Arizona partnership lets UT study the stars

7/23/2012

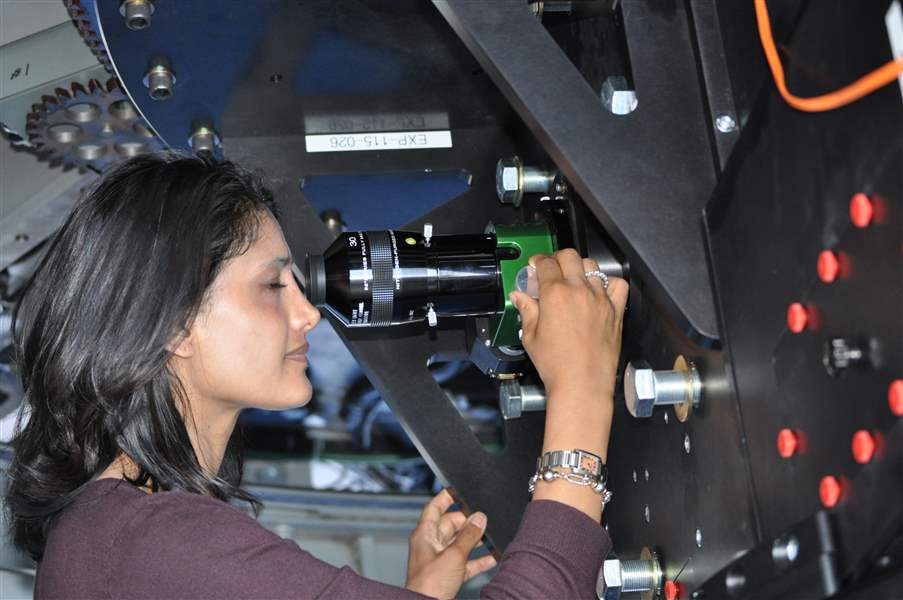

Rupali Chandar, an associate professor of astronomy at the University of Toledo, looks through the Discovery Channel Telescope. Ms. Chandar has previously worked with Hubble Space Telescope images.

UNIVERSITY OF TOLEDO/TOBIN KLINGER

Rupali Chandar, an associate professor of astronomy at the University of Toledo, looks through the Discovery Channel Telescope. Ms. Chandar has previously worked with Hubble Space Telescope images.

HAPPY JACK, ARIZ. — The winding dirt path up to the Discovery Channel Telescope isn't one suited for a rapid ascent. An SUV guided by Lowell Observatory's sole trustee crawled uphill as the 85-foot exterior structure beckoned above.

The trucks that once hauled such massive pieces as the more than 3-ton mirror moved barely inches at a time, thus to avoid a catastrophic slip.

Construction of this new source of discovery was, no doubt, a painstaking process. The University of Toledo's involvement in its impending research is an unlikely match.

Perched at nearly 8,000 feet, atop a cinder cone about 40 miles southeast of Flagstaff, Ariz., the telescope is surrounded by Ponderosa Pine in Coconino National Forest. A scan of the surrounding area reveals little other signs of civilization; its dark skies are perfect for space study.

State of the art

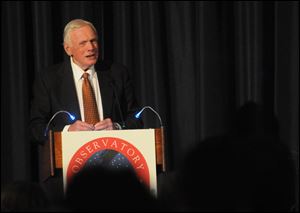

Former astronaut Neil Armstrong speaks at the ceremony commemorating the opening of the Discovery Channel Telescope.

Inside the massive structure, an intricately designed, nearly fully operational 4.3-meter telescope swiveled with grace, the sound of gas brakes interrupting the constant buzz of instruments and excitement. A team of Discovery Communication executives, experienced as few other laymen are with beholding the wonders of science, could hardly contain themselves.

As one executive put it earlier that day, "I feel like I'm walking into a Discovery Channel show."

The fifth-biggest telescope in the continental United States, the DCT, as astronomers call it, is a state of the art telescope. Researchers will use it to make new discoveries involving small galaxies, gamma ray bursts, brown dwarf stars, and more.

This is, in purely scientific terminology, a really big deal.

And the University of Toledo is an integral part of the project. The school's small but spunky astronomy team is one of five partners in the project, joined by the Lowell team, the Discovery Channel, Boston University, and the University of Maryland. The $53 million project took a decade to make.

Researchers, developers, and sponsors affiliated with the project gathered this weekend in Flagstaff to celebrate the telescope's "first light," or the first image taken, a show that the instrument really does work. They keynote speaker was former astronaut Neil Armstrong.

