Is experience the best teacher?

10/25/2000

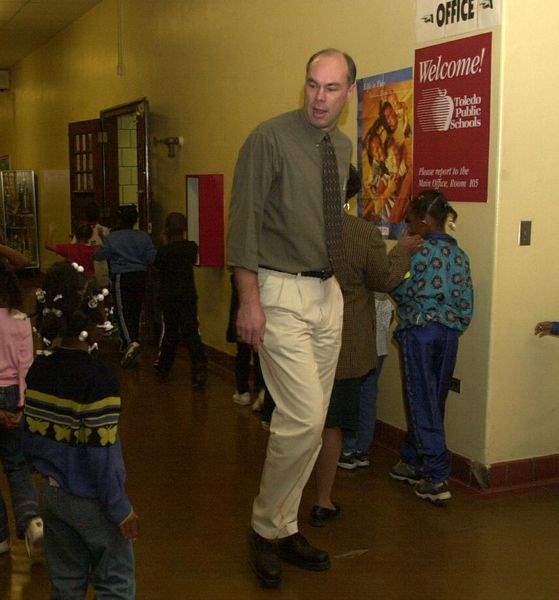

Principal Keith Scott and others were new to Pickett Elementary last year.

When six teaching positions - nearly a third of the staff - opened at Stewart Elementary School in Toledo1s central city this summer, five were filled by teachers with one year or less experience.

Over at Beverly Elementary School, which takes in a more affluent part of town, there were two openings. One went to a new hire to fill a post temporarily vacated by the permanent teacher, the other to a veteran teacher transferring from an East Toledo school.

It is a pattern that is repeated all over the Toledo school district each

year:

The system, similar to the way shifts are assigned in a factory, is the result of the Toledo board of education's hiring practices and its contract with the Toledo Federation of Teachers.

Under the school board's contract with the teachers' union, up for renegotiation on March 30, classroom vacancies are filled automatically by the most-senior, qualified teacher who applies. If no one applies from the seniority transfer list, the central office hires and assigns a new teacher.

Openings that occur in middle-income neighborhood schools such as Beverly, Harvard, and Glendale-Feilbach in South Toledo, and Hawkins and Elmhurst in West Toledo, are usually snapped up by teachers who expect to stay in those schools for the rest of their teaching careers.

The effect was less pronounced this year than in previous years because the school board eliminated 89 teaching jobs because of a threatened budget deficit.

In past years, when hundreds of new teachers were being hired each year, some schools in the poorest parts of the central city would see a 50 per cent change in classroom teachers every year.

Stewart Principal Eloise Carey said the constant turnover is bad for her school and the children. The greatest amount of teacher turnover is in fourth grade, which has had new fourth-grade teaching staffs two years in a row.

"My teachers, being brand new, some of them have never heard of the proficiency tests. Teachers who have taught know the outcomes and know what has to be taught. It's not fair to my children," Mrs. Carey said.

In the latest round of proficiency tests, taken in March, 12 per cent of fourth graders at Stewart passed the math test and 15 per cent passed the reading test.

While teacher transfers fell off this year in Toledo Public Schools, the practice could return to normal levels if a 6.5-mill levy on the Nov. 7 ballot passes. The property tax levy would generate $16 million a year.

Educators are split over the impact teacher transfers have on Toledo's schools.

Those in the teaching ranks say it allows for movement and renewal within the system and gives teachers opportunities that they might not seek if they had to apply and be interviewed.

Others say it results in mere longevity rather than excellence being the basis for teacher appointments.

The Toledo Federation of Teachers, which recently served notice that it intends to hold onto its seniority rights, maintains seniority is at least as good a process as letting "incompetent" principals select teachers. "There is no evidence that total departure from the practice of seniority results in any better placement or mixture of personnel," TFT President Francine Lawrence said. "It would just result in a patronage system for school administrators.

"Teachers in the district don't have confidence in the management to do that right," the union chief said.

She said that the union is cooperating with the administration in trying different ways of selecting teachers. She said she could cite a dozen programs in which teachers were screened for jobs, including the Grove Patterson Academy magnet school in West Toledo.

Teachers conducted the interviews to fill teaching positions at the school at Grove Patterson School in west Toledo.

"The federation supports other means for selecting staff when the instructional programs and practice justify it," Mrs. Lawrence said. The union president estimated as many as 400 teachers were selected jointly by the union and the administration. However, few of those jobs are for classroom teachers.

Many administrators say teacher turnover contributes directly to low proficiency test scores in some inner-city schools.

