The good fight: Drugs for cancer treatment making progress

1/2/2011

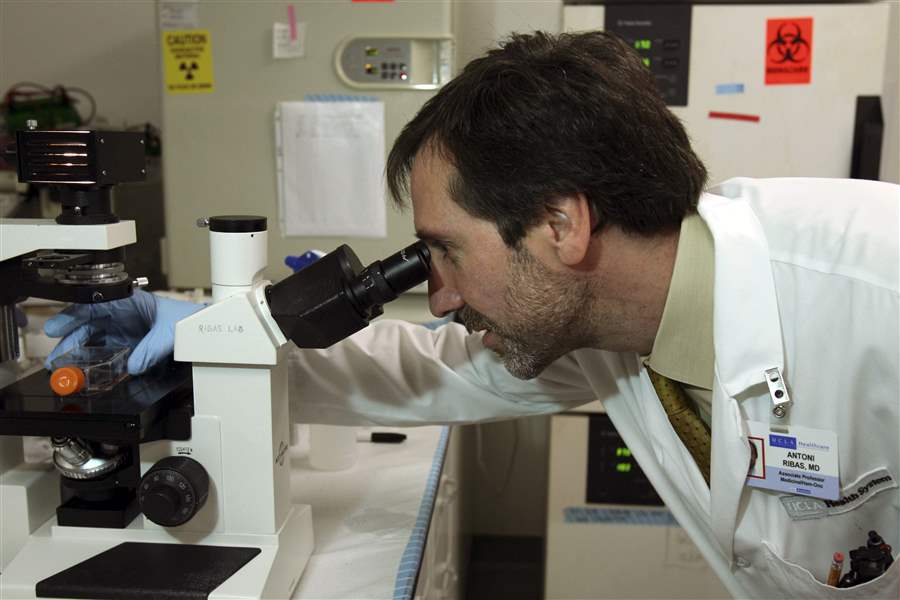

Dr. Antoni Ribas views cancer cells through a microscope.

ANN JOHANSSON / NYT

LOS ANGELES — They had told him on his last visit: The experimental drug that had so miraculously melted his tumors was no longer working. His legs were swollen, the melanoma erupting in angry black lumps. The patient, a computer consultant in his 40s, had little time left.

And now the man's doctor, Roger Lo of the cancer center at the University of California, Los Angeles, was calling to ask whether they could harvest a slice of one of his resurgent tumors for research he would almost certainly not be alive to benefit from. He would need to fly to Los Angeles from Northern California at his own expense, subject himself to an injection of anesthetic and the slight risk of infection, and spend yet another afternoon in the hospital.

“I was hoping,” Dr. Lo said that day last spring, “you would come in for a biopsy.”

The hope lies in a new breed of cancer drugs that work by blocking the particular genetic defect driving an individual tumor's out-of-control growth — in the case of Lo's patient, a single overactive protein. If researchers can pinpoint which new genetic alteration is driving the cancer when it evades the blockade — as it nearly always does — similarly tailored drugs may be able to hold it off for longer. The crucial evidence resides in the tumor cells of patients who, like Dr. Lo's, have relapsed.

Skin cells removed from the patient are placed in a vial.

But the need to ask those who know their time is short to undergo another invasive procedure in the name of science is just one obstacle to what many oncologists see as the best chance to give future cancer patients a more permanent reprieve.

A regulatory process that can take years to approve a drug for sale means that, instead of thousands of patients to draw on, only the few hundred who receive the drug through clinical trials are available for such research. Ethical review boards frown on any procedure that exposes patients to unnecessary risk, like the rupturing of a blood vessel or puncturing of a lung. Some hard-won tumor samples prove unsuitable for research.

Then there is the question of who will pay for the biopsies, which cost as much as $5,000 and typically cannot be billed to insurance. Dr. Lo, for one, covered the costs when there was no other means to pay.

As drugs tailored to the genetics of particular tumors make their way through early clinical trials, similar quests to improve on them are being undertaken by researchers in the various forms of a disease that kills more than a half-million Americans and millions more people worldwide every year.

Dr. Lo's quest to understand how melanoma forges its resistance to the drug PLX4032, made by Roche, illustrates the Herculean effort required to take even a baby step toward a cure for cancer. Finding a single clue that could lead to the testing of one new drug that might help a small fraction of patients took two long years.

