NOT WHAT THE DOCTOR ORDERED

Patients suffer as care, coverage limits collide

Physicians say insurers intrude on treatment

8/24/2008

Dr. Joe Assenmacher of Toledo says he s become frustrated by doing battle with insurance companies. On a daily basis I have to change what I do because of insurance companies telling me what I can and cannot do, he says. It s all about money. That s what it is.

The Blade/Jeremy Wadsworth

Buy This Image

The first in a four-part series

Beverly Sue Dunbar of Ashland, Ohio, has encountered insurance-related problems obtaining medication for her daughter, Sarah, who struggles with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder.

When a patient steps into a doctor's office, he trusts that the only thing on his physician's mind is how to make him better.

But physicians across the United States fear that increasingly stringent insurance rules and the frequent second-guessing of doctors orders are eroding the doctor-patient relationship.

A Blade investigation, including interviews with about 100 physicians and a national survey of doctors with more than 900 responses, revealed that a growing number of doctors believe there's an epidemic of insurers dictating medical-treatment decisions.

Increasing health-care costs and an influx of expensive drugs and tests, combined with an aging population, set off a health-care crisis in the United States.

Contending with soaring costs, insurers changed the business of health care by requiring preauthorizations, mandating cheaper drugs, and tightening controls on treatment decisions.

But among the first casualties of these changes, many physicians said, was the doctor-patient relationship.

Doctors accept some blame for the nation's health-care predicament, acknowledging they failed to police the use of expensive medical resources and rein in costs for health care, which ballooned to a $2.4-trillion-a-year industry in the United States. Although doctors acknowledge their role in the crisis historically over-using tests and over-prescribing medication, sometimes because of concerns about being sued they contend a harsh backlash from insurers has put their patients and their practices in jeopardy.

READ THE SERIES: Not What The Doctor Ordered

'The decision-making of the physician is being challenged and compromised on a daily basis,' said Dr. Warren Muth, a general surgeon in Dayton for 31 years and president of the Ohio State Medical Association. 'We are trying to take care of people. Get out of our way.'

Insurers said they aren't intruding but striving to efficiently manage the costs of covering health care for millions of people, many of whom get coverage through their employers. Insurers must balance the needs of patients with the budgetary constraints of businesses that pay for coverage.

'[Employers] want high-quality services, they want safe services for their employees, but they also want them in a cost-effective manner,' said John Randolph, president of Paramount Health Care in Maumee, the insurance arm of Toledo's ProMedica Health System.

Dr. Brad Olson treats many young Medicaid patients, such as Sarah, who have mental health and behavior disorders. When those children are denied their prescribed medication, the physician says, trouble often sets in.

Delays and denials

The Blade's eight-month investigation captured the stories of physicians in rural and urban areas, those in solo and group practices, specialists and primary-care practitioners, and physicians in private practice and those who work for health-care systems. Some were members of physican associations; some were not.

Doctor after doctor expressed the same worries that their clinical decisions are increasingly overruled by insurers, at times harming patients.

The delays and denials affect all types of patients in a multitude of ways, doctors say from grade-school children who terrorize classmates when insurance won't pay for their behavior medication to a man who waited weeks to learn whether he would be covered for a second opinion on a potentially life-saving kidney-liver transplant.

'It is just terrible, and I don't know what to do,' said Linda Dull, the mother of Gunner Dull, an 11-year-old boy in Ashland, Ohio, who has struggled to get his Medicaid insurer, Buckeye Community Health Plan, to pay for the behavior medications prescribed by his doctor.

'We go around with Buckeye. We go around with the drugstore. It's expensive, and we don't have the money,' Mrs. Dull said.

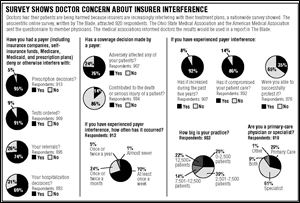

The results of The Blade's online survey of members of the Ohio State Medical Association and the American Medical Association showed that 99 percent of the 920 respondents reported interference by insurers in their treatment of patients.

The survey, which was sent by the associations to their members and included 700 Ohio respondents, questioned doctors and doctors' offices about interference from insurance companies, self-insurance funds, Medicare, Medicaid, and prescription drug plans. The survey, which was not scientific, showed:

- Ninety-five percent of respondents said insurers interfered with decisions about prescriptions, 91 percent with testing, 74 percent with referrals, and 69 percent with hospitalization decisions.

- Eighty-six percent said interference compromised patient care, 76 percent said it adversely affected their patients, and 65 percent said they were unable to successfully protest denials.

- Seventy percent noted they experience interference at least once a week, with 92 percent answering that interference increased during the past five years.

