Canine contrast

5/7/2013

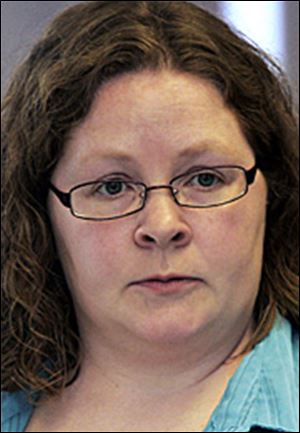

Lyle

Lucas County Dog Warden Julie Lyle continues to show impressive progress at making her agency more humane and responsive, and less reminiscent of the killing ground it was under her predecessor. Sadly, instead of following Ms. Lyle’s useful example, Paulding County is moving in the opposite direction.

Paulding County commissioners said this week that they are removing that county’s dog warden and her assistant. On July 1, the county sheriff’s office will assume the warden’s duties, including operation of the dog pound.

It’s hard to understand the rationale. By all accounts, Warden Georgia Dyson has done a good job of making dogs available for adoption and of seeking options other than killing unclaimed animals. She has routinely made herself available after hours to deal with calls for service.

The shift to the sheriff’s office will cost more, because the deputy who will take over Dog Warden Dyson’s work will be paid a higher salary. The dog warden’s office will be staffed only during the day.

And it’s difficult to imagine, despite county officials’ reassurances, that a police agency will devote as much attention to such matters as placing dogs with rescue groups as Mrs. Dyson has done. Instead, there is likely to be a greater emphasis on executing unlicensed stray dogs, as was the default policy in Lucas County before Ms. Lyle’s arrival.

A report last week by Ms. Lyle to the Lucas County commissioners makes clear the better approach she has taken during her three years on the job. Last year, the dog warden’s office made 711 dogs available for direct adoption — more than three times as many as in 2008.

The office’s rate of “live release” — the percentage of all dogs seized by the warden that are returned to their owners, adopted, or transferred to an agency such as the Toledo Area Humane Society — was 61.3 percent in 2012. That’s a heartening improvement from the 27.6 percent release rate in 2008. So-called pit bulls no longer face virtually automatic death sentences because of their breed, but also are often adopted.

The improvement continues. An event last weekend led to the direct adoption of 45 dogs from the pound — a two-day record for the office, Ms. Lyle said. The warden also makes valuable priorities of recruiting volunteers, providing public outreach and education, sprucing up the appearance of the dog pound, and improving emergency medical care and living conditions for the animals in her charge. All of these practices provide appealing contrasts to the previous insular operation of the department.

Challenges remain. Ms. Lyle must reach an accommodation with Toledo City Council on her office’s response — and its cost in overtime — to animal-control service calls in the city outside standard hours. A proposed measure that would better align the city’s dog law with a new state law that defines vicious dogs could advance the enforcement process.

In the longer term, the county needs to give Ms. Lyle a new, state of the art dog pound with enough space for larger cages. That step, which Cuyahoga County has taken, would ensure further improvement.

Overall, Ms. Lyle is setting a standard for dog wardens that other county governments in Ohio would do well to emulate. She offers a better approach than the discredited model that Paulding County seems determined to follow.