COMMENTARY

Youngstown: A cautionary tale

10/4/2015

Downtown Youngstown skyline looking East. Once a city of 170,000 people, Youngstown has dwindled to roughly 65,000.

Third in a series

YOUNGSTOWN — As you descend, via I-80, into the Mahoning Valley, the first thought is: Wow, this land is beautiful.

It must have looked like Eden to the former Connecticut citizens who settled this part of the Western Reserve, set aside for them. Scotch-Irish came next. Welsh and Lebanese. And, eventually, African-Americans, from the South to the “free North.”

But those later immigrants came for jobs — jobs in the city. Not land. They came for steel. For Youngstown was a mighty economic giant once. It was second, perhaps only to Pittsburgh in the minds of most Americans, as a steel capital.

Once you have descended entirely into the valley, you meet the once muscular city. And it takes your breath in another way. It looks beaten. Like Rocky Balboa after the big fight he lost. Black and blue. If a city could be black and blue.

In the last 40 years, Youngstown has taken an awful beating.

In the mid to late 1970s the steel industry collapsed. Some 40,000 people lost their jobs. That was somewhere between a third and half the jobs the city had to offer. After 1979, when the last-ditch efforts of city fathers, labor leaders, and activists like Staughton Lynd collapsed and all hope of saving even one steel mill was lost, crime, domestic violence, and the shuttering of small and mid-size businesses spiked. One billion dollars in payroll was lost. And more than half the people of Youngstown moved away.

Today, a city that once held 170,000 people, and that built an infrastructure to accommodate that many people, is now comprised of roughly 65,000 people. And most did not move to the suburbs, though some did. Unlike Toledo, most of those 100,000 people went to other cities and states.

Youngstown has built a new civic center called the Covelli Centre, where a hockey team and musical acts play.

One city official told me that if you walk in any direction from downtown one-fourth of a mile, you run into severe blight.

They say what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. To a point, maybe. But Youngstown endured, in the words of longtime city Finance Director Dave Bozanich, “an economic tsunami.” Or, to return to the boxing analogy — nine rounds of constant drubbing. Only now is the city getting up off the mat.

I met Mayor John McNally, a personable and no-nonsense man who trained as a lawyer and got an advanced degree in public administration. When he was a young fellow, he thought he might like to be a city manager. He never thought he’d get into politics. He wound up doing both. The mayor in this city is very much a hands-on manager. Mr. McNally told me his is definitely not the job for a person who likes his privacy or wants to be left alone with his thoughts when shopping at the grocery store.

A legacy city

Mr. McNally was a county commissioner — a much cushier and out-of-the line-of-fire job. He was also the city’s law director. He actually wanted this job — to be the mayor of an economically devastated city. For this, I salute him. Being a mayor in a “legacy city,” particularly one that has possibly taken more hits than any other, is as hard a job as there is.

What is a legacy city? It’s a name given to once-noble rust-belt communities — like Buffalo, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Dayton, Toledo, Flint, Cincinnati, Detroit, Akron — that built the great post-World War II American economy and then suffered deindustrialization and depopulation. And, in many cases, collapse of urban infrastructure, small businesses, and schools. Note the number in Ohio.

There is an entire academic and foundation think-structure dedicated to the fate of legacy cities and how to bring them back. Alan Mallach of the Brookings Institution calls these cities America’s greatest asset and also its forgotten children.

The conventional wisdom is that Pittsburgh and Cleveland are the prime examples of the comeback of legacy cities. There are some common denominators: development of downtown areas for living as well as commerce, mostly by younger people in their 20s and early 30s. A shift to a knowledge economy — higher education, medicine, and medical research as the new drivers of urban economies. (The hospital and the university replace the steel mill and auto assembly plant.) And development of waterfronts. “Water is magic,” said one urban planner I spoke with.

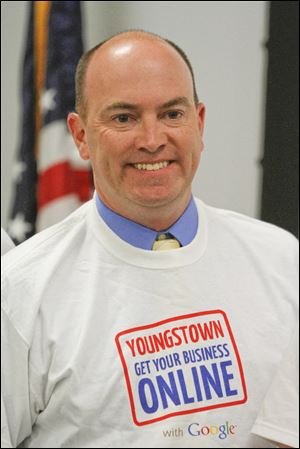

In partnership with Google, mayor John McNally will announce a new initiative for Youngstown businesses to ÒGet Your Business OnlineÓ at an 11 a.m. press conference at the Youngstown Business Incubator.

It’s tougher for the smaller legacy cities, especially ones without great private or foundation wealth. And particularly when there are no longer major corporate headquarters present. Youngstown was hit even harder with the loss of steel than Detroit was by the loss of much of the auto industry, and the scale is much smaller so the hit has more reverberations. And the recovery is taking longer.

