North America on high alert for signs of avian flu migration

11/20/2005

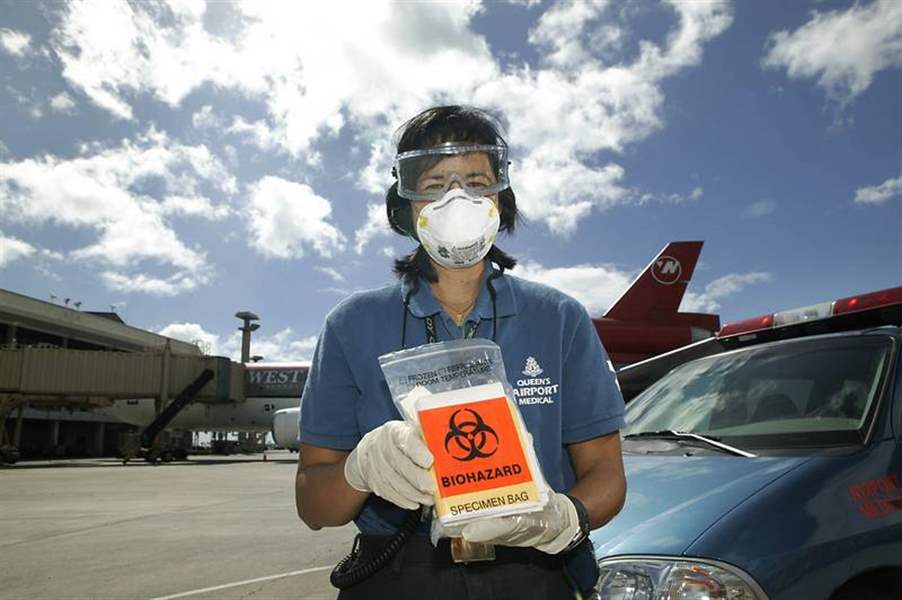

Belinda Lee holds a specimen bag that Hawaii uses to check ill airline passengers for bird flu. Hawaii is the first state to test.

Dr. Walter Boyce, left, and Grace Lee of the University of California, Davis, check a magpie for avian flu. They are part of a large network of federal, state, and private industry groups doing extensive monitoring and surveillance along the major migratory flyways.

Fears over the "Asian bird flu" spreading to North America via migrating birds has wildlife and poultry experts keeping a close eye out for any signs of the virus.

A deadly strain of avian influenza virus is wreaking havoc in poultry across Asia, recently spreading to China, and is known to have infected by direct contact with poultry nearly 130 humans, killing at least 67 of them. World health authorities fear that an eventual mutation in this virus could result in human-to-human transmission, triggering a global epidemic capable of killing millions of people.

While the bird flu hasn't been confirmed in North America yet, wildlife and poultry authorities here are concerned because of several possible pathways for bringing the virus here via migratory birds, especially through the Alaska-Siberia transcontinental corridor. Wild birds infected with the virus could end up infecting domestic birds, such as chickens or turkeys.

"There's a lot of interchange in the Bering Sea region, said Kenn Kaufman, an internationally recognized naturalist, birding authority, and author of a series of field guides.

"That's where there's a lot of crossover, so that birds nesting in Alaska may winter in southern Asia, Africa, even Australia; while birds nesting in Siberia may winter in the southern U.S. or Mexico, such as some sandhill cranes, or even South America, such as gray-cheeked thrush or pectoral sandpiper."

Mr. Kaufman, who recently moved to the Oak Harbor area, was invited last year to lecture in Europe on bird migrations. He's also working on a book on the subject and helped compile a generalized global migration map.

"Here in Ohio we get a lot of birds that are undoubtedly on their way to or from Alaska," he added.

Protecting human health from a deadly flu epidemic, of course, is the uppermost long-term concern. But close behind it is protection of the domestic poultry industry, upon which so many North Americans rely for food.

That industry has a retail market value worth $50 billion annually - just for chicken, not counting the eggs or turkeys. Some 9.5 billion chickens and more than 250 million turkeys are slaughtered for food annually in the United States.

Untold millions of migratory birds - ducks, geese, gulls, terns, sandpipers, songbirds, and more - stream down from their northern North America summering grounds during fall movement to wintering grounds, some as distant as Central America and South America.

That corridor is considered the most likely migratory path, should wild birds contract the deadly virus and survive to bring it to North America. As a result, a loose coalition of state and federal wildlife authorities is monitoring bird populations.

Belinda Lee holds a specimen bag that Hawaii uses to check ill airline passengers for bird flu. Hawaii is the first state to test.