"It's one of the most incriminating things we do," said Richard Daoust, the former deputy Toledo superintendent, before his departure to a job as superintendent in an Upper Michigan school district.

Keith Scott, the principal at Pickett Elementary in Toledo's central city, said Pickett's performance on proficiency tests over the last several years owes something to the instability in the teaching staff at the school.

At the start of the last school year, 12 or 13 new teachers were on staff, most of them with little or no experience. In addition, Mr. Scott and his assistant principal, Sandra Ellis, were new last year.

This year, there are only four new teachers at Pickett, and there were no changes in school leadership.

The stability of the staff has Mr. Scott enthusiastic about the plans, programs, tutoring grants, and other initiatives that will be launched this year to boost the low proficiency test scores at the school.

"We have a good mix of young staff and old staff, and all of them are enthusiastic and want to be here. I'm confident you'll see a change," Mr.

Scott said.

Either way, Mr. Scott has little control over the policies and personnel in his building.

"They [the central office] basically contact us and tell us who's going to fill a position," Mr. Scott said.

Toledo is not unique in having teaching assignments based strictly on seniority.

Washington Local, right next door, also offers teachers the right to transfer to another school if they have seniority.

In Oregon, a plan negotiated in 1998, allows teachers to transfer within the system based on seniority, unless rejected by majority vote of a committee made up of the building administrator, a teacher in the grade level where the vacancy exists, and the union building representative.

In both districts the transfer must be applied for by mid-May, leaving plenty of time for principals to interview new applicants. In Toledo, the deadline is July 10.

Toledo is also not unique in having its seniority-based system challenged. In the giant Los Angeles school district, Superintendent Roy Romer, a former governor of the state of Colorado, is locked in a dispute with the teachers' union over that very issue.

Mr. Romer now is asking the teachers' union to let principals choose the track and grade-level assignments of their least-experienced teachers. Permanent teachers would retain seniority rights to the remaining spots.

Mr. Romer is advocating, as an alternative to merit pay, which the union adamantly opposes, a voluntary pilot program in which teachers at 55 schools could receive extra cash for improving their students' reading scores.

Other big cities in Ohio, including Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Dayton, require the principal to interview teaching candidates. Many suburban districts around Toledo typically leave the hiring decision mostly to the principal and sometimes the principal and the staff.

Carol Portaro, an elementary school principal in Toledo for six years, moved to Smith Road Elementary in Bedford, Mich., this year.

While complimentary of her last school, Hawkins Elementary in West Toledo as "an excellent school," she said one of the reasons she took an opportunity to leave was the lack of supervisory authority principals have in Toledo.

"If I can't guarantee that I would put my [own] child in every single classroom, then I have a problem with that," Ms. Portaro said. In Bedford, "you're an educational leader. In Toledo, there's a push to just be a manager."

At Smith Road, prospective teachers are interviewed by a committee made up of the school's principal, teachers, and parents. The committee then votes a first and second choice, with the district's superintendent making the final decision.

During her three years at Hawkins and three years at Birmingham Elementary in East Toledo, Ms. Portaro was not asked her opinion on a single teacher who came to work in her schools.

"It gave us absolutely no say," she said. "The principals have responsibility for the success, but yet they have no authority or say over who teaches in the building. Neither do the teachers."

Hawkins -- conveniently close to the suburbs where many teachers choose to live -- is one of those Toledo schools with rare, low, teacher turnover. This year, Hawkins has only one new teacher. The teacher was hired for one year while the permanent teacher is on a one-year out-of-class appointment.

Mrs. Portaro said schools should have the freedom to hire the best teachers and make sure those teachers are willing to share the school's philosophy. "I guess I have a lot of confidence in the teachers and principals in Toledo to make wise decisions for their school," Ms. Portaro said.

At Harvard Elementary School, Mrs. Ulrich does not believe the transfer process makes a big difference.

For one thing, the school often has new teachers in the building holding down jobs on one-year contracts for the permanent teachers who are on special assignment or on leave.

"Of course I would like to, along with a team of staff and parents, choose a team - the Harvard team," Mrs. Ulrich said. But she adds, "I have a great staff."

Richard Lovett, the executive director of teacher personnel, said he tries to send new teachers out for interviews, but that there is not enough time during the intensive hiring period three weeks before the start of school.

"When we have the opportunity we will send a candidate to a school and have them talk to a principal," Mr. Lovett said. "The last two weeks of August are not the time to do that."

Part of the reason most of the hiring is done in August is that the seniority transfer process allows teachers to wait until July 10 to apply for a transfer. That prevents the administration from filling jobs that may be known about as early as May.

