Homework: Too heavy a load?

11/12/2000

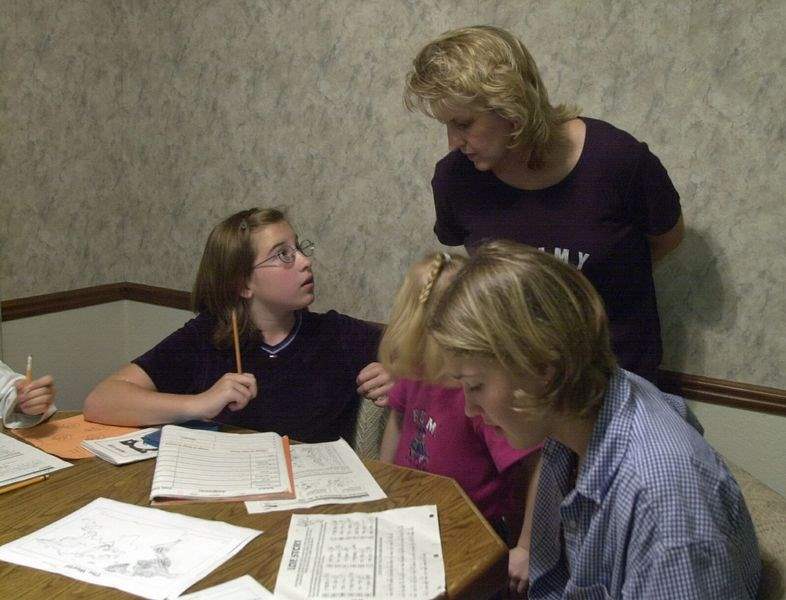

Lynette Westphal, standing, says the amount of homework that daughters Allison Lawrence, 11, left and Amanda Westphal, 16, foreground have disrupts their family life

Gina Thompson, center, sets aside almost an hour every school night to go over homework with Erika, 7, a second grader, and Tyler, 6, a kindergartener, who both attend Grove Patterson Academy. Erika has a 30-minute reading assignment each day.

Some parents rejoice when autumn rolls around and the kids are back in school. Ron and Lynette Westphal dread it.

Back-to-school means this family of six, including two adults working on different schedules, will take a deep breath and jump into the rat race of tightly scheduled nights.

Before the 8:30 p.m. bedtime, there are activities, baths, dinner, clean-up, and lunches to be made. With a preschooler and daughters in fourth, fifth, and tenth grades who like to swim, play soccer, and volleyball, they are busy. Thankfully, they're well organized.

But one school-related task tests their patience, devours enjoyable family time, and sometimes even strains their brains.

Homework.

“We think it's out of control,” said Mr. Westphal, of Sylvania Township. “You work all day and come home and do work for three hours.”

The volume of homework has become a concern in homes across a nation in which time is increasingly precious and academics write about “time poverty.”

A majority of American mothers work outside the home. Children spend more hours in after-school and day-care programs. And academic expectations are higher: More youngsters are expecting to go to college, and school administrators are looking for higher scores on proficiency tests.

Add to the mix the explosion of organized sports for girls and boys beginning at tender ages and continuing nonstop through high school, as well as traditional extra-curricular activities such as music and dance lessons or scouts.

And then, there's HOMEWORK.

Lynette Westphal, standing, says the amount of homework that daughters Allison Lawrence, 11, left and Amanda Westphal, 16, foreground have disrupts their family life

An unmistakable indication of its growth are the bulging 30-pound backpacks which caused the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons to issue special guidelines last year. Jackie Merritt, of Bedford, Mich., weighed the pack her 7th-grade granddaughter brought home on a recent weekend. It was 33.5 pounds.

Teachers refer to parents as their educational partners on the home front. In the last decade, many schools have required students to write each homework assignment in a book that is signed by parents on a weekly or daily basis. Many schools have instituted homework hotlines or Web sites for students and parents who want to check on assignments.

But a new book challenges the ideas that homework is a fact of life, and that more homework is better.

“Belief in the value of homework is so firmly entrenched that most families accept without question this nightly ritual. For many, it becomes a tug of war between tired parents and children. Every parent knows the frustration and anger that often follow: we cajole, yell, negotiate, compromise, and often bribe in order to see to it that homework is done,” write John Buell and Etta Kralovec in The End of Homework: How Homework Disrupts Families, Overburdens Children, and Limits Learning.

“When millions experience difficulties within the privacy of their own homes, perhaps we need to ask why homework too often appears to be a private trouble rather than a public issue,” they write. “Why are we so willing to put up with the imposition on our family lives when we all feel so frustrated about the practice?”

