UT astronomers doing their part to unravel mysteries of the universe

10/1/2012

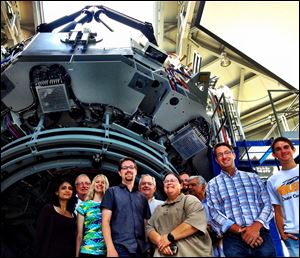

Representatives of UT's astronomy team at Lowell Observatory outside of Flagstaff, Arizona. From left to right, Dr. Rupali Chandar, associate professor of astronomy, Dr. William McMillen, provost and executive vice president for academic affairs, Lesley Simanton, 4rd year graduate student in physics and astronomy, Dr. Michael Cushing, assistant professor of astronomy and director of the Ritter Planetarium, Joe Zerbey, UT Trustee, Dr. Karen Bjorkman, dean of the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, distinguished university professor of astronomy, Carl Starkey, 5th year graduate student in physics and astronomy, Dr. S. Amjad Hussain, UT Trustee, Dr. J.D. Smith, assistant professor of astronomy, Adam Smercina, sophomore undergraduate student in physics and astronomy. All the doctors are PhDs, except for Dr. Hussain, who is an MD.

University of Toledo/Tobin Klinger

Representatives of UT's astronomy team at Lowell Observatory outside of Flagstaff, Arizona. From left to right, Dr. Rupali Chandar, associate professor of astronomy, Dr. William McMillen, provost and executive vice president for academic affairs, Lesley Simanton, 4rd year graduate student in physics and astronomy, Dr. Michael Cushing, assistant professor of astronomy and director of the Ritter Planetarium, Joe Zerbey, UT Trustee, Dr. Karen Bjorkman, dean of the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, distinguished university professor of astronomy, Carl Starkey, 5th year graduate student in physics and astronomy, Dr. S. Amjad Hussain, UT Trustee, Dr. J.D. Smith, assistant professor of astronomy, Adam Smercina, sophomore undergraduate student in physics and astronomy. All the doctors are PhDs, except for Dr. Hussain, who is an MD.

The heavens and heavenly bodies have always fascinated man. Th e sun, the moon, and the stars have been the source of wonder, myth, and at times fear. Ancient mariners learned to use stars as their navigation tools and mapped sea routes.

Astronomers are still gazing at the heavens but unlike their predecessors who used heavenly bodies as milestones and torches on their perilous journeys, they are exploring the heavens and are unraveling the mysteries of the universe. They do it while keeping their feet firmly planted on earth and peering into the heavens with powerful telescopes to find tell-tale clues to the nature of universe.

University of Toledo scientists, along with their peers at other institutions, are making breathtaking discoveries.

The latest addition in their armamentarium is the new Discovery Channel Telescope that was recently commissioned at the Lowell Observatory outside of Flagstaff, Ariz. UT is one of three university partners that will have access to the telescope for its astronomers.

The astronomers do not have to physically peer at the heavens through eyepieces and instead do their viewing on computer screens. A logical extension of this technology is that an astronomer sitting in the lab on UT’s campus could access and use the telescope in Arizona.

Beginnings

Astronomy at UT has a long and distinguished history. It has its roots in the College of Engineering where a department of engineering physics was started in 1929. Thirty-five years later it became the Department of Physics and Mathematics in the College of Arts and Sciences. Today astronomy is part of the same department in the College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics. An important addition to the department was the establishment of Ritter Observatory and Ritter Planetarium in 1967. This gave a boost to research work and provided an excellent opportunity to reach out to the community at large. Today the refurbished and re-equipped Ritter Planetarium remains a favorite place for visitors of all ages and continues to be a valuable research facility.

Over the decades, some prominent physicists and astronomers have worked in the Physics and Astronomy department at UT. They included John Turin, Armand Delsemme, Adolf Witt, Larry Curtis, Bernard Bopp, and others.

Dr. Rupali Chandar, associate professor of astronomy. At Venus looking through a special commemorative eye piece at the Discovery Channel Telescope outside Flagstaff, Ariz.

Important work

The current astronomy group at UT is relatively small but has been pursuing cutting edge research in many areas while exploring and discovering pieces of the giant jigsaw we call the universe.

