TPS struggles with issue of truant students

Absences at core of controversy about state report card scores.

8/12/2012

Hundreds of Toledo Public Schools students go missing from their schools for days, sometimes weeks, at a time each year.

Nobody staples photos of the children to telephone polls. Police don't issue Amber Alerts. The children aren't really gone, but truant. When school bells ring across the city, too many students just don't show up. Some are teenagers who eventually will drop out. Others are young students living with adults in crisis. Still others live with parents who just don't care.

It has been these truant students at the core of the data manipulations swirling around Toledo Public Schools and other Ohio districts.

Most disputes of school test integrity involve outright cheating: teachers or principals changing students' answers or providing help during tests. But the manipulations — at least in Toledo — look like an urban district struggling to account for students who don't show up, in a vacuum of guidance from state authorities. How should schools account for students they never really taught, since they didn't show up?

"It really is convoluted," TPS Superintendent Jerome Pecko said of state rules. "It begs for clarification."

Not as convoluted are the numbers.

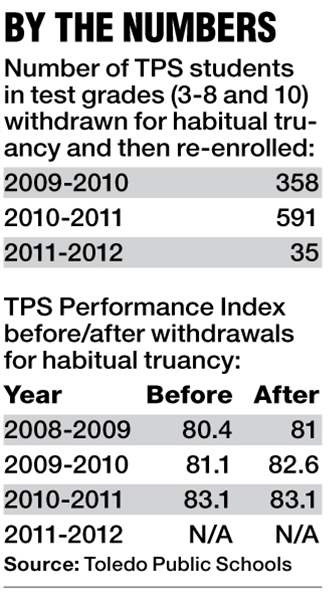

The state test scores for about 5 percent of TPS students did not count toward the district's report card in the 2010-2011 school year. Scores of nearly 600 students who took the state tests were effectively erased that year by district administrators.

Principals, under the direction of top TPS administrators, withdrew students who missed five days in a row and 20 total days in a year, then re-enrolled them. Because state rules count only students continuously enrolled at a school throughout the year, the withdrawals washed the students' scores off TPS report cards.

Mr. Pecko acknowledged the withdrawal policy, a manipulation technique carried over from prior administrations, last month. The practice — which was not unique to Toledo — now faces intense scrutiny at the state level, with investigations by both the Ohio Department of Education and the state auditor.

It's easy to look at the manipulations on their face and see another dastardly cheating attempt, and they may have started as such.

But consider this: Despite the hundreds of students removed from the rolls that year, the practice provided absolutely no help to Toledo Public Schools' school-year report card.

A preliminary report from June, 2011, provided by TPS to The Blade, showed the district would have received a Performance Index score — a weighted average of all students' scores — of 83.1 last year. That report would have been before most of the withdrawals were entered into computer systems.

The official score for TPS, released two months later, was exactly the same, even though hundreds fewer scores were counted.

Data reporting

The practice wasn't always so innocuous. The year before, TPS gained 1.5 points through the practice. The gain is small in the long run, but is also similar in scale to what the district has gained in recent years, meaning the practice added about a year's worth of growth to TPS' 2009-2010 test scores.

Although test scores — along with attendance rates — are affected by the TPS practice, no district officials ever alter the state test scores, Julie Noone, TPS director of accountability, assessment, and research, explained.

Data reporting for schools is a complicated process. In a general sense, it works like this:

After students take state tests in the spring, the test packets are sent to a vendor that scores the results. After the vendors score the tests, they send the results back to districts in a computer file. Districts then correct those files for irregularities, such as students listed for one school when they attended another.

The corrected computer files are then sent to the education department. All that is done before TPS withdraws students.

No current TPS officials interviewed for this story could say for sure when the withdrawal policy started, but most say they believe it dates to the Eugene Sanders administration. Back then, the figures were altered at the district level. Now, principals do the manipulation.

Assistant superintendents Brian Murphy and Romules Durant, under supervision of chief academic officer Jim Gault, annually hold meetings with all building principals to review data report procedures on such reports as "Where Kids Count," which tells principals which students' scores will count for which school, based on enrollment data.

Code ‘71'

Different codes are taught to staff to use for different withdrawal reasons, such as for students who graduated, who died, or were permanently expelled.

One of the codes, 71, is for "Withdrew Due to Truancy/Nonattendance." TPS trained principals — actually, in many cases secretaries did the paper work — to code students who missed five consecutive days and 20 days total with unexcused absences as "71," and then re-enroll them.

In an ironic twist, automated computer systems at the education department, using linked student ID numbers, actually removed the test scores from Toledo's report card. Although the action was initiated by TPS, the state did the actual scrubbing.

"I don't think they would have even known," Ms. Noone said, because it's doubtful humans ever even watched the process happen.