But it also shows how such progress emerges, from a complex mix of academic ambition, collaboration, and competition among scientists, and, especially, the willing participation of dying patients.

Dr. Antoni Ribas views cancer cells through a microscope.

When the man Dr. Lo had called arrived in his office a week later, tumors covered his legs from the bottom of his feet to his groin. Some of them were infected, their odor so overwhelming that the doctor put on a mask before administering an anesthetic and cutting into his left thigh.

A researcher's trials

Roger Lo, 38, was an unlikely player in the scramble to improve on the Roche drug, which had been given to only a handful of patients when its successes began to grab the field's attention in late 2008.

An assistant professor in dermatology, he had started his own laboratory only a few months earlier and had been advised by senior colleagues to avoid high-risk projects until he secured a steady source of financial support.

But like others in the field, he was galvanized by watching melanoma patients respond to the Roche drug, the first ever to reliably slow a disease that typically kills within a year of diagnosis — and rarely responds to chemotherapy.

Studying how to prevent a relapse, he argued in a grant proposal in early 2009, was “of paramount importance.”

Impressed by his drive, and equally eager to realize the full promise of the drug's approach, Dr. Antoni Ribas, the melanoma oncologist running UCLA's arm of the drug's clinical trial, agreed to collaborate with Dr. Lo.

Bigger, better-financed laboratories pursuing the same question might reach an answer first, Dr. Ribas warned.

But Dr. Lo had reason to hope the results would be published in a leading journal, if he was the first to find the culprit responsible for reigniting the cancer, among the many possibilities. That could prompt drug companies to speed the development of a new therapy.

Lacking tumor samples from patients in the Roche trial, Dr. Lo instead sought to replicate the cancer's resistance to the drug by feeding a steady diet of the drug to melanoma cells taken from three previous patients who had never received it. When the few cancer cells that survived the onslaught began to grow in their petri dishes, he used those, now resistant to the drug, to begin his search.

It could have been straightforward. Many researchers believed the answer would be that the gene whose mutation initially made the protein that drove the cancer's uncontrolled growth had mutated again, as had happened in other cancers. In a few cases, a new drug tailored to the new mutations had lengthened remissions.

But Dr. Lo found no evidence of this. Nor did he find the smoking gun in several other genes linked to the growth of other cancers.

Instead, he began the painstaking process of measuring the activity of hundreds of proteins that might have driven the cancer's uncontrolled growth. The experiments required modifying the levels of each protein in the drug-resistant cells, dosing them with the drug and checking every few hours to see how fast they were growing. With only two junior scientists and a technician in his laboratory, Dr. Lo performed much of the work himself.

Even so, he knew, nothing he found in the cells whose resistance he had artificially bred in the lab would matter unless he also found it in the patients who had relapsed.

Those who wonder whether a single patient can help cancer research should know the case of Lee Reyes.

Thirty years old when his advanced melanoma was diagnosed in early 2008, Mr. Reyes was distraught at how little he had accomplished. Introverted and a perfectionist, he had dropped out of college and lived with his parents in Fresno, Calif. He cycled through video game systems, favoring the Xbox. He loved flying and thought about getting a helicopter pilot's license, but never pursued it.

“For the better part of about 10 years I did close to nothing,” he said two years ago. “I just always felt I had so much time.”

One of Dr. Ribas' first patients in the trial of the Roche drug, Mr. Reyes was selected because he was among the half of melanoma patients whose tumors carried the overactive protein the drug blocked. As it would for nearly every patient in the trial, the drug held his cancer at bay for several months. But as would happen with the others, his response did not last.

With his life at immediate risk because of a melanoma tumor that had metastasized to his heart, Mr. Reyes traveled to UCLA for surgery in May, 2009, agreeing to let his tumor be used for research.

On Dr. Ribas' instructions, a technician stood in Mr. Reyes' surgery room and, as soon as the surgeon extracted the tumor, ran with it to the nearby laboratory to reduce the chance of exposure to contamination. To coax the cancer cells to thrive so that Dr. Lo could run them through a battery of tests, it was sliced up with sterile knives and deposited, in a flask with sugar solution, in an incubator.

“Let's hope it grows,” Dr. Ribas said to Dr. Lo.