The puzzle is huge. When and how was the universe created? What are its ingredients? What causes some stars and planets to die an explosive death and how does that debris get recycled to make new stars? These scientists are like archeologists who are trying to find tiny pieces of a gigantic whole, using powerful telescopes and computers as their picks and shovels.

Karen Bjorkman, the dean of the newly created College of Natural Sciences and Mathematics and previously chairman of the Department of Physics and Astronomy, is pursuing research to find and understand discs around stars, some of which provide the building blocks that form planetary systems.

Her colleague Mike Cushing, director of the Ritter Planetarium, is focusing on brown dwarfs. These are the failed stars that were never quite massive enough to ignite. They appear cold and spent and live in the shadows for a long time. Because they emit very little visible light, their presence can only be detected by using infrared light. Imagine looking for someone clad in black on a dark night. Dr. Cushing uses infrared light as his night vision glasses and has discovered quiet a few of these elusive stars.

When you meet Dr. Rupali Chandar you would never guess from her unassuming and down-to-earth demeanor that she is one of the rising bright stars in the field of astronomy. She studies galaxies to find their history and evolution. Like a forensic pathologist, she searches for fingerprints left behind by star clusters that hopefully would lead her to understand and solve the riddle of the life cycles of galaxies.

J.D. Smith, a young man with boundless energy, is virtually chasing stardust, including small organic molecules that are found in galaxies. This is often the material that is left over after the formation of new stars and also after the disintegration of old stars. It is recycling on a mammoth scale. The study of these molecules provides clues to star formation, and also to the effects caused by black holes that lurk in the centers of many galaxies.

And then there is Tom Megeath who has been using space-based infrared telescopes like the Spitzer Space Telescope and the Herschel Space Observatory, along with large ground-based telescopes in Chile and the Canary Islands, Spain, to study the formation of new stars or proto stars in the cocoons that are popularly called star nurseries. Using infrared light, he is conducting a census of these baby stars in an effort to understand the process by which stars are born.

Steve Federman, another UT researcher, is trying to understand the physics of gas and dust that fills the space between stars and hopefully solve the riddle of why there is stardust left over after the formation of stars. He is particularly interested in astro-chemistry that takes place between atoms in space as they are bombarded by the light from stars and galaxies. This gas and dust ultimately provides the material for making new stars. A useful analogy would be that of a pottery studio. He looks for leftover fragments of clay on the studio floor and tries to understand the process by which left over pieces of clay get recycled for making new pottery.

And there are theoretical physicists — map makers if you will — who do not peer through the telescopes but using known knowledge of fundamental physics, apply mathematical formulas and computational techniques for further observation and research. Jon Bjorkman is the theoretical physicist par excellence who divides his time between Toledo and Brazil to help further our knowledge of the cosmos. He and his colleagues in Brazil develop novel ways of simulating the workings of the stars within the virtual world of a computer.

Lawrence Anderson-Huang is also a theoretical physicist who specializes in understanding the atmospheres of stars by predicting the spectrum of light emitted by stars under certain physical conditions. He also has another distinction that is known to very few people inside or outside the astronomy community. He helped break new ground in determining the precise timing of Islamic holidays.

The Muslim religious calendar is based on lunar cycles. There is a time-honored tradition of determining the holy days by sighting the crescent moon. The sighting depends on eyesight and also on prevailing weather conditions. In 1984 the late Imam A.M. Khattab of the Islamic Center of Greater Toledo approached Dr. Anderson-Huang with a request to do scientific calculations of moon cycles, thus eliminating the need for visual sighting of the moon for determining the dates of holidays.

The Islamic Center was the first mosque in North America to use scientific calculations to determine religious holidays. There was much resistance to the idea by most Muslim leaders around the country who still insisted on physically sighting the moon. The collaboration of a visionary Imam and a willing scientist ushered in an era where now most Muslim communities in North America use scientific calculation to determine religious holidays.

Adolph Witt, a retired astronomer at UT, was instrumental in determining the exact direction of Mecca when the Center in Perrysburg was planned in the early 1980's.

Man has come a long way in his quest to understand the universe and through this quest have come new discoveries and new knowledge. But every small fragmentary answer raises a host of new questions. In this unending journey the later-day mariners at the University of Toledo are showing the way to a better understanding of our universe.