- Fourteen percent believed interference from an insurer had contributed to the death or serious injury of a patient.

A political issue

'I am deeply troubled by The Blade's report of how insurance companies, not doctors and nurses, are making decisions about patient care,' said Sen. Barack Obama, the presumptive Democratic nominee for president, in a statement to The Blade. 'Medical decisions should be made based on what's good for your health, not what's good for an insurance company's bottom line.'

His Republican opponent, Sen. John McCain, told The Blade last week in a statement that he wanted to strengthen the doctor-patient relationship.

'My reforms will place a premium on getting away from expensive and unconnected visits to multiple providers and moving to having the doctor coordinate care for patients, with an emphasis on wellness, prevention, and the treatment of chronic disease,' Mr. McCain said.

A matter of oversight

Doctors want to be autonomous in their decision making, which insurers said helps explain physicians' perception that insurers are interfering.

'They don't really like it when we ask questions about what they're doing,' said Kelly McGivern, president and chief executive of the Ohio Association of Health Plans.

Insurers say oversight is necessary, and they employ doctors to review claims and help set medical treatment guidelines. Appeals processes are available when agreements can't be reached.

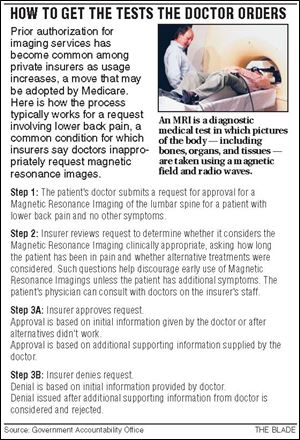

As doctors order more tests, procedures, and expensive medications, insurers are increasingly mandating preauthorization to control rising costs for businesses.

'[Employers] pay the bills and they write the check, so they have the discretion,' said Dr. Robert Rzewnicki, chief medical officer of Medical Mutual of Ohio, the state's third-largest health-insurance provider.

He said only about half of doctors are in the American Medical Association and the Ohio State Medical Association, and they primarily join because they are interested in lobbying for changes.

'You are definitely looking at a subset' of physicians, said Dr. Rzewnicki, a rheumatologist who continues to practice.

The profit factor

Insurers are in business to make a profit. Last year the nation's largest insurer, UnitedHealth Group Inc., made $4.7 billion, with its president and chief executive, Stephen Hemsley, receiving $13 million in total compensation.

Physicians say that the drive for profits is partially to blame for the tension between doctors and insurers.

'Insurers have been trying to practice medicine from an economic standpoint, and what we are finding is that what we think is the best thing for the patient isn't the best thing for the insurance company monetarily, and therefore it gets nixed right off the bat,' said Dr. Marc Saunders, a Warren, Ohio, surgeon.

Dr. Robert Jandl, an internal medicine physician in North Adams, Mass., said he feels like a midlevel bureaucrat for insurance companies.

'There are so many ways in which we are either coerced or recruited to deal with medication issues or preapproval for testing,' said Dr. Jandl, who chafes at sending his patients to specialists he views as inadequate when there are physicians he trusts available but not in network.

'I think it is just a deeply offensive place to dwell,' Dr. Jandl said. 'And it is dispiriting to the profession because it has no value to the patient's care and that's what you are there for.'

We do care'

Minnesota-based UnitedHealth has specific guidelines governing what it will and will not cover, said Dr. Dick Justman, the company's national medical director.

For example, the insurer does not pay for cosmetic and experimental treatments, Dr. Justman said, although it routinely reviews the latest studies and adjusts guidelines.

UnitedHealth generally doesn't require preauthorizations but keeps costs down by monitoring doctors who order higher rates of tests and procedures.

The company doesn't want to deny patients medically necessary treatments, but it does have an obligation to employers to make sure all care is appropriate, Dr. Justman said.

'We do care, and it does matter,' he said. 'We try not to get in between the physician and the patient.'

Gunner Dull, 11, and his father, Randy Dull, meet with Dr. Brad Olson during a visit to the Ashland, Ohio, physician s office. The Dulls struggled to get their Medicaid insurer, Buckeye Community Health Plan, to pay for behavior medications for Gunner, who has Asperger s syndrome, a form of high-functioning autism, and attention defi cit hyperactivity disorder.

Effects on patients

When 9-year-old Sarah Dunbar couldn't get her medication, her grades dropped, she got into fights with other kids, became depressed, and had trouble sleeping. Sarah's struggles with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder became so out of control that neighbors threatened to call police.

Gunner Dull has good spells and bad but suffers setbacks when he can't get his medication. The 11-year-old baseball player and budding artist suffers from

Asperger's syndrome, a form of high-functioning autism, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Isaac Baker, a 7-year-old with Tourette's syndrome and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, no longer has tics and experiences less anxiety with help from his medication. He's able to stay overnight with his grandmother, something he feared without the help of his medication.