Mr. Lovett said many other large districts assign new teachers the way Toledo does, and he said he is not aware of any studies that have said that leaving the hiring decisions up to principals or school teams makes a difference in the quality of teaching.

At Stewart Elementary, seven of the 21 teachers in the school were newly appointed this school year. Of the 18, most have two years or less teaching experience.

And the teaching ranks keep changing. Just last week, a fourth-grade teacher resigned, giving no reason to the principal.

Principal Eloise Carey said she does not blame the seniority system or the teachers. It is just a fact of life tough schools live with.

"Stewart is difficult, according to some people. People are always looking for the quote-unquote easy schools. We're not on that list. I personally love that challenge," Mrs. Carey said.

Beverly has 17 regular K-6 classroom teachers. Only two have less than nine years tenure in Toledo Public Schools.

Some in the black community have complained that elementary schools in mostly white middle-class neighborhoods have more generous budgets than the schools in predominately black and poor neighborhoods.

It is a charge that has some truth, if teacher salaries are any guide. Counting only the regular classroom teachers - who provide the majority of teaching in any school, the average teacher salary in the schools in the Toledo's black neighborhoods is much lower than in the city's white neighborhoods.

The average annual teacher salary at Stewart this year, where the student population is 97 per cent black, is $32,331. The average teacher salary at Beverly Elementary, which is 84 per cent white, is $44,731.

The school district's administration rejects the charge of inequality.

Craig Cotner, an assistant superintendent, said inner-city schools receive services that higher-income schools do not get, mainly the federal Title 1 teachers who help the regular classroom teacher with children who need remedial help, or who pull out children for more focused instruction.

"To say we provide fewer resources to the inner-city is false," Mr. Cotner said.

Indeed, state and federal grants pay for support positions at low-income schools that are not available in higher-income schools.

Warren Elementary, serving a low-income neighborhood near Toledo's downtown, has six staff positions that Beverly, a bigger school, does not have. Those are a counselor, a Direct Instruction facilitator, a pre-first grade teacher, a reading pull-out teacher, and two school-community partners.

While all urban districts struggle with the problem of teachers avoiding or fleeing the difficulties of central-city schools, the practice of having entry-level schools is practically official policy at Toledo Public Schools.

Former Superintendent Merrill Grant attempted to negotiate away the seniority system in the 1997 contract talks with the Toledo Federation of Teachers but backed away at the threat of a teacher strike.

Bruce Douglas, a Toledo businessman who applied for the superintendent position in August, said his first priority if hired would have been to abolish the "governing arrangements" that deny principals and superintendents any say in the selection of teachers who are assigned to their schools.

Mr. Douglas's application was defeated in a 3-2 vote of the school board after the Toledo Federation of Teachers issued a scathing attack on Mr. Douglas's views as counter to the interests of teachers.

"Douglas has made public statements about giving principals the power to hire and fire teachers and strip them of their seniority," Mrs. Lawrence said at the time. "This can only lead to another confrontation in negotiations. Teachers are united in their opposition to both ideas."

The school board hired Dr. Eugene Sanders, a professor and department chairman at Bowling Green State University, as Toledo's new superintendent in August. Dr. Sanders has said repeatedly he will seek to collaborate with the union.

He said experienced professionals seeking more congenial assignments is a national phenomenon.

"What I'd like to use is a model where we use the best resources in the areas that need the most help," Dr. Sanders said.

Dr. Sanders refused to condemn seniority transfers or central-office hiring. He said any system can work if it has the support of the people involved.

"I am interested in improving achievement in this district. I am also interested in doing it in an integrated, collaborative way that empowers people to make decisions at the site where they are most impacted. That

takes a lot of dialogue, a lot of discussion," he said.

David McClellan, the president of the Toledo Association of Administrative Personnel, a union representing principals and other management employees - which also has some seniority privileges - said he hopes the collaboration that Dr. Sanders talks about will result in some give on the part of Mrs. Lawrence.

"If Fran would agree principals ought to play a role in the school - not dictatorial - but with some say over who comes in, who teaches, that's something we would like to see happen in a cooperative fashion," Mr. McClellan said. "I have yet to see a team function well without a coach." Board members Larry Sykes and Terry Glazer were among the most vocal in calling for changes in the teachers' contract in 1997 and 1998.

But Mr. Sykes said he no longer believes in the confrontational approach. He said that taking away teachers' seniority rights would not keep teachers in difficult schools.

"I don't want to force anyone to work where they do not want to work," Mr. Sykes said. "We need to nurture our teachers."

