CLINIC’S DEMISE BRINGS PAIN, JOY TO FACTIONS

Eyes turn to Toledo as flashpoint in abortion-rights controversy

6/22/2013

Carol Dunn in front of the Center for Choice in Toledo, which closed June 7.

THE BLADE/LORI KING

Buy This Image

Carol Dunn in front of the Center for Choice in Toledo, which closed June 7.

The answering machine at Center for Choice clicks on after several rings, quickly telling every caller of the clinic’s closure.

“Unfortunately we closed our doors as of Friday, June 7, due to restrictive abortion legislation in Ohio,” the message states.

Thirty years as a Toledo abortion provider over in about 30 seconds. To some, the words are an answer to prayer; to others, cause for alarm.

Capital Care Network, the only remaining local abortion clinic, could face the same fate, and its closure would make Toledo the biggest Ohio city without an abortion provider.

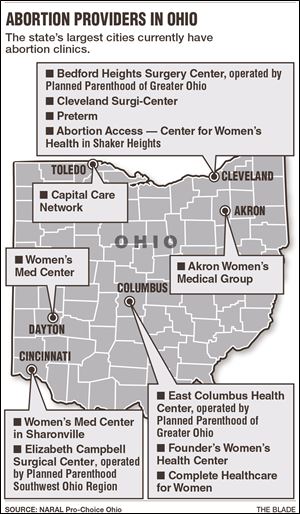

Abortion providers in ohio

“We are a small piece to a community, and each piece that you don’t stand up for, it becomes a depletion of that whole community,” said Susan Postal, Center for Choice director.

Her operation ended after local hospitals declined to enter into a transfer agreement with the clinic. State code requires a pact for the transfer of patients needing emergency treatment.

The University of Toledo Medical Center stopped negotiating an agreement with the clinic and alerted Capital Care Network it would not renew an agreement that expires on July 31.

University of Toledo President Lloyd Jacobs has said he wanted to keep the former Medical College of Ohio Hospital neutral on the abortion debate.

A spokesman for ProMedica, which at one point had an agreement with Center for Choice, issued a statement saying the hospital doesn’t “want to be put into a position of choosing a political position that is only divisive and polarizing.” Both UTMC and ProMedica officials said the hospitals will continue to treat those in need of emergency care.

Lack of a transfer agreement is a violation that could lead to the revocation of Capital Care Network’s license, according to the Ohio Department of Health. The network’s director did not return calls or an email requesting comment.

The undoing of one and possibly both of Toledo’s abortion providers thrusts the city into the state spotlight in a year when abortion foes are mourning the 40th anniversary of Roe vs. Wade. Abortion-rights advocates have worried about the tightening restrictions since the monumental U.S. Supreme Court decision legalized abortion.

All the while, the state’s abortion numbers continue a fairly steady fall, a testament to contraceptive use and sex education, according to Kellie Copeland, executive director of NARAL Pro-Choice Ohio.

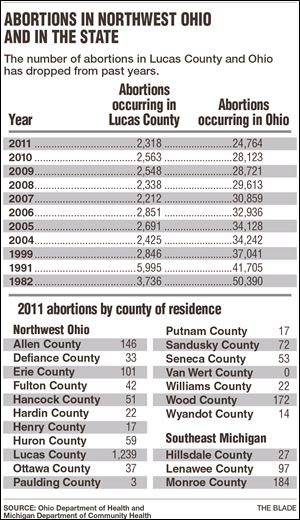

Ohio Right to Life President Mike Gonidakis credits the decline partly to birth control but contends more pregnant women want to have a baby or choose adoption. In Ohio, the health department reported abortions dropped from 50,390 in 1982 to 24,764 in 2011.

“We’ve dropped over 50 percent. Our goal is to end abortion,” Mr. Gonidakis said.

Local history

Toledo Medical Services, the area’s first abortion clinic, opened in March, 1974, and Carol Dunn, who worked at the clinic, became a face of the local abortion-rights movement.

In 1983, she opened her own clinic, Center for Choice, on Michigan Street.

A newspaper clipping from the mid-1970s shows Ms. Dunn at Toledo Medical Services, a rotary-dial telephone tucked in the corner of a desk. In a photo from 1986, she sits in a makeshift office after a protester’s fire bomb destroyed portions of the Center for Choice.

