EDUCATION MATTERS

TPS elementary feels pains of adjustment under grant program

With resources come responsibilities

10/9/2011

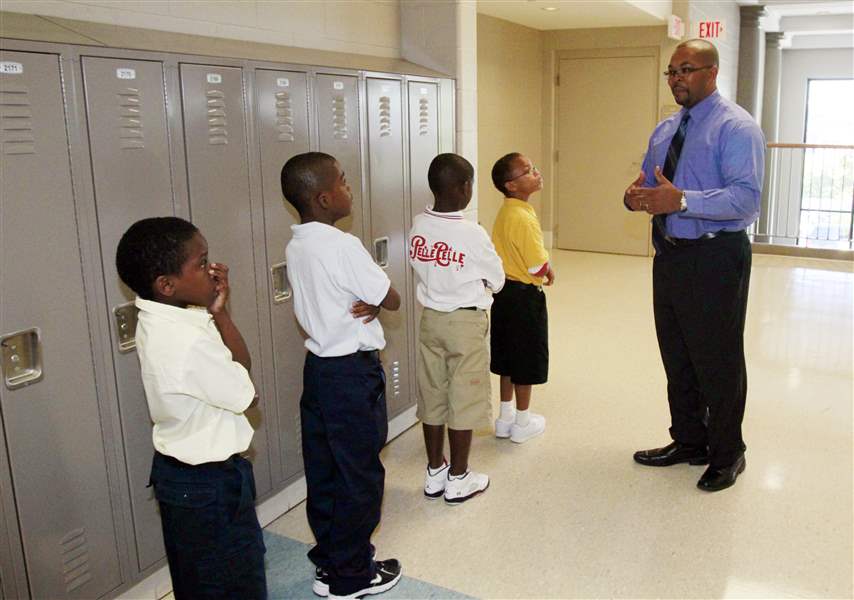

Principal Anthony Bronaugh, right, stops to compliment a group of students who are waiting patiently, quietly and in line for their classmates. Robinson Elementary School, with grades K-8, starts the school year on August 29, 2011. The school is hoping to transform itself with a new principal and with teachers who want to teach there, and who were selected on the basis of their commitment and excellence. The Blade/Jetta Fraser

The Blade/Jetta Fraser

Buy This Image

Principal Anthony Bronaugh, right, stops to compliment a group of students who are waiting patiently, quietly and in line for their classmates. Robinson Elementary School, with grades K-8, starts the school year on August 29, 2011. The school is hoping to transform itself with a new principal and with teachers who want to teach there, and who were selected on the basis of their commitment and excellence. The Blade/Jetta Fraser

Carol Deem weaved through rows of desks, peered over shoulders.

Students, their 14 heads bowed, dug into their work, writing details from a textbook chapter about ancient Egypt, a dual-purpose exercise that teaches history and increases reading comprehension.

The Robinson Elementary room is silent, save for occasional prompts by the teacher as her students write.

"This is your chance to tell a story!" Ms. Deem called out. "Something you liked. Something you felt was important."

Once finished, the seventh graders moved on to math practice sheets. This is not the perceived image of a school system in crisis.

In the perceived image, the stereotype, students should refuse to work and be disruptive or disappear. The teacher should be incompetent, unprepared, unable to connect with a class entirely populated by students of a race different from hers. The technology should be outdated at best and more likely absent.

But the perceived image is not the real image. Not at Robinson. Children learn here. And yet, odds are this year that most of Robinson's seventh graders won't pass state standardized tests.

Will that mean the school failed?

Teachers as students

Their students gone, Natalie Sexton and Sara Barnhill became students.

Most times attentive, sometimes as chatty as their fourth-grade class, the pair joined two other teachers and took notes in the school library about how they'll now approach data. There's constant teacher training at Robinson.

The state last year rated the school in academic emergency, the equivalent of an F. In a bid to turn the school around, district administrators took drastic steps. The school's entire staff was displaced; the principal was removed.

The district was awarded about $6 million in federal funds through School Improvement Grants for Robinson and three other schools. To receive the money, the schools had to make significant reforms. They are eligible for similar grants the next two years if they reach required improvement benchmarks.

One of many new strategies the district is using this year is a team-based approach for teachers to view and use student test data. Teachers hold these discussions informally every day. But this new, formalized program -- the district is calling them Teacher Based Teams -- will be a core component of attempts to boost test scores at schools such as Robinson.

The meetings are highly structured, with designated team leaders, time keepers, and secretaries. The teachers pore over student data, diagnose weak spots and successes, and develop strategies for the coming weeks' lessons. The data for the discussions must be documented. Everything, under the federal School Improvement Grant that Robinson received, must be documented.

District trainers showed Robinson teachers how peers in Lima used the concept and saw dramatic test score increases. The Toledo teachers watched videos on which the Lima teachers discuss how their students did on a recent math test, where they struggled, and how they may teach the subject differently.

