Spike in heroin-related deaths in area reflects access, potency

Toledo family's loss more than a statistic

3/21/2013

Matthew Schroeder of Toledo, 25, died in September, 2012, from a combined drug toxicity.

John Schroeder, left, Shawn Schroeder, Sandra Schroeder, Christopher Schroeder, and his partner, Adrian Lilly, pose in front of a painted portrait of Matthew Schroeder, who died of a heroin overdose at his bedroom desk in the Old West End. John and Sandra are Matthew's parents, and Shawn and Christopher are brothers.

Matthew Schroeder was a son and brother, a 25-year-old avid reader and music lover.

He was also a drug addict.

He died at his bedroom desk in the Old West End home of his parents, John and Sandra Schroeder.

On Sept. 22, his mother made a pot of chili and waited for its simmering aroma to rouse her son from his room. She hadn’t seen him all day — not unusual given his night-owl tendencies — but when he didn’t appear for dinner she climbed the stairs, turned the doorknob, and screamed.

The coroner determined the cause of death: Combined drug toxicity, with heroin and other drugs found in his system.

Suddenly, Matthew Schroeder was a statistic, one in an increasing number of local, heroin-related deaths. His family, however, refuses to define him as a number or a notch in a trend.

“Matt didn’t just wake up in the morning and say, ‘Hey, I’m going to try heroin,’” Ms. Schroeder said. “He wanted to be a person that made a difference in life; he just didn’t want to pass through life.”

Heroin-related overdose deaths have spiked in recent years. In 2010, 14 such deaths occurred in the region, increasing to 31 in 2011, and to 55 last year. As of early February, 14 heroin-related deaths had been tracked this year by the Lucas County coroner’s office.

Lucas County accounts for an estimated 60 percent of those cases. The remainder come from throughout the region, which includes more than 20 counties — most in northwest Ohio — served by the Lucas County coroner’s toxicology lab.

“We’re having lots of drug overdoses,” Chief Toxicologist Dr. Robert Forney said.

Like others, he links the heroin problem to the prevalence of prescription painkillers, drugs some become dependent on before transitioning to heroin.

“Heroin is an opioid, so the natural progression here is that people become addicted to prescription opioids first, and then when they can no longer afford or no longer obtain prescription opioids, they move on to heroin,” said Orman Hall, director of the Ohio Department of Alcohol and Drug Addiction Services.

Mr. Schroeder loved his family, and they loved him back no matter his struggles.

His history with drugs was more complex.

In 2000, his parents sued the Maumee Board of Education and school officials on behalf of their son, saying he was the victim of physical and verbal attacks by his peers stemming from his support of gay-rights issues.

His older brother, Christopher, is gay.

The suit was settled out of court.

When discussing Mr. Schroeder’s substance abuse, family members circle back to those life-altering events.

Ms. Schroeder said her son was traumatized by the assaults, was prescribed psychotropic and antidepressant drugs with bad side effects, and received various diagnoses, including post-traumatic stress and obsessive-compulsive disorders. After dental procedures as a teenager, he also was prescribed painkillers.

His family believes the substance abuse later snowballed from those drugs and the inclination of medical and mental health professionals to treat problems by prescribing pills. The turn to heroin, and the escape it offered, was more recent and possibly sparked by its availability, Christopher Schroeder said.

“If you are looking at a national epidemic of prescription-drug abuse and other drug abuse — this is systemic,” he said. “Drug addict is such a powerful label that people can’t look past. They forget the humanity of that person that’s struggling with addiction.”

Drug abuse led to numerous legal problems for Matthew Schroeder.

He served a 180-day jail sentence for a first-degree misdemeanor assault in Ottawa County that stemmed from an incident involving his girlfriend. He died the month after his August release.

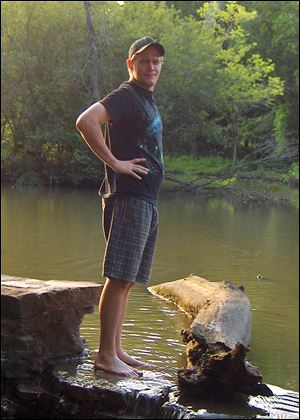

Matthew Schroeder of Toledo, 25, died in September, 2012, from a combined drug toxicity.

Heroin trends

For some, heroin no longer carries the same stigma once associated with the street drug, said Bob Stokes, president and chief executive officer for Toledo-based COMPASS Corp. for Recovery Services.

