EDUCATION MATTERS

Adversity helped prepare new Robinson principal

His journey lets him relate to students

1/9/2012

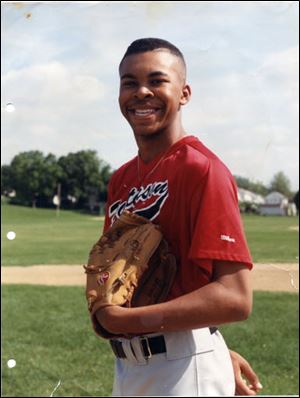

Robinson principal Anthony Bronaugh focuses on the positive. He says an inner drive — and sports — led him to go to college.

THE BLADE/ANDY MORRISON

Buy This Image

Robinson principal Anthony Bronaugh focuses on the positive. He says an inner drive — and sports — led him to go to college.

It's not the sort of thing you should learn from TV.

WHIO-TV anchorman Jim Walbridge read his evening report, telling Dayton residents about a man found shot and killed. Young Anthony Bronaugh watched on a black-and-white TV in his three-bedroom townhouse in Northlake Hills Co-Op, heard how the man's neck was slit, and that he'd been left for dead days earlier.

"And I remember sitting there thinking, 'He's got the same last name as we do,' " he said.

His mother, Yvonne, saw the TV report, the body slumped in a back lot against a fence. But she was tired from work and took no notice. She went to bed and dreamt that dragons and snakes attacked her.

She awoke with Anthony and her sister in bed with her, and a phone call from a sister-in-law. Ms. Bronaugh started crying, and Anthony knew his father was dead.

James. E. Bronaugh was found murdered Aug. 28, 1982, in a back lot off Broadway and Third streets in Dayton. He'd been shot multiple times and stabbed.

Ms. Bronaugh said word on the street was that the elder Bronaugh -- a drug addict who spent plenty of time behind bars -- stole someone's drugs. He was approached at a bus stop, she was told, and shot in retribution.

He fled on foot behind a building, tried to leap over a fence, and fell. Overgrown weeds in the lot where he died hid his body for days. When police found him, he'd already started to decompose.

The case was never solved.

A day with Anthony Bronaugh at Robinson Elementary belies that family past.

READ MORE: Education Matters -- The Transformation of Toledo Public Schools

The principal of the central Toledo school can be found at lunch with his arm around a student, the table of children cracking up at a joke by Mr. Bronaugh. Later in the day, in a suit and tie, he’ll be at a podium in front of parents, talking about math strategies they can bring home.

Mr. Bronaugh doesn’t give speeches to his students about his father’s murder, or the near fatal shooting of his cousin. He doesn’t tell students about being raised in the Northlake Hills low-income housing complex in Dayton. Little of Mr. Bronaugh’s life seems defined by his past or the hurdles he overcame. He barely knew his father.

Instead, Mr. Bronaugh talks about pride in community and self-respect.

And though his focus is on the positive, Mr. Bronaugh’s past helps him understand his students in ways most principals never will.

“When I realized it was my father and that he was dead, I told myself, ‘I don’t want to be that person,’?” he said. “I’m going to be whatever I possibly can to be successful.”

Youth movement

It's not exactly by design, but the Toledo Public Schools district is going through something of a leadership youth movement.

Superintendent Jerome Pecko aside, the district's top administrators are all young for their positions, after much of the superintendent's cabinet left in 2006 when Superintendent Eugene Sanders headed to Cleveland.

The changes have spread to the schools, with numerous new or acting principals, and a fresh crop of new teachers because of an exodus of experienced staff through retirements. Mr. Bronaugh is part of that youth movement.

At age 37, he has been placed in a pivotal role within the district. Robinson Middle School was frequently ranked as one of the worst performing schools in Ohio. It had a reputation as dangerous. The school is set in a neighborhood rife with gangs.

As part of a district-wide transformation, Robinson was completely overhauled this summer. It won a federal grant, but with strings attached that require innovation and marked performance improvements.

And the school is also a possible model for what may work to turn around schools in Toledo. District administrators are paying close attention to the central-city school.

'Engage those parents'

So who was chosen to lead the schools was a major district decision. It was Mr. Bronaugh's work at Sherman Elementary that won him the job.

"We knew in order for Robinson to be successful, we needed someone to engage those parents," TPS chief academic officer Jim Gault said, "... and bring in community support, to help fill the needs that are not academic."

Mr. Bronaugh came to Sherman in 2006, his first principal appointment. The school was in need of help. In that first year, Sherman ranked in academic emergency on its state report card, the equivalent of an F grade.

Mr. Bronaugh mixes a blend of new school and old school approaches to leading a central-city school. He focuses on parent engagement and building partnerships in the community school vein, but he also brings a data-heavy focus.

He fostered a partnership with the Boys and Girls Club, which kept kids in the building after school. He helped implement a concept called social-emotional learning, which focuses on things such as repeated modeling of expected behavior to improve student interaction with peers and staff. He developed a monthly program called "Parent Power Hour," which brings parents into the school and boosts engagement. And he did it with teacher buy-in.