Several years ago he got state Rep. Jack Ford (D., Toledo) to introduce a bill to forgive the school loans of teachers who remain in a central-city assignment at least five years. However, the bill has languished. Board member Glazer believes the seniority transfer policy hurts both affluent and low-income schools.

He said a compromise proposed by the school board in 1998 and rejected by the union would have allowed school staffs to interview the three teachers with the most seniority and make their choice.

"We have to have some kind of system in which we distribute experience more evenly," Mr. Glazer said.

He cited the district's magnet school, Grove Patterson Academy, where teachers were hired based on interviews with the teaching staff. "If we can do it for that school, then why shouldn't we do it for every

school?" he asked.

Grove Patterson, in the Westgate area of West Toledo, was created last year in a partnership between Dr. Grant and Mrs. Lawrence after a bid was submitted by Edison Schools, the national education management organization, to open a charter school in Toledo.

The Edison school never materialized, but Grove Patterson did and is now a pilot for a variety of research-based elementary school practices. Among those are teaming of teachers, foreign languages, and a longer school day. Teachers were interviewed and hired by a committee of teachers appointed by the union, but the school's principal and parents were kept out of the selection process.

Teachers say that high turnover in a school usually occurs because of disenchantment with the leadership in that school.

Others say that teaching in an inner-city school is a demanding job that some teachers view as an obligation to the profession, the way some doctors start their careers in a rural community.

Marcia Rutherford, a teacher at Cherry Elementary School since 1996 who is now on maternity leave, said she loves Cherry school and loves the children. "It takes a special kind of person to stay in the inner city," she said.

"A lot of our kids are so behaviorally involved and have such deficits that it takes a knack. By the time you're there for six years, a change is needed because it is a hard place to work," she said.

"I had half my classroom so behaviorally involved that it was almost impossible to teach. They never learned how to sit in a chair, how to sit quietly and listen. I think that's why our kids are not learning," Mrs.

Rutherford said.

Jane Steger, a teacher who works in the district's school-improvement office, said teachers jump ship for reasons related to support and leadership.

"If you look at the schools with high turnover you will probably find something to do with leadership," she said. "There are many schools, like Lincoln and some of the East Side schools, with high challenging

[conditions] and high poverty, and nobody moves."

One teacher who chose to transfer to an inner-city school even though she had the seniority for a more comfortable assignment is Margaret Greer. Mrs. Greer, who had held out-of-classroom assignments over the past 14 years, opted in 1998 for a teaching position at Warren Elementary School. She described the experience as a jolting one, as she struggled to get -- and keep - control of her classroom.

At home, at night, she practiced raising one eyebrow for the most intimidating effect.

"There are serious behavior problems. This year was better than last year in terms of discipline, and last year was better than the year before," Mrs. Greer said at the end of the last school year.

So far, 2000-2001 "is much better than last year."

TFT President Lawrence denied that the union's contract is in any way to blame for the poor performance of students in Toledo's low-income schools. She said teachers leave schools in which discipline and academic standards are not supported.

The union maintains that principals should be merely administrators, with no oversight of curriculum in a school or of the personnel. The issue is a central philosophical belief of the Toledo Federation of Teachers.

"There's no hope for public education if teachers aren't the instructional leader," Mrs. Lawrence said. "When teachers are the instructional leader, and they act as the instructional leader, they assume responsibility for the practice and the outcome. When we do, we start to see, over time, improvements in student achievement."

Steven Flagg, head of the watchdog group Parents Alliance for Children and Education, claims schools have rejected the help they could get from parents. He contends that schools keep parents at arms' length.

"Regardless of their parenting skills, almost every parent cares and with encouragement and support can succeed," Mr. Flagg claimed. "It is time our board members and school administrators stop pretending they know what is best for parents and ask them."

Toledo's contract issues aside, educational experts say teacher quality and stability in the teaching ranks are crucial for the dramatic increases in learning that society is now demanding.

Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond, director of the National Commission on Teaching and America's Future, said that rapid teacher turnover is harmful to a school.

"Teachers' effectiveness increases sharply over the first three to five years of practice, and then it levels off," Dr. Darling-Hammond said. "If you have a school full of beginning teachers and they're all struggling to put together their curriculum, that can be a concern."

Margaret Greer, the Warren Elementary teacher, can relate.

"The more experience you have, the better you're going to be in any job," said Mrs. Greer, who taught a course in classroom discipline for the University of Toledo this summer. "I had a lot of experience when I went into Warren, but I had not taught first grade ever, and I had not been in a regular classroom for 14 years, and I had an abysmal year. I was awful."