Owner brings heirloom seed plant back to bloom

9/9/2012

Explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark sent back collected samples of native plants to D. Landreth for cultivation. Today, most of the seeds are packaged by machine, but some of the oddly shaped ones, such as beans, need to be packed by hand.

EVENING SUN

A venture capitalist, Barbara Melera knew a thing or two about returning a business to profitability but never one so historically important as D. Landreth Seed Co. The firm, founded in 1784, has provided seeds to every president from George Washington to Franklin D. Roosevelt.

NEW FREEDOM, Pa. -- Barbara Melera pulls out a seed catalog from her trusty tote bag. On the cover is the colorful drawing of a woman in a red, Victorian-era dress, seated at a desk with an open box of seed packs. In the background is a golden valley and beneath her are large vegetables, a watermelon, carrot, radish, cucumber, and more.

The catalog, its delicate, yellowing pages filled with detailed descriptions of hundreds of varieties of seeds, dates from 1884 and was issued by the D. Landreth Seed Company of Philadelphia to mark the company's centennial anniversary.

For Ms. Melera, the catalog is a link to her company's past and a reminder of its role in America's growth.

Ms. Melera has no shortage of those reminders. She is surrounded by history.

It's there in the former canning factory in New Freedom which, since 2003, has served as home to the seed company. It's there in the machinery, the pair of still-used 70-year-old seed mixers and the 1870s-era seed packer now tucked away in a corner. And it's in the buckets, bags, and packets filled with heirloom seeds, some hard-to-find varieties that date back centuries.

It's that long history of D. Landreth Seed and its place in American horticulture that first attracted Ms. Melera to the company. Now, it binds her with a sense of obligation and determination to make sure that tradition continues.

As a venture capitalist, Ms. Melera aimed to turn around the struggling company, which by then had relocated to a warehouse in Baltimore. She had had success making other companies profitable.

But Landreth would prove different for Ms. Melera, both in its business challenge and its hold on her.

"I had never seen something as historically important as this," Ms. Melera said. "It's a company that's been in America since America began."

Founded by David Landreth in 1784, the company provided seeds to every president from George Washington through Franklin D. Roosevelt.

During their trip west, explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark sent back collected samples of native plants for cultivation by Landreth.

The company introduced zinnias and white-fleshed potatoes to America, and now provides seeds to historic gardens such as those in Williamsburg, Va.

Explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark sent back collected samples of native plants to D. Landreth for cultivation. Today, most of the seeds are packaged by machine, but some of the oddly shaped ones, such as beans, need to be packed by hand.

By the time Ms. Melera purchased Landreth it was "in a desperate situation" and on the verge of going under.

"I didn't want to see that happen," she said.

While Ms. Melera had years of personal experience as a gardener, she wasn't familiar with the intricacies of the seed business, which involves purchasing hundreds of varieties of seeds from small farmers and producers in this country and overseas.

"I was lucky. Because this company is so old it had its infrastructure in place. I just had to maintain that infrastructure and learn what it is," she said.

But there were plenty of obstacles.

What was left of the seed inventory was soiled and contaminated. The machinery needed to be replaced or repaired, Ms. Melera said.

Then there were the company's business operations. It had no Web site, no computers, no copier or fax machine. The couple of workers there still used a Smith Corona typewriter to keep accounting and customer records, Ms. Melera said.

"They kept track of customers on index cards," she said. "All of that needed to be brought into the 20th century. Forget about the 21st century, we were trying to get it into 20th century."

Ms. Melera planned to find investors to pump needed funds into the company and help with the turnaround.

"I figured if I purchased this company and cleaned it up, I could attract people to invest equity capital into it," she said. "The company needed equity capital."

But Ms. Melera found few interested in investing in a seed company that specialized in organic, heirloom seeds.

So, she and her husband, Peter, borrowed money to help update the company and replenish the shelves, and soon found themselves in a hole, particularly after the recession hit. Last year, the company was on the brink of folding as creditors sued to get their money.

An online campaign through Facebook helped raise money through the sale of catalogs and brought in donations. The catalogs, which before had been free with orders, are full of details and advice on the company's some 900-plus varieties of vegetable, flower, herb, and grass seeds.

The Facebook effort helped sell 46,000 catalogs and draw attention to the company's plight.

While the company has been tied up in court with the creditors and trying to work out payment plans, Ms. Melera said it has become profitable again. Slowly, she said, things have improved.

"We can work our way out of this situation the old-fashioned way, if people can continue buying our products," Ms. Melera said. "Financially, the company is quite healthy at this point. We can begin to pay back those creditors if we can maintain the level of business we are doing. It's expanded tremendously in the past two or three years."

Steadily, Ms. Melera has added employees -- now up to 10 -- and has rebuilt the customer base while being true to the company's historic mission of selling hard-to-find seeds for vegetables, flowers, and herbs.

In an industry where dozens of new, genetically modified varieties appear each year, Landreth has continued to concentrate on heirlooms.

"That new variety will be around two or three years and that seed company will go on to its next introduction and that seed will disappear," Ms. Melera said.

In some ways, Ms. Melera has brought the company full circle. She used a reproduction of that centennial catalog cover for the company's 2009-2011 edition, which also marked Landreth's 225th anniversary.

She also moved the company back to its home state, to a building that once served as a cannery for farmers' produce in south-central Pennsylvania. Many of those farmers had used Landreth seeds to grow their crops.

Today, trucks bring in seeds from around the globe. There are okra, onion, and lima bean seeds from the South and wildflower seeds from the Middle East.

"Almost all the zinnias that you used to purchase were grown in Colorado. Now, almost none of that takes place because water is too expensive in Colorado," explained Ms. Melera, as a warm summer breeze blew through the warehouse's open bay doors. "There is almost no flower seed grown in this country now."

A vast majority of the remaining U.S. seeds come from the Pacific Northwest, grown by small farmers who specialize in seed production.

Most of the seeds arrive at Landreth in 50-pound bags, some in smaller five and 10-pound mesh bags. They are sorted and placed in white, plastic buckets.

Shelves are lined with those buckets, whole rows devoted to various squash, tomato, pepper, and corn seeds. They run the gamut from wando peas and moon and star watermelon to pinkeye purple hull cowpeas and french breakfast radishes.

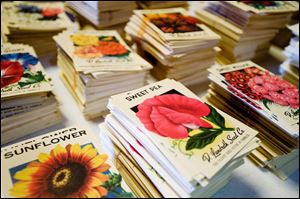

Boxes and boxes jammed with empty, pocket-sized seed packs, all with a picture of the healthy, mature product on it, sit ready to be filled.

Jim Mull operates and maintains the company's Seed Pak 2000, a fussy piece of equipment that is accurate but prone to breaking down. He uses it to fill most of the seed orders, which will really come rolling in by late fall.

Still, some of the unusually shaped seeds, such as beans, and the more expensive seeds, need to be hand-packed.

"The really expensive stuff is packed by hand," she said. "There will always be a place where they are packed by hand."

Outside, along the warehouse's long, white wall, Ms. Melera has potatoes growing in old tires. There is also asparagus, tomatoes, and dozens of other vegetables in containers, soaking up the morning sun.

It's part of Landreth's experiments to see what works best under certain conditions. There's an increased interest in container gardening, Ms. Melera said, and it's good for her and her employees to know how to advise customers.

And across the street, distinctive elephant ear plants dominate a pair of flower beds in front of a police department building. Landreth employees planted the garden with extra seeds they had this spring.

David Landreth was very patriotic and active with his community, Ms. Melera explained.

"It's important to us that we carry on that part of his legacy," she said. "To me, that is very significant. You take care of your community."