The damage from the bomb led to the clinic’s eviction from its Michigan Street site and its relocation to a building on North Huron Street. After the surrounding area was selected as the site of the downtown baseball stadium, Ms. Dunn purchased the now-shuttered 22nd Street building. Ms. Postal, Center for Choice’s owner and director, later took over operations.

Over the years, Ms. Dunn said the clinic faced opposition and protests — from the confrontational to the unusual.

In 1989, nearly 60 protesters were arrested after jumping from a truck and blocking the clinic’s doors for more than 10 hours. Two years later, a man jammed the clinic’s answering machine by repeatedly calling and reciting Bible verses.

Picketing still takes place, but Ms. Dunn said protests of the magnitude she once experienced don’t happen as often.

Ms. Copeland credits the decline in violence to the 1994 Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act, which made some offenses federal crimes.

Ms. Copeland said harassment from protesters is one reason why some clinics closed.

The number of abortion providers dropped nationally by 38 percent from the highest count of 2,908 in 1982 to 1,793 providers in 2008, the most recent year numbers were available from the Guttmacher Institute. Rachel Jones, senior research associate for the abortion-rights think tank, said reasons clinics close vary by state and year, and said increased regulation plays a role.

“I know we spent 40 years, or close to 40 years, explaining to patients why the threat [of closure] has always been there, and now it’s turned into reality,” Ms. Dunn said.

This month, she watched as the clinic she built closed.

The center’s phone rang sporadically on a recent morning, but the office lights were dimmed. Inside, Ms. Postal went about the tasks necessary to button up the business. She spoke with a mail carrier about where to deliver letters, and she prepared to tie up other loose ends.

She said the clinic’s demise is a community loss.

“Why are we not learning from historical stuff? Why are we going back to — potentially — that idea that no access is a good thing?” she said.

Abortions in NW Ohio and state

Other options

Ms. Postal is referring clients to the National Abortion Federation, which maintains a list of providers. She’s also spoken with Renee Chelian, administrator of Northland Family Planning Centers whose Michigan locations in Westland, Southfield, and Sterling Heights are among the closest to Toledo.

The Westland clinic, about 55 miles north of downtown Toledo and just off I-275, is poised to pick up more patients, especially if the second Toledo clinic shuts down. Ms. Chelian is updating her Web site with information for Ohio residents. She had been reluctant to market aggressively here because she hoped someone would challenge the Toledo closure.

“It doesn’t look like it’s going that way,” she said. “Women in Ohio are going to have to get in the car and drive halfway across the state. And right now, very soon, women in Toledo are going to have to drive an hour away.”

Center for Choice had clients who traveled from throughout northwest Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan. A dozen abortion providers remain clustered in Ohio’s major cities, including the lone clinic in Toledo, one in Dayton, two in the Cincinnati area, three in Columbus, one in Akron, and four in Cleveland, Ms. Copeland said. That doesn’t count hospitals that may perform abortions in cases of medical complications, she said.

Toledo’s pregnant women may have to arrange transportation, pay for gas, a hotel, child care, and time off work to make the trip, steps Ms. Chelian describe as “a burden.”

And while her clinics accept insurance, nationally only about 12 percent of abortions are paid for with private insurance, according to Guttmacher. Its study cited high deductibles or lack of coverage in plans.

Some choose to pay out-of-pocket for an abortion because they are concerned about confidentiality issues, Elizabeth Nash, a Guttmacher policy analyst, said.

Those who travel out-of-state for an abortion may not find a provider within their insurance network, meaning reimbursements could be less or more difficult to receive, Ms. Nash said.

Without local providers, Ms. Chelian and other abortion-rights supporters fear some desperate women will take dangerous measures to end a pregnancy on their own. It’s a concern Mr. Gonidakis of Ohio Right to Life dismissed as rhetoric and a “tired talking point,” saying abortion providers are still readily available.

Parishioners pray at Rosary Cathedral, celebrating the closing of the Center for Choice in Toledo. One abortion provider remains in the city.

Prayers answered

Ann Barrick stood on the sidewalk outside Center for Choice for the final time on June 6.

Nearly every week for nine years, Ms. Barrick joined protesters in prayer outside the abortion clinic.

They came in bitter cold and summer heat. They passed out rosaries and carried an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, regarded by some Catholics as protector of the unborn.

They hoped to reach pregnant women seeking an abortion — to offer support, to consider an alternative. Some women changed their minds. Ms. Barrick said she was present for the birth of a baby whose mother had contemplated abortion.