"We put out a pretty big net [this year] and did not find any H5N1," said Nicholas Throckmorton, a spokesman for the Fish & Wildlife Service, part of a network of federal, state, and private industry organizations cooperating in an extensive, already well-established monitoring and surveillance program.

The H5N1 virus is a specific strain of Type A avian influenza, one that is particularly deadly. This strain has been present in Asia since 1997 and is ravaging domestic poultry populations there, principally chickens and domestic ducks.

But lest such news create unrealistic fears of wild birds or even instigate a decline in dining on domestic poultry, authorities note the following:

"We're having turkey at the Slemons house this Thanksgiving, and we might have wild duck if I get lucky and have a good hunt," assures Dr. Richard Slemons, an Ohio State University veterinarian and widely known authority on avian influenza.

Dr. Slemons said, contrary to some reports, that there are some forms of H5N1 already present in wild, free-ranging birds in North America, but they're low-pathogenic strains.

He's been sampling hunter-bagged waterfowl along the south shore of Lake Erie for more than 30 years and has found that about 5 percent of wildfowl are shedding a low-pathogenic Type A virus in their feces. "The strains of avian influenza virus have never been known to present a problem to humans," he said. "They have not caused hunters, or anybody, problems in North America or around the world."

But particular Asian strains of high pathogenic H5N1 are getting so much attention, Dr. Slemons suggests, because "they are unusual.

"It behooves us to prevent those viruses, or their genes, from getting into the Western Hemisphere. And if they are introduced we need a very good surveillance system for early detection." That infrastructure is already in place, he adds.

"In the United States, Canada, England [among other western poultry producers], there is a big safety margin provided by the extensive infrastructure to detect [such a virus]." With poultry, "a sick bird does not make you money," Dr. Slemons said. "So the producers must keep their birds healthy."

Also, poultry in the United States are not routinely vaccinated for avian influenza. So if the virulent strain of high pathogenic H5N1 Asian virus turned up here "we would find it very quickly. And appropriate action would be taken immediately to eradicate the virus.

"We're not sure what's going on with wild birds in Asia now," the OSU researcher added. "The way it's moving around would suggest that wild [migratory] birds could be involved. But it's not been proven."

Migratory birds, however, remain suspects in carrying the virus from eastern Asia to Russian, Turkey, and Croatia, among other Eurasian locales.

"If it kills wild birds, [then] dead birds don't travel very far," Dr. Slemons said. "So it would have to infect a migratory bird without killing it or even making it sick." Then the carrier would have to somehow spread the virus to a susceptible species.

Waterfowl and shorebirds head the list of usual suspects among bird groups. They are listed by a USGS field manual of wildlife diseases as frequent carriers of avian influenza strains. Gulls and terns are "almost usual suspects," said Bruce Woods, a spokesman for the USF&WS in Anchorage, Alaska. Maritime birds, upland gamebirds, and ratites [ostrich family] are listed as occasional transmitters.

The human infections in Asia, related to proximity and handling of infected poultry show a "far bigger jump" - from poultry to humans - than the jump would be from wild bird to domestic bird, Dr. Slemons said. But looked at in perspective, about 130 human cases, half of them fatal, while obviously disconcerting, "[are] not very many infections," Dr. Slemons noted, especially considering the number of exposures across eight years.

However, the longer the deadly virus strain is allowed to persist in domestic Asian poultry, the greater the chances of a mutation to a virus that can be more efficiently transmitted human-to-human, which could emerge in a pandemic form.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has released a three-year $5 million grant for 24 groups in 14 states, all focused on prevention and control of avian influenza in U.S. domestic poultry. It was the largest single disease grant on record from the USDA, Dr. Slemons noted, though it was not driven by the Asia outbreak.

Paul Slota, a branch chief in the USGS Center in Madison, said with migratory birds, the focus will be on next spring's northward migration and remixing of transcontinental species. He said there's not enough data to know if migratory birds are involved. Another scientist, George Happ, a research professor at the University of Alaska-Fairbanks, heads up a group in cooperation with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game that is conducting additional sampling of migratory birds, with samples being screened by the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in Bethesda, Md. He is also working with OSU's Dr. Slemons.

"We've collected 4,500 swabs," he added. "We've screened 500 birds from last summer, and of those, 10 percent have avian influenza but not H5N1."

The sampling, he said, will continue in 2006. An attempt is under way, pending sufficient funding, to assemble the Alaska Avian Influenza Collaborative, a coalition of federal and state wildlife and health agencies.

Professor Happ keeps the issue in perspective. "You can get hit by a meteor. There's a chance. But it's pretty damn small."

Contact Steve Pollick at: spollick@theblade.com or 419-724-6068.