They hadn't planned a book on homework. While examining drop-out prevention programs, they read 40 interviews with high school drop-outs. Every drop-out mentioned an inability to complete homework as part of their reason for leaving school.

The authors question whether education is about producing a skilled workforce in a work-and-spend culture, or about learning democratic citizenship. They say homework favors families who have the most resources, creating an even greater gap between the haves and have nots.

In Piscataway, New Jersey, the school board recently voted to set limits on homework saying it was pressuring students' overscheduled lives, too often dragging parents into it, and becoming a substitute for good teaching.

Piscataway asks teachers to give no more than 30 minutes of homework for grades 1-3, 50 minutes for grades 4-5, 75 minutes for grades 6-8, and 120 minutes for high school. The policy says homework shall not be graded or given as a punishment, and shall be discouraged on weekends. As an incentive, students who complete homework will be given up to an extra 10 per cent on their grade.

“The number and frequency of homework assignments should take into account other school activities that make a claim on the pupil's time,” the policy states.

The Westphals would agree.

The big wooden kitchen table is command central at their Sylvania Township home.

Daughter Allison Lawrence, 11, wants to be a veterinarian or a teacher. She earns top grades, loves to read, and spends 30-90 minutes a night doing school work.

“Some days we could have so much homework that it's like, `Oh, my gosh!'” said Allison, in fifth grade at Stranahan School.

Her parents help her by talking over challenging assignments or typing reports like the one on family genealogy for which Allison interviewed relatives. “We'll type it just to get it done,” said Mrs. Westphal.

Her sister, Amanda Westphal, 16, completes most of her homework in study halls at Southview High School where she's a sophomore. Her dad double-checks her math.

Abby Westphal, 10, is in fourth grade. She'd rather be playing with her Barbies or listening to Britney Spears than chained to the kitchen table, a bunch of erased and re-written work sheets strewn in front of her.

Dr. Sheila Austin, deputy superintendent of Toledo Public Schools

Her dad is trying to teach her how to write 873,622,495 from the words “eight hundred seventy-three million, six hundred twenty-two thousand, four hundred ninety five.” Abby is petite and shy. Gripping a pencil in her left hand, she has written 800 73 600 22 400 95.

Mr. Westphal tries various approaches. “This has got to go in the millions column,” he says. And then: “How would you write eight hundred seventy three?” And, “Try starting at the end and working backwards.”

His dilemma is that of many parents: “Do we let her do it on her own and get it wrong, or help her?”

Abby has a good memory but a tough time grasping concepts. She's in fourth grade and has an educational label of developmental handicapped.

`I feel if they bring something home it should be something they can do,” said Mr. Westphal, who, like his wife, is a mail carrier. Last year when Abby had monthly book reports, he read the books so he could explain them to his little girl.

Educators don't pay much attention to the family life of their students and sometimes view parents as teacher extenders, said William Doherty, author of Take Back Your Kids and professor of Family Social Science at the University of Minnesota.

“Parenting is product development,” he said. “We're beginning to hear from parents about excessive project work that takes the parent's and child's time for long periods.”

Homework should be able to be done by children, he said, and should involve minimal time apart from family activities.

At Maumee Valley Country Day School, the 160 high school students average about three hours of school work a night, said Tom Cambisios. Teachers were asked this year to reflect on why they give homework, he said.

“I think teachers, especially at this school, tend to ask students about the deeper side of things in homework,” he said. “My experience in public schools in New York was too much of it was busy work.”

Of course, homework isn't always blood, sweat, and tears. It seems to be least problematic in households where a parent does not work full time or is well-organized and motivated. It is also successful when a child is not heavily scheduled, and can do assignments competently and compliantly.

But when there's a deviation from that ideal formula, problems can surface. If, for example, the child is unfocused, meticulous, slow, or defiant, homework is likely to mean gnashing of teeth. Same thing if the parent gets home late, is tired, ill, or lacking in motivation or good organizational skills.

When Colleen Meinhold, a Monclova Township nurse, gets home about 5 p.m., her third-grade son has already started his assignments.

“Our entire evening is homework,” she said. It may take longer in her home, she said, because her son is very meticulous and spends a long time ensuring every detail is perfect.

The Meinholds' children are young and their extra-curricular schedule isn't particularly heavy - soccer twice a week in the fall, scouts twice a month, and religious education once month. But the sum total of errands and obligations adds up.