The district didn't just remove students who were taking tests. Even those in non-testing grades, such as kindergarten, that met the policy were coded as withdrawn, then re-enrolled, on the "Where Kids Count" report. In total, 1,100 students were "71" withdrawn during the 2010-11 school year, nearly half in non-testing grades, and then re-enrolled. The impact to attendance rates were minimal, at probably less than a percent.

The bigger impact

While test scores stayed the same last year, despite the practice, the bigger impact could be at the building level.

Just a handful of students' scores could trigger a change in building designation. A low enough building designation could make students in the school's attendance boundaries eligible for private school vouchers. More schools eligible means more vouchers and more students possibly leaving the district, which results in more state funding directed away from TPS.

It's hard to tell how much impact past instances of student withdrawals had on TPS schools. But internal district emails reviewed last month by The Blade showed principals discussing potential swings of more than five index points, depending on the number of students excluded on this year's report card.

"Well I sure hope we will be able to do some attendance exclusions," Teri Sherwood, principal of Walbridge Elementary, wrote to Mr. Durant on June 20. "My unofficial calculated [Performance Index] ranges from a high of 87.05 to a low of 81.45 depending on what I may be able to exclude. Those darn special education scores can kill your PI, especially with the swing getting away from Alternate Assessments again … keeping my fingers crossed."

The Alternate Assessments referred to by Ms. Sherwood are the tests many special education students take instead of the typical Ohio Achievement Assessments; most of those test scores are given a "basic" score — the second lowest possible — regardless of student performance. A high number of Alternate Assessments means a lot of "basic" scores, a drag on the overall Performance Index. Urban districts tend to have large numbers of students with disabilities — last year, nearly 16 percent of TPS students were disabled, according to state report cards.

If those students were withdrawn, their scores wouldn't count.

Although the students' scores were removed, it's not that Toledo Public Schools ignores truant students until the end of the year. The annual exodus is just too large for current efforts to make much of a difference.

"We get in trouble when we do something," one administrator said, referring to parent and political pushback over truancy enforcement.

Last year, the district held 700 attendance hearings for students with excessive absences. About 300 cases were referred to a court mediation program that tries to keep parents and students out of the criminal justice system. Not all of those interventions worked. The district referred more than 500 cases to the Lucas County Juvenile Court because of truancy.

Practice not hidden

What puzzles TPS officials the most is how forcefully state officials have denounced in recent weeks a practice that wasn't exactly hidden.

The withdrawal policy was openly discussed between district and building administrators for years, as TPS officials admit and emails show. The "71" withdrawals were sent directly to the education department; any close scrutiny of the data over the past eight years would have brought logical questions about TPS practices.

A 2008 story in the (Cleveland) Plain Dealer detailed extensive test scrubbing — the exclusion of test scores — in the Cleveland district under Mr. Sanders, who left TPS for the larger district. There are legitimate reasons to scrub many scores, but the practice is similar in many ways to what TPS now admits to doing. And yet, despite the publicity, school districts say the education department sent no emails, no memos, no directives about the practice in the months that followed.

"Why nothing came out with clear and precise directions from ODE is puzzling to me," Mr. Pecko said.

A change this year

This year, the "71 withdrawals" are nearly nonexistent in TPS because Mr. Pecko stopped the practice before the annual summer purge. But that doesn't mean there were no withdrawals in the district.

Student withdrawals are an alarmingly frequent feature of urban, high-poverty districts such as Toledo Public Schools. In the 2010-2011 school year, there were nearly 6,000 withdrawals — not including dropouts — in the district; if those students actually left the district, they'd constitute about a quarter of TPS' enrollment that year.

Many of those students, TPS officials said, don't leave the district, and many others who do leave eventually return. The withdrawals are a result of the extreme mobility of poor students. During the 2010-2011 year, nearly 40 percent of students at TPS schools in academic emergency changed schools at some point. Some leave for myriad charter schools that dot the city. Many others transfer between TPS schools, sometimes multiple times a year.

Each of those departures counts as a withdrawal, because the student officially left one building and enrolled at another. State rules ensure that the student's test scores don't count against the school he left, because another school is now responsible for his education. Those withdrawals are legitimate.

The habitually truant withdrawals are different. They often come from the same general pool of students: those from unstable homes, with parents who are either unwilling or unable to make sure their children get to school every day. The students disappear, sometimes for weeks at a time. Many urban educators have long lamented that it's unfair for schools to be judged on students whom they don't even have the opportunity to teach.

But these students didn't withdraw to attend another school. They just stopped coming. They could come back. These are the students who most need interventions. Fair or not, they are still their original schools' charges. Withdrawing those students and removing them from the test results doesn't just say their scores don't count, but essentially that the students didn't exist.

Just removing the students from the rolls doesn't seem a solution. Counting them the same as other students may not, either.

"Maybe there ought to be two report cards," Mr. Pecko said.

Or maybe schools can find better ways to get kids to show up.

Contact Nolan Rosenkrans at: nrosenkrans@theblade.com or 419-724-6086.