Sports analogies

Anthony Bronaugh enjoyed playing baseball as a youth, left, and cited it as a motivating factor in his life.

An avid sports fan, Mr. Bronaugh constantly uses athletic analogies in school. He told staff that he didn't want his school to be like the Detroit Lions, at that point perennial losers. He wanted to be an up-and-comer, and that started with a new school attitude. The focus was building confidence in the school. He'd ask students, "What's that smell?" and get a response of, "Sherman pride, baby!"

The work brought results. Test scores rose at the school steadily; by 2008-2009, Sherman had moved up a grade, and seemed poised for further improvements.

But then last year was a setback. The school's internal tests projected the school would move up another grade. But as scores came in over the summer, students who left the school during the year but whose scores still counted for Sherman dragged the overall rank down. In the end, Sherman dropped back to academic emergency. Mr. Bronaugh was devastated.

At the Robinson power hour, Mr. Bronaugh told parents he'll sometimes ask boys in the school about how they relate to their fathers.

"Does your father hug you?" he asked.

One response took Mr. Bronaugh aback.

"No, that's some [homosexual] stuff," a boy said.

Many of the boys at Robinson haven't experienced positive affection from a father-figure, he said. Few told Mr. Bronaugh their father says "I love you."

Many, like Mr. Bronaugh, don't know their fathers. Anthony remembers meeting James Bronaugh a handful of times. Once, he refused to answer the door for his father because he didn't recognize him, and had been taught to not let strangers in the house.

His parents were divorced long before the murder. So when Anthony found out his father was dead, it was hard to feel pain.

Tell your boys you love them, Mr. Bronaugh said to the fathers. Give them hugs.

Sports kept Anthony out of trouble.

There weren't gangs in Dayton then, just cliques, he said. Some cliques in his neighborhood sold drugs, some chased girls. His clique played sports.

He taught himself how to play baseball and basketball. He immersed himself in sports, consuming statistics and reciting them at lunch.

'An inner drive'

He watched pro sports and college sports. He knew he needed good grades to stay eligible, and that he needed to graduate high school if he wanted to play college sports. There weren't constant school speeches about the importance of an education. He just knew.

"It was just intrinsic," he said, "an inner drive."

Anthony would organize the pick up games in the neighborhood, and would be the boy in the huddle who drew the next football play in the dirt. Staying on the fields and the courts was better than on the streets.

"He'd say 'We are going to get up at 7:30 in the morning and I'll pitch to you and we'll take batting practice,' " childhood friend Clifton Bullett said.

"I remember saying back then ,'Man, that is so odd.' "

Sports eventually took Anthony to college. He went to a vocational high school and had what he thought was a good job, so he never planned to go to college. On a whim, he went on tours of several universities, largely to try out for their baseball teams, but he ended up staying at the University of Toledo for the classes and groups he joined.

After starting with no plans for college, he ended up with a master's degree. After no plans to leave Dayton, he's in northwest Ohio, with a wife and kids.

In hallways with students and in staff meetings with teachers, Mr. Bronaugh is more likely to crack a joke than a whip.

Sense of excitement

In private, teachers say they're excited to come to the school. Power hour seems popular with staff. There is a sense of shared purpose, and the sense of discontent a splintered building holds is, so far, absent at Robinson. Students seem to connect with their principal.

As one eighth-grade girl put it succinctly, "He cool," rare words of acceptance for an authority figure.

Clifton Bullett grew up in the same low-income housing complex as Mr. Bronaugh, and said his friend was always the leader of their group, and used the same soft touch then, marked with humor and encouragement.

"He was never a person who demanded from you, that you feared," Mr. Bullett said. "You respected him. He had a kind way."

It's hard not to see that Mr. Bronaugh gets his sense of humor from his mother. At times self deprecating, at others sarcastically smug, Yvonne Bronaugh is quick to crack a joke, and has no qualms about laughing at her own.

When asked what was the difference in her son's life that caused him to succeed while others failed, she paused, said, "It was me!" with an unspoken "Of course," then broke down in giggles.

But she speaks the truth. Anthony's father was slain, and some others on his father's side were rough in the 1980s. Yet his mother's side of the family showed the value of hard work.

His grandfather was a successful businessman and an example of success. He also gave Anthony opportunities that his friends never had. While Mr. Bullett's summer vacation might involve a bus trip to downtown Dayton, he said, Anthony might go to Florida.

It was an incentive, Mr. Bronaugh said, to succeed. He let himself follows those incentives, he said.

"I put myself, luckily, in positions that other people were able to help me," he said. "Not monetarily but just in confidence."

Many of the students who go to Robinson don't have that confidence. Many choose to follow the wrong incentives. And so now, Mr. Bronaugh is on to building Robinson pride.

Contact Nolan Rosenkrans at: nrosenkrans@theblade.com or 419-724-6086.