Simpler CPR: Drop the mouth-to-mouth

4/1/2008

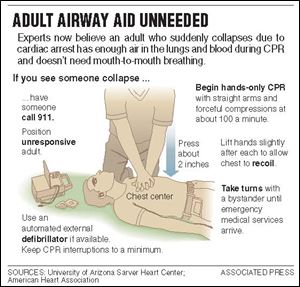

NEW YORK - You can skip the mouth-to-mouth breathing and just press on the chest to save a life.

In a major change, the American Heart Association said yesterday that hands-only CPR - rapid presses on the victim's chest until help arrives - works just as well as standard CPR for sudden cardiac arrest in adults.

Experts hope bystanders will now be more willing to jump in and help if they see someone suddenly collapse. Hands-only CPR is simpler and easier to remember and removes a big barrier for people skittish about the mouth-to-mouth breathing.

"You only have to do two things. Call 911 and push hard and fast on the middle of the person's chest," said Dr. Michael Sayre, an emergency medicine professor at Ohio State University who headed the committee that made the recommendation.

Dr. Sayre said the ideal would be 100 pushes a minute with enough force to make the chest go down 2 inches, but, he added, "there is no need to use a metronome and a ruler."

The chest presses should continue until paramedics take over or an automated external defibrillator is available to restore a normal heart rhythm.

This action should be taken only for adults who unexpectedly collapse, stop breathing, and are unresponsive.

The odds are that the person is having cardiac arrest - the heart suddenly stops - which can occur after a heart attack or be caused by other heart problems. In such a case, the victim still has ample air in the lungs and blood, and compressions keep blood flowing to the brain, heart, and other organs.

A child who collapses is more likely to have primarily breathing problems - and in that case, mouth-to-mouth breathing should be used. That also applies to adults who suffer lack of oxygen from a near-drowning, drug overdose, or carbon monoxide poisoning. In these cases, people need mouth-to-mouth to get air into their lungs and bloodstream.

But in either case, "Something is better than nothing," Mr. Sayre said.

The CPR guidelines had been inching toward compression-only. The last update, in 2005, put more emphasis on chest pushes by alternating 30 presses with two quick breaths; those "unable or unwilling" to do the breaths could do presses alone.

Now the heart association has given equal standing to hands-only CPR. Those who have been trained in traditional cardiopulmonary resuscitation can still opt to use it.

Mr. Sayre said the association took the unusual step of making the changes now - the next update was not due until 2010 - because three studies last year showed hands-only was as good as traditional CPR.

An estimated 310,000 Americans die each year of cardiac arrest outside hospitals or in emergency rooms. Only about 6 percent of those who are stricken outside a hospital survive, although rates vary by location. People who quickly get CPR while awaiting medical treatment have double or triple the chance of surviving. But fewer than a third of victims get this essential help.

Dr. Gordon Ewy, who has been pushing for hands-only CPR for 15 years, said he was "dancing in the streets" over the heart association's change. Dr. Ewy is director of the University of Arizona Sarver Heart Center in Tucson, where the compression-only technique was pioneered.

Dr. Ewy said there is no point to giving early breaths in the case of sudden cardiac arrest, and it takes too long to stop compressions to give two breaths - 16 seconds for the average person.

Rescuers performing traditional CPR also take longer to start than those who use hands only, maybe because it takes more time to prepare - intellectually and emotionally - for the more complex and intimate procedure.

Anonymous surveys show that people are reluctant to do mouth-to-mouth, Dr. Ewy said, partly because of fear of infections.

CPR-trained bystanders also cite panic and fear of causing further harm as reasons for inaction. Such fears are unwarranted. "If you do nothing, the person will die," Dr. Sayre said. "And you can't make them worse than dead."

In recent years, emergency service dispatchers have been coaching callers in hands-only CPR rather than telling them how to alternate breaths and compressions.

"They love it. It's less complicated, and the outcomes are better," said Dallas emergency medical services chief Dr. Paul Pepe.