“We're doing something every night. My husband says, `When is there parent time?'” she said. “It would be nice to just sit down and say `how was your day' - have a conversation or read a book. We don't have time to read books at bedtime.”

Two years ago, some members of a parents' club at Meadowvale School in West Toledo sent a letter to teachers asking them to decrease homework. “Please help us to allow our children to have time to enjoy their childhood,” it said. “We would appreciate it if we could come to an understanding concerning a homework policy, expectations per grade level, homework over holidays, on nights when there are school functions, timing and necessity of assigned projects, and other concerns.”

George Offenburg, Meadowvale principal, said the staff discussed the letter and reviewed the Washington Local district's policy on homework but didn't change procedures. “We gave ourselves a reality check,” he said, adding that about 10 minutes per grade-level per night is a good rule of thumb.

Gina Thompson credits her ability to juggle a high-profile job, children, and involvement on many community boards to a strict routine, a helpful husband, Ronald, who works afternoons but is home a few evenings a week, and excellent organization. Moreover, her parents are available to pick up the children from day care, supervise homework, and get them in bed.

Ms. Thompson, mother of children ages 7, 5, and 2, is public affairs representative at Columbia Gas of Ohio. She sometimes puts in evening and weekend hours.

Her older two attend Grove Patterson Academy, a Toledo public school which has an 8 a.m. – 4 p.m. school day and mandatory reading every night.

Arriving home at 6 p.m., the children get a snack while Ms. Thompson rummages through their backpacks. She reads and signs school communications. Then, Erika, 7, begins her 30-minute session of reading aloud to her mother, explaining what she's read, and writing a sentence about it. Meanwhile, Tyler, 5, writes alphabet letters, and Aaron, 2, colors or sometimes watches a movie.

“I try to keep them all in the kitchen,” she said.

They continue their homework as she starts dinner about 7 p.m. That's followed by baths, dinner about 7:45 p.m., and bedtime by 8:45-9 p.m. On nights when there's soccer practice, she'll start homework in the car with Erika reading aloud.

Sandra Hofferth says kids are definitely spending more time on homework.

By analyzing diaries kept by 2,000 households, she determined 6-8-year-olds were diubg almost three times as much homework in 1997 as they did in 1981: 2 hours and 3 minutes a week, compared to 44 minutes a week.

For kids ages 9-11, weekly homework in 1997 averaged 3 hours, 37 minutes, up from 1981's 2 hours, 49 minutes, said Dr. Hofferth, a senior researcher at the University of Michigan's Institute for Social Research. The study does not include teenagers.

In fact, children's total free time has shrunk. They're at home less because of day- and after-school care. And they're doing far fewer household chores and shopping more with their parents, she said.

But homework is an established institution with legions of staunch supporters.

“I'm a big proponent of homework, not a lot but enough to reinforce what they learned and to instill responsibility that they have to do something and take it back to school the next day,” said Robbin Flis, president of the Parent Teacher Organization at St. Joseph's school in Sylvania. “It provides a sense of self discipline.”

Her three sons do soccer, football, basketball, piano lessons, scouts, and Destination Imagination. She works part-time as an accountant and gets home when the children do. Students who don't complete homework at St. Joe's go to a homework room for 45 minutes after school, she said.

Sheila Austin, deputy superintendent of Toledo public schools, says practice makes perfect. “I think it's good preparation for higher education or adult living skills, having to be responsible for something on your own,” said Dr. Austin.

As a parent and English teacher at Central Catholic High School, Charlotte Best says teachers need to be sensitive to family demands. “I realize kids should be active but education must be first,” she said.

Mary O'Brien, mother of five boys ages 6-19, questions whether the increase in homework is linked to proficiency tests. “Why this push to have more homework?” said Ms. O'Brien. “I'm getting calls from parents around the state who are absolutely screaming because their kids are rebelling.”

She is the volunteer Ohio coordinator for Fairtest, a national center for fair and open testing. Her children attend Upper Arlington schools outside of Columbus.

“Just because you shove it down their throat at a younger age doesn't mean they'll be able to do it better when they're older.”

Education and corporations are caught up in “the phenomenon of cramming more and more” into our lives, she said, pointing to the onerous weight of children's backpacks.

“Who is setting this agenda?” she asks. “We're ever increasing our standards, ever increasing our targets which are always moving and always higher. We call it speed up.”

Parents like Mary O'Brien and the Westphals are looking for answers.

“Should the school day be longer? Should vacations be shorter? Less homework?” asks Mr. Westphal. “They need some homework but I don't like it when they bring work home that they don't know.”