Sarah, Gunner, and Isaac are all treated by Dr. Brad Olson, a pediatrician in Ashland, Ohio. And all three children among several other Medicaid patients treated by Dr. Olson have encountered trouble obtaining the medications prescribed for them because of denials by Buckeye Community Health Plan, which manages the care of many Medicaid patients in Ohio.

Sarah Dunbar's mother, Beverly Sue Dunbar, said that when her daughter doesn't have her medication, she becomes violent, slams doors, and threatens to kill herself. She was nearly arrested for fighting with other children, her mother said.

'But with the medication, she isn't like that,' Ms. Dunbar told The Blade.

Physician frustrations

Like many physicians, Dr. Olson is frustrated by the increasingly aggressive tactics used by insurance and pharmacy plans to deny or change prescriptions written by doctors. His practice, which is made up mostly of Medicaid patients, includes many children with mental health and behavior disorders.

'I've got kids who are getting kicked out of preschool, who are biting their sisters, who are suicidal, who are homicidal. I take care of a lot of those kids,' said Dr. Olson, who practices alongside his wife, Dr. Colleen Olson, also a pediatrician, as well as social workers, psychologists, and a child psychiatrist.

'There are some medicines whether they are treating symptoms or illnesses that can control a lot of this behavior,' he said.

Insurers, though, often will only pay for certain medications or for specific dosing regimens, even if the patient needs more or less of a drug, Dr. Olson said. Rigid prescription guidelines by insurers make it difficult to treat patients with complicated illnesses. The complexity of treating behavioral illnesses sometimes requires physicians to try several medications and dosages before finding the correct mix, he said.

A spokesman for Buckeye Community Health Plan, which covers more than 130,000 Medicaid recipients in Ohio through a contract with the state, said the firm wouldn't comment about individual cases. He directed The Blade to the Ohio Association of Health Plans for comment, but an association spokesman said she couldn't address Dr. Olson's concerns.

Last year, Dr. Olson said Buckeye covered a few of his patients on dosages of a medication higher than those recommended by the Food and Drug Administration, which he said isn't unusual for insurers to do. The drugs worked.

'They were stable,' Dr. Olson said. 'School had turned around. Family had turned around. Self-esteem had gone up. Things were going great.'

But six months after one patient was on the higher doseage, Buckeye determined that it would no longer cover the prescription at that level.

The patient struggled for up to six months while trying alternative medications as Dr. Olson fought the insurance company to approve the dosage of his original prescription. Dr. Olson ended up switching to a different treatment plan, which wasn't as effective for the patient but was covered by Buckeye.

'But for four to six months, there was a lot of trouble,' Dr. Olson said.

One of his patients, Sarah, was almost arrested for fighting with other children after she stopped taking the drugs Dr. Olson prescribed.

'Stability is our thing,' said Mrs. Dunbar, Sarah's mother. 'When she doesn't get her medication, she's not too happy.'

Obstacles to testing

The limitations insurers place on doctors' ability to treat their patients extend well beyond the prescriptions they write.

Dr. Rebecca Koehl said she was dumbfounded when an insurer initially denied her order for a stress test for a patient suffering with chest pains and other risk factors.

'They said a chest pain wasn't an adequate diagnosis to get a stress test,' recalled Dr. Koehl, a family practice physician in Cincinnati for nearly five years. 'If chest pain wasn't a diagnosis to get a stress test, I don't know what is. It is ridiculous.'

To get the approval for her patient, Dr. Koehl resorted to tough talk with the insurance representative.

'It finally got to the point where I said, You know what, let me have your name, and I will give your name to this patient's wife, and when [the patient] has died from a heart attack, I'll be sure she knows who to call to sue because you are denying him medical care.''

Preventive measures

Sometimes the limitations arise from the agreements insurers reach with employers who pay health-care premiums.

Dr. Rick Wiecek, a surgeon in Fremont, recently had a 50-year-old patient pay for his own colonoscopy after his insurer, Medical Mutual, refused to cover the test even though the patient was at a recommended age for the screening. The test discovered a large benign tumor that could have progressed to cancer, Dr. Wiecek said.

Medical Mutual recommends employers pay for plans that include screening colonoscopies starting at age 50, which can help prevent cancer, but not all insurance plans do, said Dr. Rzewnicki, the insurer's chief medical officer.

Some preventive tests, including mammograms and Pap smears, must be covered by law, but colonoscopies are among those that do not have to be, he said.

