Superman gets credit for spinal research role

2/7/2004

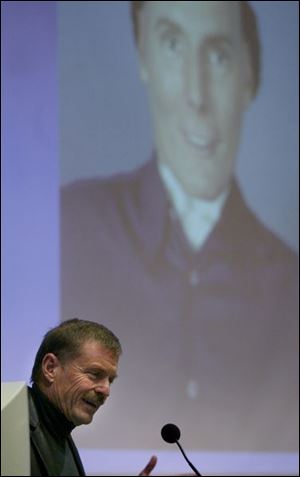

Dr. Oswald Steward praises actor Christopher Reeve, shown in background, for his involvement in the field.

Dr. Oswald Steward gestures toward the giant face projected on the screen behind him. “The field of spinal cord injury has been turned on its head by this man,” he says.

The nearly 100 neuroscientists and students clustered in a lecture hall at the Medical College of Ohio look into the glowing image of Christopher Reeve - Superman. It s an unusual moment for a scientific meeting, 60 seconds absent of the mind-numbing charts of data, the miles of graphs, the multicolor circles, ovals, and squares that attempt to reduce incredible complexities to Colorforms.

Dr. Steward praised the actor s involvement in spinal cord studies. “It s affected my research in the sense that every day I walk in the lab and ask, what I m doing today? Is that something I can think about moving to the clinic? Normally it s what is the next cool experiment?

Dr. Steward is director of the Reeve-Irvine Research Center at the University of California at Irvine. He was the keynote speaker yesterday at the Annual Neurobiology Research Day, sponsored by MCO.

The Reeve-Irvine center is named for the actor and the philanthropist who founded it, Joan Irvine Smith. It s closely allied with the Christopher Reeve Paralysis Foundation.

New Yorker magazine called the injured actor s impact on the field of spinal cord injury “the Reeve effect.” After he suffered a broken neck in an equestrian contest in Virginia, he challenged the established view that spinal cord injuries were irreversible. He backed it up with research funding.

“What Christopher Reeve has done is create a culture of action,” Dr. Steward said.

The most encouraging research results have to do with treating spinal cord injuries immediately after they occur.

A spinal cord injury isn t a single event. It s a biological process. It starts with discreet damage to a specific portion of the body s main nerve highway, and progresses over days and weeks, growing larger and more devastating. Finally, the small injury is a big hole.

“Over the last decade, we ve seen little effect or improvement. Now, we wonder, is it really worth it, or should we back off?”

Human trials on the compound are expected, but the first patients probably will be arthritis sufferers, Dr. Steward said.

In fact, the treatment of spinal cord injury will not be a big profit-maker, he said. Perhaps 300,000 people have such injuries nationwide. What may keep venture capital dollars flowing is hope that drugs to treat spinal cord injuries also might help other neurological conditions, such as stroke.

Another area of investigation uses human embryonic stem cells to regenerate myelin, the protective coating nerves need to function. Myelin loss occurs as an acute injury becomes chronic. So far, experimental treatments show no improvement of function for animals with long-standing spinal injury, Dr. Steward said.