats saying they believe the economy will improve over the next 12 months. Almost half of Republicans think that the economy will get worse.

Feeling left behind

Other people don’t know what to think, other than a hopeless feeling of having been left behind.

Richard Brandt, 53, of Bryan, is one of them.

Mr. Kasich may talk about an “Ohio miracle,” but Mr. Brandt doesn’t see it. Laid off in 2008 from Alex Products, a Henry County auto parts supplier, Mr. Brandt hasn’t found steady work since.

“It’s got me very frustrated, and nobody is addressing issues I have and [the issues] of the people who are at the bottom because they don’t care,” he said.

Underemployment, he said, plagues older workers who for years had good pay at industrial jobs that are gone. Now on disability, he said his options would be limited to part-time or temporary work if he re-entered the work force.

“Working at some fast food restaurant or gas station does not give you the income level when you were working at an industry that has closed down in the area,” he said.

Economists say Ohio’s shrinking work force over the last 15 years is the result of a number of complex causes. Free trade deals, a more globalized economy, increased automation, and the emergence of China all have cost the state manufacturing jobs. While some of those jobs have returned over the last few years, Ohio and its industrial centers are likely to continue shedding manufacturing jobs.

“It doesn’t mean manufacturing will stop being an important part of the Toledo economy, but just as a share of total employment it’s not likely to go back,” said Mekael Teshome, an economist with PNC Financial Services Group. “This is kind of a long transition. The key is to find new growth drivers.”

That’s not unique to Ohio, it’s just a drawn out process here. Ohio also doesn’t have the demographics benefits of states like North Carolina or Texas that have growing populations.

“Step one in the healing process is job creation, and that’s what we’re doing now,” Mr. Teshome said.

Better-paying jobs — and boosting wages for existing workers — are the next steps. That requires a more skilled, better educated work force, a tighter labor market, and possibly some government intervention by the way of boosting minimum wages, Mr. Teshome said.

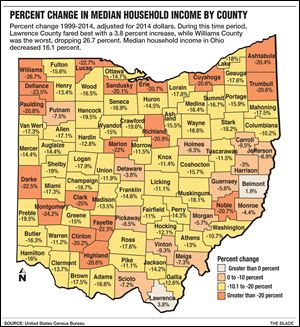

Ohio has fared poorly when it comes to household incomes.

From 1999 to 2014, median household incomes fell in all but two Ohio counties. Three of the five worst performing counties were in northwest Ohio. Median household incomes fell by 27 percent in Williams County, 24 percent in Defiance County, and 23 percent in Lucas County. In inflation-adjusted dollars, that represents a loss of more than $12,200 a year in Lucas County.

Though median household incomes have been dropping across the country, Ohio’s decline is steeper than most. In 2000, Ohio ranked 19th in the nation for median household income. Today Ohio is 35th, the second-biggest drop in the nation.

“What’s clear is that the recovery that we’ve seen in Ohio is leaving far too many working and middle-class families behind,” said Keary McCarthy, head of Innovation Ohio, a liberal think tank in Columbus.

According to a 2014 study from Innovation Ohio, the jobs employers added after the recession have largely been low-paying ones.

Using data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the group found low-wage jobs, defined as those paying between $7 and $13.39 per hour, made up 28 percent of the state’s employment in 2007. By 2013, that share had risen to 36 percent, making low-wage workers the largest category in Ohio’s work force.

More recent analysis wasn’t available, so it’s possible that trend has reversed. Bureau of Labor Statistics data do show that average weekly wages in Ohio increased 4.2 percent from the second quarter of 2013 to the second quarter of 2015.

It’s also important to note that wages and household income are not exactly the same thing. Household income can include Social Security payments, investment income, and other income.

“There hasn’t been incredible growth in that throughout the country and there is a number of explanations for that. The Great Recession obviously hit a lot of households really hard,” said William Even, an economist and researcher at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio.

Mr. Even theorizes one cause of Ohio’s falling median household income could be the retirement of Baby Boomers who are at the peak of their earning power. He also suggested the cost of employment benefits such as health care have been rapidly increasing. That cost doesn’t show up as part of a household income, but it can cut into wage and salary increases.

“Overall the [Ohio] economy seems to be doing fairly well since the Great Recession,” he said. “It could be better but relative to what the rest of the country has done, we’ve done fairly well.”

Ohio’s GDP growth in 2014, for example, ranked 18th in the nation. Ohio has also received accolades from Site Selection magazine for having the second-most major capital investment projects in the nation that year. Site Selection said there were 582 projects in Ohio that included an investment of at least $1 million, created at least 20 jobs, or added at least 20,000 square feet of floor area. Metro Toledo also ranked near the top among cities its size.

Big cities struggle

Still, Ohio metropolitan areas are struggling. The four counties making up metropolitan Toledo — Fulton, Ottawa, Lucas, and Wood — have lost a total of 32,427 jobs since 2000, federal figures show.

Only the Columbus area has done well.

Of the 23 counties that added jobs from 2007 to 2015, five were in metropolitan Columbus. Two key central Ohio counties — Franklin and Delaware — added 45,413 jobs, more than the other 21 counties combined. In total, those 23 counties added 77,048 jobs.

“When you look at the overall state, central Ohio does shine pretty brightly. It even shines brightly from an entire Midwest standpoint,” said Greg Lawson, a policy analyst with the Buckeye Institute for Public Policy Solutions. “Other areas are still struggling.”

Though Mr. Lawson’s group promotes decidedly conservative ideas, such as making Ohio a right-to-work state and cutting taxes, he is hesitant to lay any specific political blame on Ohio’s situation.

“I think what’s hard is if you look at long-term trends and try to parse it by political situations, that is difficult. A lot of this goes back a really long time,” he said.

Though the economy is at the forefront of voters’ concerns, legitimate policy discussions on the topic have been few and far between, particularly on the Republican side.

Mr. Alexander of Ohio Northern said Mr. Trump’s domination of the Republican political discourse is one of the main reasons.

“There has been very little in the way of public policy all together, let alone policy conversation about the economy,” he said. “There really hasn’t been a whole heck of a lot said about what the candidate would actually do.”

That’s frustrating to some voters. Others aren’t surprised.

“I think people want a change but they don’t know what they want,” said Art Goodside, 57, a resident of Montpelier, Ohio. “You’ve got the extremes; on one end you have Bernie [Sanders], almost a socialist, and Trump on the other end.”

Mr. Goodside was laid off from his Fleetwood travel trailer factory job in 2009. He now works at a Walmart, making half what he once did.

His change in economic fortune hasn’t changed the way he votes or the candidates he likes, though he admitted to having a generally unfavorable opinion of most politicians.

“Most of them are looking at the overall, the major metropolitan areas. This area of the country, I think we’re totally overlooked,” he said. “All of them seem to say, ‘This is a rural area, it doesn’t count.’ That’s the legitimate feeling you get.”

Contact Tyrel Linkhorn at tlinkhorn@theblade.com or 419-724-6134 or on Twitter @BladeAutoWriter.