Need for research

While the country scales back, for now, its ambitions in manned space flight and exploration, focusing on endeavors seen as more practical, Lowell has, as they put it, bet the farm on this telescope, risking its very existence on the telescope, a tool of pure research.

In a speech that defended research and space exploration for its own sake, Mr. Armstrong linked centuries old astronomy work to societal advancement, and his own experience in space with the future discoveries that will come from this new telescope.

The future for man, eventually, will be out in space, he said. Research of our universe is imperative.

"The universe around us is both our challenge and our destiny," he said.

He then, nearly 43 years to the date of the historic event, with more than 700 scientists and supporters of the telescope, watched himself land on the Moon, using both archival footage and a re-creation using satellite imagery, narrating until touchdown.

Mankind's understanding of the universe is vastly larger than that day, he said, because of the efforts of researchers such as those involved in the DCT. In 43 years, many will look back and realize how important the telescope's development was, if not from discoveries that jar the public's mind, then from the continual expansion of the public's knowledge.

"Good designs," he said, "withstand the test of time."

Small but talented

Made up of about a half dozen scientists, the University of Toledo's astronomy team doesn't have the world renown of larger, better funded groups.

Referred with a good-natured facetiousness by Lowell's sole trustee William Lowell Putnam III as the "big guns from the University of Toledo," the small team isn't, on its face, the likeliest of partners.

But they're talented, and they're making a name for themselves.

Michael Cushing discovered a new star type, Y dwarf stars, a class of brown dwarfs that are the coldest yet known. J.D. Smith has done work studying the makeup of galaxies and how they die. Rupali Chandar has worked with Hubble Space Telescope images and studied starbursts.

The university's involvement with the telescope is a product of the right connections, the right research, and a willingness to commit to a project that's in many ways unprecedented.

Karen Bjorkman, UT College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics dean, and Lowell director Jeffrey Hall spoke about the project in 2007 while both were on a NASA review panel. The UT dean expressed interest, and Mr. Hall said he might come knocking. In November, the knock came when he emailed with an opportunity to join.

It turns out that the Toledo team's research meshes extremely well with that of Lowell and its other partners.

Star and galaxy life cycles, for instance, are interests shared by other scientists in the collaborative.

The university's board of trustees unanimously approved last month an initial buy-in for $1.4 million, with annual costs of about $125,000.

That buy-in has joined them with some esteemed company.

Lowell astronomers discovered Pluto, proved the universe was expanding, and helped choose the site for Apollo 11's landing on the Moon. Both Boston University and the University of Maryland are significantly larger than UT and have major reputations as research institutions.

But the Toledo scientists are used to outperforming their size.

"They've got a great reputation," Mr. Hall said. "The people they've got are extremely high quality."

That quality should only grow with this new project. Though team members have for years done important research using space based telescopes such as Hubble and one recently launched by the European Space Agency, the school's lack of a dedicated, high quality ground based telescope in many ways limited its competitive draw. The team tried for decades to gain dedicated access to a telescope without success.

"It was one of the things that was lacking in our program," Ms. Bjorkman said.

Dedicated research time

The DCT will allow UT researchers extended, dedicated time for their projects, something that's nearly impossible to get without an investment such as the one the university made in this telescope. How time will be divvied up isn't yet finalized; Mr. Lowell Putnam said the telescope will have at least 300 days of observation, and likely much more.

The telescope will primarily be used by Lowell astronomers, with about 40 percent of research time dedicated to its three university partners. Toledo researchers will probably get at least 20 dedicated days a year at the Arizona facility.

"This is going to take astronomy at the University of Toledo to the next level," Ms. Chandar said.

Since Lowell had never undertaken such an ambitious project, interest to join in the collaboration was tepid during development. That helped create the opening for UT.

There's several features of the Discovery Channel Telescope beyond its upfront specs that will make it a workhorse for research. It's incredibly versatile, as the partners can use nearly any astronomy tool they'd need on the DCT. The telescope is made to support research of numerous natures.

That means that new technology won't pass the telescope by; scientists can add on the latest gadgets as they develop.

"It's almost somewhat of a blank slate," Mr. Smith said.

The telescope can also swiftly shift where it's pointed, allowing rapid responses to events. That will garner valuable research in gamma ray bursts, for instance, which are short-lived.

And its possible that research by UT astronomers could appear in future Discovery Channel shows.

Now that the telescope is proven to work, and researchers ramp up its capability, more teams will probably want access and wish they'd gotten in on the ground floor.

"I think in a year, people will be clamoring to get in, and the door will be closed," Ms. Bjorkman said.

Contact Nolan Rosenkrans at: nrosenkrans@theblade.com, or 419-724-6086