Stop the bleeding

Once a month, Mayor McNally holds “five minutes with the mayor,” when anyone can come see him about anything. (But they really have to leave after five minutes.) He told me that when people tell him, as they often do, that he has to bring new people to town, he agrees. Of course. Easier said than done, maybe. But first he has to stop people from leaving — stop the bleeding.

That, Mayor McNally said, is what several of his predecessors tried to do, and with some success. Jay Williams went on to become President Obama’s car czar, and he is now his chief economic development officer. Mayor McNally told me that as mayor he has to simultaneously manage decline and expansion. He spends much of his time trying to figure out which buildings in the city need to be razed, which streets shut down and homeowners moved, and which brownfields can be turned to green. And, how to get the grass cut in blighted areas. With more than half of what was once the city gone, the city has to be “right-sized.” Not a fun job. Or a process any mayor would relish. But it’s the reality. It’s Detroit’s reality. It’s Youngstown’s. Toledo, take heed.

At the same time, Youngstown is developing urban parks and downtown housing for the young — and every new condo and apartment project is full. Youngstown wants to develop its riverfront. It has built a new civic center — the Covelli Center — where the local hockey team and visiting rock groups play. And though the city had to borrow to build it, it is making money.

‘A college town’

Youngstown is also now calling itself “a college town.” Youngstown State University is a handsome campus — anchored by the Butler Museum of American Art and the historic St. John’s Episcopal Church. This strategy is not only smart — it’s a nice and buzzing part of town — but necessary. The knowledge economy is the way forward.

People in Youngstown are very happy about Jim Tressel coming to town to be president of Youngstown State, where he once coached football. He has formed a good working partnership with the mayor. He’s the future, not the past.

The creativity economy can and must flow from the knowledge economy — things like solar power, which is THE thriving industry in Buffalo now and which already has a strong foothold in greater Toledo in First Solar.

When I say “Toledo take heed,” I mean this: No one saw that steel was not forever. The collapse for Youngstown seemed to come suddenly out of nowhere — like the proverbial tsunami. We in Toledo need to think about the fact that cars are not the only things we can make here. Jeep is not forever. The cities that diversify are the ones that survive. And sometimes thrive. We need to diversify our economy: Other car companies. Other types of cars — electric. Other manufacturing products. Other industries — based on knowledge and creativity.

Youngstown is up off the mat now, with help from some heroic people and, as with our own city, young folks who don’t buy into the tired old negativity of people who have seen too much. God bless the optimists for their spirit and pluck. Negativity can cripple a city trying to fly again.

But Youngstown now has to almost totally rebuild itself. The problems of the city — economic, cultural, political, and habitual — have grown deep and strong roots. Mayor McNally and the county auditor have been indicted by the state of Ohio for alleged past corruption on the county level — 25 felony and nine misdemeanor counts in Mr. McNally’s case.

Lessons for Toledo

Every American is entitled to the presumption of innocence. And even police officers, fire chiefs, and politicians are protected by the Constitution. I liked the mayor and hope he is innocent. But we in Toledo do not want to go there. We do not want to be, in 10 years, a city concerned mostly with closing streets and sewer lines and wondering which local leader will be indicted next.

And if we do not restore some balance to our economy and our politics -- some economic diversity and some government professionalism (more on this next week) -- this could happen.

Balance.

Though Youngstown was always smaller as a city than Toledo, the greater metropolitan area is similar in size to our own — about 600,000 people.

We are not immune if we put all our eggs in one basket.

And we have assets. The Mud Hens. The museum. The zoo. The parks and library system. The people. And that magic ingredient — water. If we protect and monetize that precious asset.

That doesn’t mean we should stop making things or wanting to make them. Youngstown was probably saved by the GM Lordstown plant, which once made the Chevy Vega, one of the worst small cars ever made, and now makes the Chevy Cruze, one of the best small cars ever made.

In today’s world, we must be able to make what we make well. But we must also be able to make many things.

Paul Newman was an Ohioan who reversed the migration pattern and went to Connecticut to live. He became that state’s greatest philanthropist. He made a fortune in pasta sauces and salad dressings and used it to help thousands of people — especially kids sick with cancer at his Hole in the Wall Gang Camp. Asked, when he turned 80, what the secret to his life and his successes had been, he said: “Luck.” It was an honest and humble answer. You have to have some luck in life.

So too with cities. To thrive, cities need a little luck. But also positive mojo. The key is not to envy the other guy’s luck but to take the luck you have and make more of it.

Keith C. Burris is a columnist for The Blade. Contact him at: kburris@theblade.com or 419-724-6266.