On a visit to Mr. Reyes' room after the surgery, Dr. Ribas did not discuss the future with his patient. They both knew the options were limited. Instead, they talked of animals: Mr. Reyes' affinity for monkeys — he was clutching a stuffed one from a hospital gift shop — and Dr. Ribas' for sea otters.

When Mr. Reyes died a few months later, Dr. Ribas called his mother to offer his condolences, as is his custom. And then he told her something else.

“He said Lee is helping them,” Ellen Reyes told her husband.

Mr. Reyes' cells were growing.

It would take months for Mr. Reyes' cells to multiply to the numbers Dr. Lo needed to perform his tests. And that summer, the foundation he had hoped would finance his research judged his grant proposal “too ambitious” for a junior investigator.

But by late September, 2009, using the laboratory cells he had earlier bred to resist the Roche drug, he had narrowed his search.

The cancer's new driver, he believed, was one of 42 proteins on the surface of the cell. A few weeks later, he closed in. An experiment that could detect all 42 found a single culprit, appearing as twin dots of black on the translucent background of the film: The resistant cells contained 10 times more of the protein than those that were still responding to the Roche drug in Dr. Lo's petri dishes.

And, he noted with excitement, a drug designed to block that protein was already being prescribed for other cancers. Perhaps a solution for patients was available already.

But as he prepared to see whether Mr. Reyes' cells bore out the observation, Dr. Lo tried to restrain his hopes.

“We have a likely candidate,” he told Dr. Ribas carefully.

It was probable, he reminded himself, that this protein was not the source of the cancer's resistance in all patients. In fact, the cancer could reroute itself differently in every patient. Even if the theory was right, Mr. Reyes' tumor might not reflect it.

In October, as the precious cells grew close to the number required for the experiment, Dr. Ribas received a box in the mail. In it was a stuffed sea otter, and a note from Mr. Reyes' mother.

They had visited the Monterey Aquarium over the summer, she wrote. Mr. Reyes had bought the otter to take to Dr. Ribas on his next

trip.

On a Saturday night in mid-November, Dr. Lo called Dr. Ribas. He was looking at the film showing the results of the experiment on Mr. Reyes' cells. On the translucent background, the same twin dots showed black.

The patient's cells, still living, harbored levels of the protein far higher than even Dr. Lo's laboratory models.

“Toni,” he said. “You have to see this for yourself.”

To be confident that his find was not a fluke, Dr. Lo needed more samples from other patients. Their goal would be 10, he and Dr. Ribas agreed in late-night e-mail exchanges. The best would be “before” and “after” snapshots from patients at the beginning of their treatment and after they had relapsed. But those were in short supply.

Only 48 patients had been treated in the drug's first trial, eight at each of six leading cancer centers. Many had not been biopsied when their cancer returned. Some of the biopsies had been sent to Roche, which had not yet shared its own research with the academic researchers.

Briefly, researchers at the six sites contemplated pooling the few samples in their possession, and sharing authorship of their results. But the tissues could be subjected to only so many tests before being used up. And success in academia can hinge on being listed as a paper's lead author. When several group discussions failed to yield even a complete accounting of who had how many, researchers agreed to stay in touch, but go it separately.

Still, in late 2009, Ribas approached two of the oncologists he knew to ask if they would share samples with Dr. Lo.

‘'I think he really has something,” he told the two, Dr. Jeffrey Sosman and Dr. Grant McArthur.

Four tumor samples, two from each doctor, arrived a few days later, by Federal Express. One, from a retiredmath teacher in Tennessee, tested positive for high levels of Dr. Lo's protein.

The same protein was hyperactive in another sample, which came from a Croatian patient of Dr. Ribas' who had been commuting to Los Angeles for treatment. The patient had surgery in Croatia to remove a tumor in his abdomen and requested that it be sent to the doctor.

Like everyone treating the patients in the Roche trial, Drs. Lo and Ribas were growing increasingly tormented by the knowledge that they could not promise more than a few months' reprieve to the patients enrolled in the drug trial.

They knew, too, that other researchers were close to publishing their own findings. One had given a presentation at a conference, and there was a rumor that his paper had been tentatively accepted by Nature, a premier science journal.

Over the first six months of this year, the doctors renewed their efforts to collect biopsies. Dr. Lo sent gentle e-mail reminders to the other oncologists with patients on the Roche drug, who might forget to ask, or sidestep the difficult conversation.