Sometimes she grew discouraged, especially the last few years.

“It just wears on you over and over and over to be there and know what’s going on in the building,” Ms. Barrick said. “People were surprised to hear me say that every single time I went down, my stomach would get in knots.”

A week after her last sidewalk shift, Ms. Barrick, the local coordinator of the anti-abortion rights campaign 40 Days for Life, joined nearly 100 others at Rosary Cathedral. The group Helpers of God’s Precious Infants holds a prayer vigil three times a year, in addition to meeting outside the clinic on Thursdays and Fridays.

The plan had been to follow the same routine as prior vigils. After Mass, those who wished would make the 1-mile trip to the clinic where they would pray the Rosary.

But this time, Mass featured a celebratory homily underneath the cathedral’s soaring, colorful ceiling. Afterward, those in attendance remained in wooden pews.

The clinic had closed.

“This evening we celebrate what God has done in raising up the dignity, in raising up the care that we have for women, by the closure of the Center for Choice. Indeed, there is one less option, but it was an option that attacked the dignity of a woman,” said the Rev. Mike Dandurand, pastor of St. Thomas More in Bowling Green.

Mary Kay Smith’s voice wavered as she spoke to those gathered.

“While we rejoice in this victory, let us remain prayerful that the Center for Choice remains closed and for the end to abortion in our country,” said Ms. Smith of Waterville, among those who regularly spoke with women outside the clinic.

What’s next?

Now that the epicenter of their efforts is no more, those who hoped so long for the clinic’s end aren’t sure what to do. Ms. Barrick said many of those who regularly met outside the clinic are still watching and waiting to see what happens next.

“We know that abortion still is there, and, you know, we’ve just got to keep praying for people to not feel the need for it,” she said.

Kathy Ferguson-McGinnis of Oregon helped establish Hope Home, an Oregon maternity home that supports pregnant women in crisis, and stood outside the clinic most Thursdays.

“We weren’t there just to save the baby; we were there to save both the mother and the baby,” she said. “We weren’t condemning her.”

The clinic’s closure is “joyous news,” but more work remains.

“This is a great step forward, but we’ve got a long way to go ... until Roe v. Wade is overturned,” she said. “We’re down here at the 11th hour, we need to get in the community so that this doesn’t get to be this point. We have to prevent the unwanted pregnancies.”

Ms. Smith isn’t sure what Helpers of God’s Precious Infants, the group that prayed and counseled outside the clinic, will do next.

“[Whatever] we feel called as a group to do, we’ll go from there,” she said. “Our fight’s not done.”

Mary Kay Smith, organizer of the Helpers of God's Precious Infants group, hugs a parishioner after the Mass at Rosary Cathedral in Toledo.

‘Test case’

Those on both sides of that political fight know the abortion debate rages on, a full four decades after Roe vs. Wade.

“One of the most hostile climates we’ve ever faced in Ohio,” is how Stephanie Kight, president and CEO of Planned Parenthood of Greater Ohio describes present-day policy maneuvering. A state budget provision would prohibit public hospitals from signing transfer agreements with abortion providers, and recently introduced legislation calls for women who want an abortion to wait longer, among other requirements.

At ground zero of the state’s swirling abortion discussion: Toledo.

“Everyone in the state knows what’s happening in Toledo,” Ms. Kight said. “You are already the test case in Toledo.”

Ms. Copeland of NARAL Pro-Choice Ohio also is watching the local situation as a “foreshadowing” of what could happen across the state.

“I think people really do feel under siege, attacked right now,” she said. “People just come to me and they say, ‘I can’t believe we are still having to fight for this.’”

But abortion-rights opponents said the passel of proposed policy changes reflect public sentiment.

Mr. Gonidakis of Ohio Right to Life said voters elected state officials, including the governor, who identify as “pro-life.” Young people, he said, are rejecting “this old notion of babies [as] burdens.”

“Toledo is a great area of the state. We are seeing more and more people choose life across the state of Ohio,” he said.

Ask Ms. Postal what all this means for Toledo, for abortion providers, for women, and she’ll shake her head and repeat, “I don’t know.” In her perfect world, people would realize quickly clinics here mustn’t close.

“It shouldn’t have happened in this city, but it did,” she said.

Contact Vanessa McCray at: vmccray@theblade.com or 419-724-6056, or on Twitter @vanmccray.