More exams slated in Ohio at almost every grade level

1/16/2005

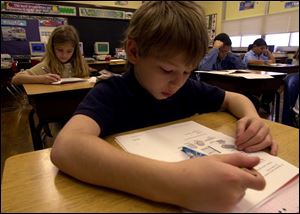

Johnny Przybylski, a fourth grader at Harvard Elementary School, works on a Pre-Ohio Assessment Test to gauge how well he is prepared for the upcoming Ohio Proficiency Tests.

Ali Gross admits she gets a little nervous just before an Ohio proficiency test: sweaty palms and maybe a small knot in her stomach.

But the eighth grader at Timberstone Junior High in Sylvania said she has seen far worse from fellow classmates just before a state proficiency test begins.

"The worst I've seen was in the sixth grade, when someone started crying," said Ali, 13. "You get stressed just before the test, when the teacher tells you how important it is. So if you fail, there are all these consequences."

While the stakes are high for students, who must pass certain tests in order to graduate from high school, they also are high for public school districts nationwide. Poor test scores mean lower state ratings and potential failure to achieve "annual yearly progress" required under the federal No Child Left Behind Act.

Ohio school districts are faced with the challenge of new tests as the state Department of Education replaces its proficiency tests with achievement tests. High school sophomores will take the new, five-subject Ohio Graduation Test in March, which they must pass to graduate.

Over the next three years, the number of exams administered in Ohio will increase at almost every grade level, with new tests from kindergarten to high school. A readiness assessment exam will be introduced for kindergarten next school year.

Toledo Superintendent Eugene Sanders said the new achievement tests will be more difficult and could cause the 34,000-student district to slip back down a notch to "academic watch" - the next-to-bottom category on the state's five-level ranking system. Last year, TPS made it to the "continuous improvement" category.

"We do expect some significant challenges with the new tests," Mr. Sanders said. "But we are planning fairly extensively and that includes our tutoring campaign in February."

The federal No Child Left Behind Act, signed by President Bush in January, 2002, requires that all groups of students be tested and meet the same standards. Schools must raise the achievement rate for students who historically have performed poorly: minorities, special education students, those who live in poverty, and non-English speakers. The law called for school-wide reading and math tests in grades three through eight.

Last week, President Bush turned his attention to high schools when he proposed a $1.5 billion initiative to raise educational standards before students can graduate - a plan that includes annual tests in reading and math.

Area school officials say they understand that there is an increased call for public school accountability and that means more testing. But some wonder if too many exams are administered to Ohio's children.

Many schools in northwest Ohio and southeast Michigan report spending significant time preparing students for state tests, so much so that it permeates nearly every aspect of the educational process. Some teachers, parents, and students call the process "teaching to the test."

Gary Keller, principal of Kenwood Elementary in the Bowling Green Area School District, said the number of exams clearly affects instructional time.

"Last year, our fourth grade took the fall proficiency test and then the five areas of the proficiency test in March. Then they took an additional test which was a pilot test for the state," he said. "That's 17 1/2 hours of testing, which equals three school days. Tell me we didn't lose something in the educational process."

But other educators like Chris Brooks, principal of Bigelow Hill Elementary School in Findlay, view testing differently.

"I'm not anti-test because they can show you strengths and what you need to work on. .●.●. People wanted accountability," Mr. Brooks said. "One of the things people say is that you are 'teaching to the test.' Well, if this was football, you point to the game and teach them the plays they need to win."

The Findlay school designs its regular worksheets to look like the proficiency and achievement tests, which makes the students more comfortable on test day, Mr. Brooks added.

Gary Allen, president of the Ohio Education Association, said the intense push to pass multiple tests each year has taken something away from the educational process at schools.

"What we hear from our members is that, for some of them, the enjoyment has been taken out of teaching because they spend too much time focusing on what's going to be on the test," Mr. Allen said. "At some point, I don't know how you can pile on any more tests."

This school year, Ohio fifth graders are required to take a reading achievement test. By the 2007-2008 school year, there will be achievement tests in reading, writing, math, science, and social studies, plus a writing diagnostics test for that grade.

Seventh graders will take a math achievement test in March. Three years from now, that same class of students will sit down to achievement tests in reading, math, and writing, plus diagnostic tests in science and social studies.

On top of those, districts can opt to administer other standardized exams like the PRO-Ohio Test, which was given to Toledo Public students in grades three through six last week.

Craig Cotner, TPS chief academic officer, said the PRO-Ohio test, which cost the district $203,000 this year, gives teachers an assessment on the children's readiness for the state tests in March.

J.C. Benton, spokesman for the Ohio Department of Education, stressed that the call for testing in grades three through eight is a federal requirement.

"Testing is important because it tells us if our students are learning, and instead of stifling teachers, it can help them use their creativity and best teaching methods to make sure that students learn what they should be learning," Mr. Benton said. "Today, we have academic content standards in the seven core subjects at every grade level from K to 12."

Michigan will not have a third-grade assessment test until next year, as prescribed in the No Child Left Behind law. It does test students in grades, four, five, seven, and eight.

The state has been administering a statewide assessment test since 1971, said Martin Ackley, spokesman for the Michigan Department of Education.

Michigan's standardized test for high school juniors is being replaced with one that will resemble the ACT and an ACT work skills exam.

With the No Child Left Behind Act requiring higher passing rates each year, districts in both states are looking for innovative ways to raise test scores. Along with tutoring, many have started using Internet-based study assistance students can view at home.

Lonny Rivera, principal of Oregon's Coy Elementary, said his school uses a Web site that offers demonstration tests, but he cautioned that it's not a substitute for parental involvement.

"I don't think any administrator would ever tell you they have enough parental involvement," Mr. Rivera said. "A lot of the time, parents may not know what to do to help. Stressing the reading and math at home is important."

Some school districts, including Sylvania, Wauseon, and Anthony Wayne, have hired motivational speakers to talk to parents and students. Thirteen-year-old Ali said she found useful the tips provided by the speaker who visited her Sylvania school on Thursday.

"A big part of it is how to relax during the test," she said.

Contact Ignazio Messina at: imessina@theblade.com or 419-724-6171.