He juggled his schedule to be available whenever the opportunity arose, borrowing exam rooms to squeeze patients in. He scraped exposed tumor off the neck of a dance teacher in her 60s, and sliced into the lower back of a mortgage broker in her 50s.

Roche's rules for how biopsies would be stored in the next, larger trial of its drug made it impossible to perform many of the tests Dr. Lo wanted to try. So the UCLA doctors asked patients to sign a separate consent form, authorized by the university's ethical review board, for research that would be conducted independent of the drug company.

There were some biopsies they did not get. One patient's family volunteered an autopsy if it would help, but the timing made it impossible: Dr. Lo needed living tissue for the studies he was conducting. The doctors decided against asking another patient, a young mother, whose tumor was in the liver. The risk of complications did not justify the benefit.

A prominent immunologist from San Diego was willing to subject himself to a biopsy of a tumor near his knee, but the UCLA surgeon turned him away on the operating table, judging it too painful to remove. Still, when the immunologist, Dr. Norman Klinman, underwent surgery in San Diego after relapsing, his son raced to deliver his tumor sample, strapped into the front seat of his car in a container of dry ice, to Dr. Ribas' laboratory.

By early May, they had nine samples.

Dr. Lo's three lab workers had worked nearly every weekend for a year, and he lacked the money to hire more. Another of his grant proposals had been turned down because the Roche drug, a reviewer said, was too early in its testing to warrant a search for the cause of resistance to it.

When the machine they used to measure cell growth broke down that month and dozens of experiments had to be redone, Dr. Lo's postdoctoral trainee, Ramin Nazarian, mentioned a long-postponed trip to see relatives on the East Coast.

“Put it on hold,” Dr. Lo said. “We're almost there.”

When Dr. Lo submitted his paper to Nature in July, he had collected tumor samples from 12 patients. Of the four that contained his suspect protein, three of the patients had died by the time he had identified it in their biopsy.

But the last one came from a 54-year-old Canadian named Wes Coyle, who was alive, but barely, when Dr. Lo confirmed the protein's presence through a biopsy of a tumor in his pelvis. It was the first time that, using his and Dr. Lo's research, Dr. Ribas could try to help a patient who had relapsed. He warned Mr. Coyle's sister Peggy Coyle Seaver, who was caring for her brother, that it was a long shot. But he prescribed the drug, made by Pfizer, that was known to block the protein in some other cancers.

For two weeks, Ms. Seaver reported to the doctor, her brother was suddenly able to eat again. Yet he died soon after that.

Another opportunity arose with a fifth patient who contributed tumor samples to Dr. Lo's collection, an avid gardener in Los Angeles. Her sample carried a gene mutation that suggested a second possible escape route for the cancer. But on a clinical trial for an drug specifically designed to block it, she quickly deteriorated.

Most likely, the two doctors knew, single drugs would not alone block the resurgent cancer, even if they were hitting the right targets.

“Damn it!” Dr. Ribas said, calling Dr. Lo when he saw the tumors growing on her scans. Of the 12 patient samples, Dr. Lo had identified the likely source of the cancer's resurgence in five. In August, with a grant he received from the Melanoma Research Alliance, along with researchers at other institutions, Dr. Lo began to probe the rest.

And in late November, after requesting another round of experiments, Nature published his paper, along with one from a competing researcher.

Ms. Seaver scanned the copy Dr. Ribas sent her, her breath catching when she recognized her brother, listed in a table as the 54-year-old male who had a 78-day response. “It feels like Wesley is still alive,” she told her husband.

Brian Lewis, a paramedic whose wife Dr. Lo had decided against asking for a liver biopsy, read about his paper on the Internet, and contacted the doctor to ask whether providing one now would help him. His wife was doing poorly, but they had two young children, he wrote, “and I would hate to see them fight the same battle their mom is fighting.”

A researcher at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, consulted his own batch of five tumor samples from patients who had relapsed. One of them, he told colleagues on a conference call, had the second mutation Dr. Lo had found.

In early December, Dr. Ribas visited Roche's offices in San Francisco. The data in the paper, he argued, made a case for clinical trials of combinations of drugs the company was already developing. Researchers would need to take biopsies from patients in those trials, too, they all agreed.

Because the cancer, even if blocked a second time, might find another way through.

‘'We have a lot more to do,” Dr. Lo tells his laboratory staff every day.