COMMENTARY

Jailhouse library jump-starts learning, dreams

5/18/2014

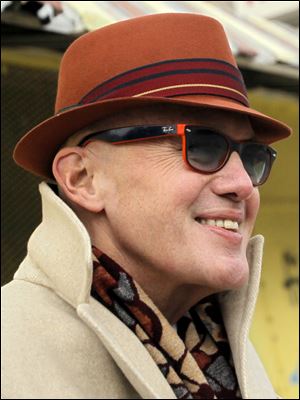

Gerritt

The Blade

Buy This Image

Gerritt

Rehabilitation is still nominally a guiding principle for corrections departments around the country. In Ohio, it’s even in the name.

But except for GED programs, prison education and rehabilitation efforts were all but wiped out in the 1980s and 1990s, as corrections departments, including the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction, quadrupled in size and became little more than warehouses. They spit out offenders who were unprepared for anything but a life of more crime.

Inmate-written prison newspapers closed. Art classes were abolished. In 1994, President Bill Clinton made prisoners ineligible to receive Pell grants for post-secondary education. School was out. Democrats such as Mr. Clinton were trying to prove they were as tough on crime as Republicans were.

But ending opportunities for growth and change behind bars wasn’t tough — it was just plain dumb. More than 95 percent of the nation’s 2 million prisoners will eventually go home. Educated prisoners, for the most part, get out of prison and stay out.

Such programs are even more limited in county jails, where most prisoners are awaiting trial and stay only a few months before they get out or transfer to a state prison. They don’t have much time to get involved in meaningful programs.

But that hasn’t stopped Lucas County Sheriff John Tharp from jump-starting a desire to learn in his nearly 500 inmates. A neat, clean, and welcoming 2,000-book library on the county jail’s second floor has inmates checking out books by authors such as Zora Neale Hurston and Alice Walker — and even writing poetry. Most of the books are donated.

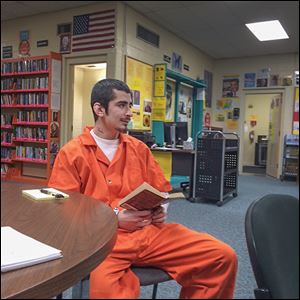

Inmate Federico Ortiz says of the Lucas County Jail’s library: ‘It feels good to come down here, check out some books, and relax.’ He wrote a poem for which he won a contest at the jail this year.

“We don’t have them long, but if we can encourage them to read, learn, and gain self-respect, it’s a step in the right direction,” Sheriff Tharp told me in the jail library. He spends an hour or so a week in the library, reading and talking to inmates and staff.

Last year, the Toledo-Lucas County Public Library ended its contract with the jail, because librarians had security concerns. Those fears were unwarranted: Librarians were behind a wooden partition, separated from the inmates they were supposed to serve. An officer was present.

It’s unfortunate that the public library wouldn’t embrace its jail contract as an opportunity to reach, through books and learning, some of the people in the community who need its services most. But it’s better that public library staff left. Librarians, or anyone else, can’t help people they fear.

Sheriff Tharp could have closed the library. Instead, he took the $75,000 a year that went to the public library contract and assigned one of his counselors to work in the jail library. He also contacted a retired University of Toledo professor he knew, Marion Boss, to help him make the library better and oversee the GED program.

They removed the wooden barrier that separated library workers from inmates, scrubbed the place, expanded hours, and rearranged the shelves to provide a more open setting. The library reopened last September, with motivational slogans and photos of historical figures such as Cesar Chavez and Nelson Mandela lining the walls.

“We didn’t want it to feel like a jail,” Ms. Boss said. “We tried to make it homelike and comfortable.”

Inmates can spend an hour a week in the library and check out two books at a time. About 300 inmates a month use the library. There’s been no theft and few disturbances.

“They enjoy the program and are respectful of it,” Deputy Sheriff Aaron Nolan, director of inmate services, told me. “They act as though it were their neighborhood library.”

Mr. Tharp sponsored a poetry contest in March that received nearly 50 entries. Federico Ortiz, 25, of Toledo, won with a poem entitled “Expiration Date,” which muses on the inevitability of death and the need to live each day as though it were your last.

“It feels good to come down here, check out some books, and relax,” he told me, dressed in an orange jumpsuit. “They’ve got a good selection of books.”

Facing a prison sentence, Mr. Ortiz is awaiting trial for aggravated burglary. “I’m bipolar and have a bad temper,” he said. “Writing poems takes me away.”

Having earned a GED, he plans to learn a trade, but he also wants to continue writing poetry and publish a book.

“I’d like to be a Shel Silverstein for kids,” he said.

Dreams can start anywhere — if they’re given a chance to grow.

A Vietnam veteran, Mr. Tharp has been a cop all his adult life, including time in the Toledo Police Department’s drug unit and gang task force. He’s tough and doesn’t tolerate nonsense, from his staff or inmates.

But he treats people with respect and understands that if the criminal justice system wants people who are locked up to change, it should offer them chances to do that. That’s not soft — it’s smart.

● Those who want to donate books, including for the jail’s law library, should contact Deputy Sheriff Aaron Nolan at 419-213-4971, or aaron.nolan@noris.org

Jeff Gerritt is deputy editorial page editor of The Blade.

Contact him at: jgerritt@theblade.com, 419-724-6467, or follow him on Twitter @jeffgerritt.