Long-term strategy in methadone use

9/22/2003

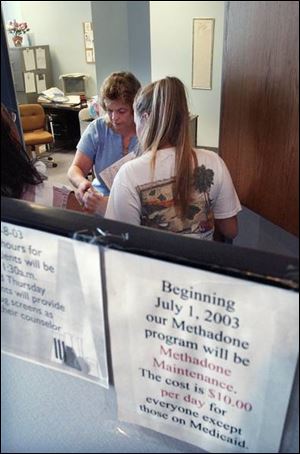

Substance Abuse Services, Inc., clients once were cut off from methadone after a year but now can stay on the drug indefinitely. Kathi Ross works in the Adams Street office.

Ross Chaban is blunt when he talks about his previous thinking that most heroin addicts don't need lifelong methadone medication to prevent them from abusing heroin.

“I was an idiot,” Mr. Chaban said.

It's not an easy admission for the executive director of Toledo-based Substance Abuse Services, Inc., northwest Ohio's only methadone clinic for heroin addicts. But it was clear that Toledo's strategy for treating addicts dependent on heroin, Oxycontin, and other opiates was not working.

After a year or so of treatment, all addicts were cut off from methadone, leading many to abuse drugs again or seek treatment elsewhere.

So, on July 1, SASI switched to methadone “maintenance” to treat heroin abusers - making Toledo the last of Ohio's nine methadone clinics to switch to this treatment approach. Addicts can now stay on methadone for as long as they need.

The change, while in line with the rest of the state's clinics and nationwide standards, is still controversial.

Some critics believe all addicts should be weaned off methadone.

“Tony,” however, is grateful for the change in SASI's treatment approach.

A quick-talking man in his 40s with a firm handshake, a wife, and a child, he is proud of his successful career as a foreman for a Toledo transportation company.

He is also a former heroin user.

He abused the drug for five years during his youth and eventually turned to methadone to pull out of what he said was a downward spiral of depression, sickness, and drug abuse. He would skip work and spend entire days chasing a heroin high.

“I believe it saved my life,” Tony said of methadone.

Tony, a SASI client, asked that his real name not be used because he feared how friends and co-workers might react. He was put in contact with The Blade through SASI officials, who verified his treatment and related information.

Methadone, a federally approved medication, has been used to treat heroin addiction for decades. A synthetic narcotic, methadone is usually swallowed in liquid form. It does not produce a “high” like heroin, but does prevent the cravings of heroin addicts. It is also used to treat other opiate addictions, including abuse of narcotic painkillers such as Oxycontin or Dilaudid.

Tony had been on methadone treatment in another state before moving to Toledo a few years ago. He was nearing the mandatory cutoff for methadone treatment at SASI this summer and was contemplating traveling to Detroit for it until SASI switched to a maintenance program. Regular use of methadone is invaluable for addicts, he said.

“I've been able to lead a normal life,” he said.

SASI's change in methadone treatment came after the organization merged with another drug-treatment agency, Comprehensive Addiction Services, where Mr. Chaban is also executive director.

Mr. Chaban said the statistics alone showed a need for change.

Drug abuse involving heroin, Oxycontin, and other opiates is climbing state and nationwide. In just two years, from 2000 through last year, the number of heroin addicts seeking help at Ohio methadone clinics jumped 42 percent to 6,878 patients, according to state drug-treatment officials.

But while abuse rates were growing, the number of people seeking methadone treatment in Toledo had fallen to approximately 40 annually from a high of about 250 in previous years. Akron, a city similar in size to Toledo but with a different treatment strategy, has almost 400 people per year receiving regular methadone treatment.

Cutting addicts off of methadone after a year or so of methadone treatment just did not work, Mr. Chaban said of SASI's approach.

“It was a complete failure,” he said. “It's like telling a diabetic taking insulin you don't need insulin any more and you can eat Twinkies.”

Many local addicts began abusing heroin again, which often led to them getting in trouble with the law, losing their jobs, or causing problems for their families, he said. Some addicts traveled to clinics elsewhere for methadone. Mr. Chaban estimated 150 or more former SASI patients traveled to Detroit for methadone.

Still, he was not surprised at SASI's previous resistance to methadone maintenance given that even he used to feel that way.

Some in the criminal justice system and drug-treatment field likewise continue to view methadone with suspicion. Critics believe that methadone, if it is used at all, should be used onlyfor short-term, “detox” use. Using methadone long-term just substitutes one addictive narcotic for another, they argue.

In fact, the former director of Ohio's Department of Alcohol and Drug Addiction Services, which certifies the state's methadone clinics, did not believe in methadone maintenance, said Mr. Chaban and other drug-treatment officials in the state.

“The leadership at the state was resistant to the concept [of long-term methadone use],” said Ted Zigler, chief executive officer of Community Health Center in Akron, which SASI has now modeled its methadone program after. “But, in fact, 45 years of research and science have demonstrated that methadone maintenance is the single most successful treatment of narcotic addiction on the face of the earth.”

Officials with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the federal agency that oversees methadone clinics, said Mr. Chaban and Mr. Zigler are smart to use long-term methadone treatment methods.

Robert Lubran, director of the division of pharmacological therapies at the agency, said methadone maintenance is usually the best option for heroin addicts, and detox-only strategies “are much less effective.” Mr. Lubran said the relapse rate in detoxification-only programs is so high it's almost “wasteful” to try it.

Stacey Frohnapfel, spokesman for Ohio's Department of Alcohol and Drug Addiction Services, disputed that the state or the department's former leader, who left in July, opposed methadone maintenance.

While the state supports methadone maintenance, Ms. Frohnapfel said the department maintained - and still maintains - that only a small percentage of heroin addicts will always need methadone treatment.

“For the majority of heroin users, it's possible to become drug-free,” she said.

Mr. Zigler said that is not true, at least for those who have abused heroin long enough to become addicted. He said while many heroin addicts won't need methadone for life, most need to be on it at least two years, many for years longer, or permanently.

Dr. Gerry Steiner, SASI's newly hired medical director, said nationally only 10 to 20 percent of heroin addicts can be weaned off methadone.

Dr. Steiner said scientists today have a much better understanding of opiate addiction than in years past. Heroin, if used extensively, damages the brain and overloads the body's natural opiate system.

The body has its own pleasure reward system that includes natural opiates such as endorphins. These chemicals help regulate everything, from hunger and thirst to stress and immune function. Heroin can damage that natural system permanently and cause a host of problems, including drug cravings, Dr. Steiner said. Methadone helps bring the body's opiate system back in balance.

“Methadone is medicine. It helps break the cycle of trying to chase highs,” he said.

Mr. Zigler said he likes to refer to methadone treatment as “turning tax liabilities into tax assets” to convince those concerned about the cost that treatment makes sense. Dr. Steiner agreed, saying the $10 daily cost for methadone - which is covered by clients, Medicaid, or insurance - is much cheaper than the financial costs associated with drug abuse and drug-related crime.

But beyond the financial savings, Mr. Zigler said methadone maintenance is humane for the addicts and their families.

“People who aren't treated are buying drugs on the street, stealing stuff, or prostituting,” he said. “We're giving people a chance to get their life back.”