COMMENTARY

New war on poverty alters tactics and premises

8/31/2014

Why fight about the extent of blight in Toledo and how to combat it? T-Towns or a blight authority?

I say both.

Obviously both.

The city itself must be active cutting grass, clearing junk, citing slumlords. And neighborhoods have to take hold of their own destinies — they actually do a pretty good job of that in Toledo, not always getting a lot of help from the city.

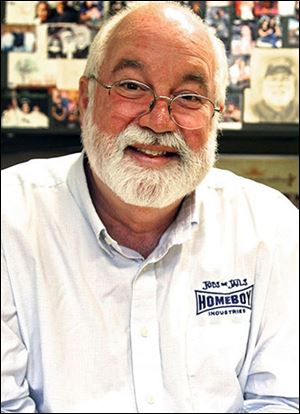

Father Boyle

But, obviously, both.

We will never have livable cities until we eliminate blight and substandard housing.

We will never have livable cities — where people want to move in, not out — until we have well-performing urban schools.

Rev. Rogers

But we will have decaying housing and kids struggling in schools so long as 20 percent of us and as many as one-fourth of our children are poor in this city.

So, we are back, ultimately, to “the war on poverty” — Lyndon Johnson and Sargent Shriver, in the 1960s. Did that war work? What have we learned about the causes and best responses to poverty? Is poverty primarily a set of habits and social norms or is it mostly a question of wealth and work distribution?

There is wide agreement today that to fight poverty you must empower and not enable or entitle. That is, you must teach a man to fish, not give him fish.

Ziraldo

And, transfer-payments work; they work better than most anti-poverty programs. The best example of a transfer payment is Social Security.

Too many anti-poverty programs simply build upon themselves, perpetuating both the culture of poverty and the poverty bureaucracy — the so called “poverty pimps” who came to do good and stayed to do well.

Under the ultimate version of this patrimonial approach to fighting poverty, every poor family would get a case worker, a life coach, a course in living skills, a rebuilt home, and a rent subsidy.

But not a job.

To escape poverty, a person needs a job.

And two more things: some kind of family and some kind of value system that lifts him up rather than degrading him.

A Catholic priest, Greg Boyle, who works with gangs in Los Angeles, says that no young man’s natural ambition is to join a gang. He joins for lack of options. So, Father Boyle created jobs by creating small businesses — starting with a bakery and then a laundry. Father Boyle’s program, he told a Toledo audience at Lourdes University a few months back, is actually two-fold: jobs and love. He creates work for young men in gangs. And he and his staff work with them, one-on-one, as the parents they never had. Jobs and family.

Simple.

But hard to put into action.

The new model of fighting poverty accepts that a family in poverty might well need intensive, across-the-board help, but insists that the family itself should design its own plan of rescue and reform.

That is what they do at Lighthouse, in Pontiac, Mich. The family in distress is the primary author of its own exit strategy.

A few weeks ago, I traveled to Pontiac in the company of former Mayor Carty Finkbeiner, civil rights leader Baldemar Velasquez, and Theresa Gabriel, a member of the Toledo City Council, to learn about what the new war on poverty looks like on the ground. The Lighthouse program is not new, but under CEO John Ziraldo it has been remaking itself. Lighthouse’s basic mission is to provide emergency housing and food. But what has become just as important to the program is independence and self-sufficiency. Mr. Ziraldo begins with the question of why, after 50 years of anti-poverty programs, there are as many poor people as ever — more poor children than at the start of LBJ’s Great Society — and the cycle of poverty, generation to generation, seems more unbreakable than ever.

He thinks it is because most anti-poverty programs have not given people the tools for independence and self-reliance. Transitional housing has meant time between lousy homes. He wants it to be a path toward stable work and a permanent home. His program, called PATH, can last as long as two years, but during that time a mom with two kids is getting specific, individualized training she wants and needs so that she graduates from Lighthouse and escapes the cul-de-sac of poverty for good.

Mr. Ziraldo has coached youth hockey for many years. In hockey, scoring is all about the set-up. A realistic approach to poverty does not just eliminate immediate crisis but sets up a person for independent living.

This is very much what Dan Rogers is about at Cherry Street Mission. What he calls the “exchange” is a bartering between the client and provider. The client gives Cherry Street his labor and gets help with everything from interviewing skills to transportation in return. He must, says Mr. Rogers, be reminded of his inherent — as well as his immediate and practical — worth. Work helps to do that. A job does that ultimately.

There is a book out called Toxic Charity, which attacks the old pitying and pat-on-the head models of help and focuses on self-renewal and respect. That the book is considered mainstream is a good sign. Thirty years ago, it was thought illiberal, if not uncompassionate, to speak of the “culture of poverty.” Edward Banfield, who first broached the subject, was called everything from a reactionary to a racist. Now it is widely admitted that the culture of poverty is key.

Part of that culture is the drug subculture.

Many people point to family disintegration and indict single motherhood, because it is admittedly tough to support a family on one salary today. But President Obama’s mother was a single mother. And he turned out pretty well. Drugs are a more tangible culprit. A cop friend told me recently that crack cocaine destroyed many an urban family a generation ago. No parenting. Any social worker will tell you the same thing. Heroin is beginning to do its damage to poor families in Toledo in 2014.

And I would site another seldom indicted culprit: pop culture. A few weeks back, Councilman Jack Ford brought together four black councilmen to talk about black-on-black violence in our city, an event that passed quickly with little notice. But together, these council members addressed the persistent message of violence that engulfs young black men in our movies and popular music. Bless the council members for their courage. For that homicidal-suicidal cultural messaging is as responsible as gangs for kids killing kids.

Is poverty a matter of culture or economics? I say both. Obviously both.

Keith C. Burris is a columnist for The Blade.

Contact him at: kburris@theblade.com or 419-724-6266.