Students at Robinson may not start out scoring at the top. But the teachers' job is to at least have their students grow, said Jennifer Lawless, a grant facilitator and one of the trainers. "The goal is just to see some movement," she said.

Courtney Roberts, left, and teacher Carol Deem. Carol Deem teaching seventh grade math and social studies at Robinson Elementary School in Toledo, Ohio on September 29, 2011. Deem is one of about 30 teachers who were specifically chosen to teach at the school where students have historically performed poorly on standardized tests. The Blade/Jetta Fraser

Tough at the top

The tables were turned on Anthony Bronaugh this time.

Flanked by a quartet of district staffers in a meeting room near his principal's office, Mr. Bronaugh was learning just how complicated running a school that received a major federal grant can be. Normally the ultimate voice of authority in the building, this was a moment during which he was the student, and being told no.

The four district employees are Mr. Bronaugh's liaison, and compliance check, for the School Improvement Grant, which provides funding to the school but also comes with numerous strings attached.

The new grant pays for substitutes on Fridays so teachers can meet in their teams. But Mr. Bronaugh also needs his teachers trained in a formative assessment for literacy known by its acronym.

"How can I pay for subs for DIBELS training?" he asked.

The administrators push printouts of spreadsheets in front of him, pointing pens at various columns that represent pools of money. At times, confusion or frustration creeps into Mr. Bronaugh's expressions. This is not a part of being a principal that most people see.

The financial arm of public education is likely its most complicated. The dollars flow from many places into many pots, and what can be used for what and when can be headache inducing.

This year, there's extra money to spend at Robinson, including federal Race to the Top funds and the School Improvement Grant, which led to an overhaul in teachers and a remake of the school's structure.

The funds are both a boon and a burden. With all this extra money and all these extra resources come a bevy of extra requirements and compliance measures. Teachers must train on a specific regimen, sometimes on weekends, sometimes during the school day. Data and plans must be thoroughly documented. And school leaders, particularly Mr. Bronaugh, must shuttle from meeting to meeting, juggle multiple hats, and navigate finance, discipline, and academic hurdles.

The money is there. How and where to spend it is the problem. Mr. Bronaugh wants to find ways to entice parents into the school more often, maybe through holding dinners or offering incentives. But what pot can those funds come out of, he asks.

"Give me something!" he said.

Building something

Robinson is still very much a work in progress.

Walls throughout the school are missing a coat of paint. The sign in the school office still says Robinson Middle School, despite the added grades. And many of the programs that are expected to boost student achievement are still being implemented or even developed.

This year was always going to be about building something.

The school district as a whole, and Robinson in particular, were put in a time crunch this summer. The switch to K-8 schools in just one season meant many schools barely opened prepared. At Robinson, where the entire staff was overhauled, it came down to the wire.

The four Toledo schools that received School Improvement Grants -- Scott High School and K-8 schools Pickett, Glenwood, and Robinson -- weren't approved under the program until mid-July, after repeated delays by the Department of Education. Mr. Bronaugh wasn't selected until Aug. 2, and the teaching staff was picked shortly before school started. That left little time to plan or train.

So programs that would ideally be finished before school even started are still ongoing. Even staffing was unsettled weeks into the year, with more than 100 students enrolling after the first day of school.

Teacher morale is still high. The late enrollment, while an added complication, is a sign that parents are excited about reforms at Robinson.

But the start hasn't been ideal.

"More time definitely would have been helpful," Mr. Bronaugh said.

A new environment

Silence rarely fills the Robinson main office.

The visitor bell constantly rings, pleading entrance for someone outside the locked doors of the school on Horace Street near the intersection of Bancroft and Monroe streets in the central city. Teachers stream in and out to drop off and retrieve mail, meet parents, or make requests with tireless secretary Theresa Lautzenheiser, who is in perpetual motion answering phones, corralling students, apologizing to guests who have waited too long. And always there are the students: Sick, late, in trouble, or lost, they are never far from the office lobby or hallway to the administration's door.

The loudest students are in the room under duress. Teachers send most of them there, after a verbal warning and call to a parent garnered no behavioral change.

Every school office breathes student discontent. Few arrive at the principal's door during class hours for adoration. The changes to Robinson generated new sources of tension but may garner a safer, more disciplined environment.

In past years, students at Toledo's junior highs enjoyed relative freedom compared to elementary schools. But now, with the switch to K-8 schools, older students at Robinson study in a more controlled environment.

They rarely leave their classrooms, and when they do, they are always accompanied by a teacher, except to the restroom. There are no bells. Students meet in a circle as a class before the day starts, a concept called morning meetings that is meant to foster better relationships among students.

At first, students were angry, teachers said. But defiance has lessened. And district leaders say the change has been systemwide. Though there are no solid statistics yet, district administrators say they believe expulsion numbers are down significantly compared to last year.

"I don't think [behavioral problems] will stop," Mr. Bronaugh said, "but I think the atmosphere has changed."

Contact Nolan Rosenkrans at: nrosenkrans@theblade.com or 419-724-6086.