An older generation might think of heroin as a drug “so scary” it was “restricted to hardcore addicts,” but now, "heroin, because of its availability — it is quick and easy to get and utilize — offers them a very quick high,” Mr. Stokes said.

He noticed a trend toward younger substance abusers at methadone clinics, a treatment for those with heroin or prescription-drug problems. Those addicts are more likely now than years past to be white, female, and younger, he and Mr. Hall said.

Billing data from the Mental Health and Recovery Services Board of Lucas County shows a median age of 32 for services that include prescription-drug and heroin help, and executive director Scott Sylak does not think that number has changed significantly.

A review of 18 heroin-related regional deaths from fall, 2012, found three females and 15 males, one black person and 17 white people, and an average age of about 42. Five also had consumed alcohol, and most had other drugs in their systems.

Toledo police Sgt. Joe Heffernan connects overdose deaths to an influx of “China white,” a type of heroin more potent than the brown kind traditionally more prevalent here.

Toledo police seized about 1,454 grams of heroin in 2011, but only 5.3 grams were the white type. Last year brought a big shift: of the 3,371 total grams seized, about 68 percent was white. So far this year, white heroin accounts for about 80 percent of the heroin seized.

Among reasons for white heroin’s local surge is user demand and origin, Sergeant Heffernan said.

Historically trafficked through Asia, he said, a lot of white heroin is now refined in Mexico, which opens up access to sophisticated drug-trafficking networks.

Users may not realize China white’s potency, leading to overdose death “before they even know it,” he said.

A family photo shows Matthew Schroeder at Side Cut Metropark. ‘Matt didn’t just wake up in the morning and say, “Hey, I’m going to try heroin,”’ his mother, Sandra Schroeder, said.

Crossing boundaries

Lucas County Sheriff John Tharp reported more heroin activity in the last several years, including among young adults. He said heroin use is not confined to one particular part of the county.

“It’s crossing all ... economic and social boundaries,” he said.

The Hancock County Coroner’s Office reported nine heroin-related deaths since 2010, while Ottawa County reported two deaths in 2009, one in 2010, and none since.

Heroin-related deaths are not just a local concern. In 2006, unintentional poisoning surpassed traffic crashes as Ohio’s leading cause of injury-related deaths, according to the Ohio Department of Health.

In 2010, the most recent year for which statistics are available, 1,639 state residents died from unintentional poisonings. That year, 45 percent of the state’s unintended poisoning fatalities involved prescription opioids.

The state health department also has reported that heroin-overdose deaths jumped from an average of 100 per year statewide between 2000 and 2005 to about 224 per year between 2006 and 2010, the latter accounting for 15 percent of all overdose deaths.

After his jail release, Mr. Schroeder wanted to commit to sobriety, his family said.

He sought help for substance abuse and physical ailments at various facilities and received some inpatient treatments. His family said other treatment attempts were thwarted because of various program policies, no immediately available recovery bed at one center, and health-insurance confusion.

“Matt’s trying so hard to stay clean and to get help, and we’re trying to help him succeed in that. But everywhere we turn, it’s like a door was slammed in our face,” said Adrian Lilly, Christopher Schroeder's longtime partner and Matthew’s good friend.

Solving the drug problem requires a systemwide overhaul, his family believes.

Among their concerns: Jails should focus attention on substance abuse and mental illness, and care should be better coordinated among caseworkers, hospitals, and other agencies.

Those just released from jail need help finding resources in the outside world. More recovery program funding is needed so substance abusers can check into facilities without going on waiting lists.

Mr. Hall, director of the state’s alcohol and drug-addiction services department, wants to make sure people understand prescription-drug dangers and how those pills can be addictive and lead to heroin use.

He called on health-care providers to look for other ways to treat chronic pain besides prescribing painkillers, and said those struggling with addiction need access to treatment medications along with counseling.

Substance-abuse recovery is possible, and there are community resources ready to help, officials said. Lucas County’s mental health and recovery services agency funds medication-assisted treatment for drug dependence along with counseling, said Mr. Sylak. The agency is looking for ways to improve its effectiveness.

“We believe strongly in the power of treatment services. People with adequate treatment and support do get better,” he said.

Those who don’t know where to turn for substance abuse help can contact Central Access, where they can obtain referrals for treatment, at 419-255-3125.

Contact Vanessa McCray at: vmccray@theblade.com, or 419-724-6065.