'That's where we really get in trouble,' Dr. Rzewnicki said. 'We feel strongly about coverage for this. We try to put it to the employer that it is cost-effective.'

Most patients won't pay $1,000 or more out of pocket for their own colon screening, said Dr. Saunders, the Warren, Ohio, general surgeon.

Dr. Saunders is anticipating a time when he'll recommend a colonoscopy for a patient, but the patient will forgo the test when insurance won't cover it and he can't afford it.

'Later on he'll come back with a colon tumor, and someone will say to me, Why didn't you do a colonoscopy?' and I'll say, I tried to but he didn't want to do it, couldn't afford it, and the insurance company said no,'' Dr. Saunders said.

'That's why I try to fight for everything I can fight for. I want my patients to get the proper care, no matter the costs,' he said. 'You would think that doing preventive care and doing the colonoscopy would prevent the huge bill later on if you find something now. That's not the way the insurance companies think, unfortunately.'

Dr. Joe Assenmacher of Toledo says he s become frustrated by doing battle with insurance companies. On a daily basis I have to change what I do because of insurance companies telling me what I can and cannot do, he says. It s all about money. That s what it is.

Access to care

Doctors say they've become mired in paperwork and frustrated by endless phone calls, which come as a result of trying to order medication, testing, referrals, or procedures for patients.

Time spent battling insurers, physicians say, takes away from time with patients, increases waits, and makes it more likely that they will make mistakes.

To combat rising costs and hassles, some doctors have stopped seeing Medicare and Medicaid patients or treating people covered by certain insurers. Other physicians have sworn off accepting insurance plans, instead opting to run cash-only practices. Some say their private practices are teetering on the edge of bankruptcy and being kept afloat only by personal loans.

Ultimately, with many doctors refusing to accept certain health plans and with increased demands on doctors' time and staff, there's a fear among physicians that a shortage of access to care is in the offing.

Financial struggles

Dr. Joe Assenmacher, a Toledo surgeon, and his father, Dr. Dennis Assenmacher, sold their practice to ProMedica Physician Group two years ago. The father-son orthopedic team was struggling financially because of insurance changes, the younger Dr. Assenmacher said, and now ProMedica handles billing and other issues.

While Dr. Joe Assenmacher still enjoys being a physician, he's become frustrated by doing battle with insurance companies.

'On a daily basis I have to change what I do because of insurance companies telling me what I can and cannot do,' he said. 'It's all about money. That's what it is.'

Medical Mutual, for example, limits payments for visco supplements, injections that can lubricate knees, provide arthritis pain relief, and stave off joint replacements. Some patients have had premature knee replacements without trying the treatment, Dr. Joe Assenmacher said.

Visco treatments are covered by Medical Mutual if established criteria are met, and that information is available to doctors online, said Dr. Rzewnicki, the insurer's chief medical officer. Medical Mutual follows recommendations from two medical associations, one for rheumatolgists and the other for orthopedists, to establish those guidelines, he said.

Meanwhile, Dr. Assenmacher said, Medicare reimbursements are so low the practice would barely break even. Insurers then follow Medicare's lead, paying doctors based on its rates, or less, he said.

At the same time, under federal law, it is illegal for doctors to collectively bargain or share their rates with other physicians, Dr. Assenmacher said. All of these factors make it difficult for doctors' offices to prosper.

'I've got a mortgage payment, too. I have kids who have to go to college,' Dr. Assenmacher said.

Overall compensation for specialists nationwide remained flat last year considering inflation, while primary care doctors made more money after years of flat or declining revenue, according to the Medical Group Management Association, an organization of managers of doctors' offices and groups across the country.

Specialists on average nationwide received $332,450 in compensation last year, up from $322,259 in 2006 and $296,464 in 2003, according to the association. Primary-care doctors nationwide received $182,322 last year, up from $171,519 in 2006 and $156,902 in 2003, it said.

It is a calling'

Although their salaries remain far above the average household income, physicians say medical school loans, expensive malpractice insurance, and the frustrations of trying to heal their patients while contending with interference from insurers take their toll.

Some have chosen other career paths, seeking their master's of business administration degrees while others have retired early. Many, though, say they will continue to practice medicine because they feel it is their calling.

'Most of the major insurers and the policymakers on Capitol Hill, they all understand that those of us that went into medicine because it is a calling and they have no compunction whatsoever about using my professionalism and my ethics against [me],' said Dr. Alan Birnbaum, a rheumatologist in South Bend, Ind. 'They'll cut our reimbursement; they'll do so unilaterally. We have no recourse, and what we will do is yell and scream and set our hair on fire and pick up the chart and go see the patient anyway. I'll scrub up and go back to the operating room anyway.'

Contact Steve Eder at: seder@theblade.com or 419-304-1680.