Fast forward: Altman: A lion in winter

4/15/2004

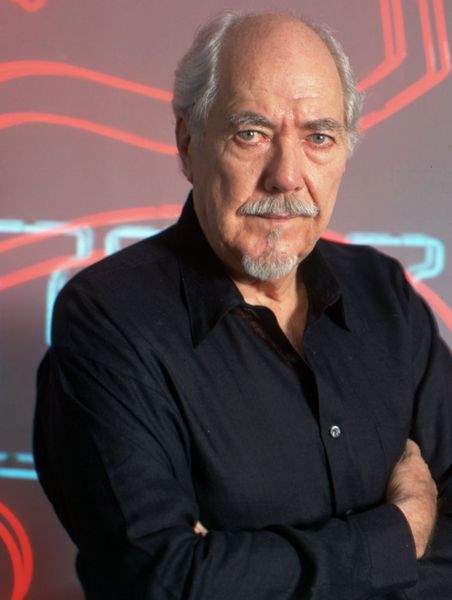

Altman

WYATT COUNTS / Associated Press

Any portrait of Robert Altman must begin with a gripe. This is only fair,

because any conversation with Robert Altman will eventually get around to his rocky relations with the rest of Hollywood, which regards him as a genius, occasionally rewards him with more

than hosannas, and yet, on most days, holds him at arm s length.

Only he doesn t actually gripe ... he just finds inroads you didn t know were there to deliver sardonic blasts of insight. For instance, a question about how he works with large ensembles gets an answer that veers through casting, camera placement, and method

acting, before arriving at this: Movie stars were invented at a certain time before my career started and they have caused me a lot of trouble over the years.

Then he goes into how Donald Sutherland and Elliott Gould maneuvered to have him thrown off M*A*S*H (without success,

of course); he spikes every anecdote with a little moral ballast ( You re going to lose most battles, but once you win a couple, a reputation is established. ), then finally brings his point full circle

and gets into the practical reasons for being weary of movie stars:

You can hardly get started when you cast movie stars because there s always some agent lurking around somewhere saying, Wait a minute. Charlie s trailer is supposed to be closest to the toilets.

And I say, Wait, he has a toilet in his trailer. They say, Not the point. He gets visitors. Those things get worked out. Then you learn Charlie doesn t work before 11.

He shrugs and smiles. The way Robert Altman looks and sounds at 79 is the way you expect Santa Claus to look and sound on Dec. 26. We talk on the outdoor patio of a restaurant in Toronto. His latest movie is the ballet drama The Company, and because, at the time of this interview last fall, the movie is still months from release, he doesn't yet know that Sony Pictures Classics will unceremoniously dump it.

But his expression is the expression of the irritated and unmotivated and worn. He looks exhausted, closed-off, his white hair and white beard frazzled and stiff.

He knows something is up with the film's release and he doesn't attempt to hide it:

"I have a limited audience. I'm never going to make a film that gets 14-year old boys into seats, and that's the largest audience. But I don't think about that, and if I had a blockbuster I wouldn't know how to handle it anyway."

He shrugs and smiles, again.

Shelly Duvall, left, and Sissy Spacek star in Altman's 1977 drama <i>3 Women</i>, which is being released on DVD this week.

And there's the rub: that's the way he's always looked and sounded, when M*A*S*H was a hit in 1970; when Gosford Park was a hit in 2001; when his great 1977 drama 3 Women, finally being released on DVD this week from Criterion ($39.95), was relegated to semiobscurity. Just like The Company. Minus the poundage he's put on in the last decade, this could be a portrait of Robert Altman at 59, when he was a washed-up maverick director without a commercial prospect to speak of. Or it could be a portrait of Robert Altman at 49, when he was a celebrated maverick, certain to have his stony face chiseled into any serious moviegoer's personal Mount Rushmore of American filmmakers.

The man has not changed.

"My artistic view is no different than the first time I made a film. You get facile in certain areas, but there's a danger of becoming too facile, of losing the art of what you're doing and just becoming skilled at the mechanics of filmmaking. And I don't think I've gotten better at the art of what I do. That's DNA. The rest is just learning to be efficient without stripping away the art."

Altman at 79 still names names. He still breathes red-hot ire at unions and studios alike. He still says things that show both a genuine respect and a casual disregard for actors and screenwriters.

He still considers making movies a "living kind of art" and values improvisation over using the script as a blueprint.

"People ask me what lines are mine and what lines are the screenwriter's. I don't even keep a script. On Gosford Park I had the great Julian Fellowes on the set, and I had like 30 top British actors, and when we would start to improvise, I could see his eyes just go into panic mode, and before the scene was even finished, we would have these new script pages with the improvisations included that made sure nobody would take his credit away from him."

As we talk, the phrase "for some reason they didn't fire me," or a slight variation of it, comes up three separate times.

None of which is surprising.

Altman - nearly 35 years after he made M*A*S*H; 30 years after he made Nashville and McCabe and Mrs. Miller, and a decade since rebounding (then sliding to the margins; then rebounding again) for the umpteenth time with The Player and Short Cuts - is a picture of a kind of perverse consistency.

He's consistent at being wildly inconsistent. And that's true also of our reaction to Altman: If he remains one of our most humane and surprising filmmakers, capable of keeping a respectful distance when he's in love with his subject, or going for the jugular when he's feeling self-righteous, he's also become our least understood director.

You could argue Robert Altman remains underrated, and he might agree. Once asked if he had better luck with European critics, Altman replied:

"Sure. But that's true of anybody. You have a tougher going in your own place and time. Jesus of Nazareth found that out."

Altman has been around so long you could program a decent film festival with just the movies he's made that have been overlooked. There are agreed-upon classics: The Player, The Long Goodbye, Gosford Park, Nashville, M*A*S*H, Short Cuts, McCabe and Mrs. Miller. The indefensible duds (which deserve their obscurity): Dr. T and the Women, Quintet, Ready-to-Wear, Fool for Love.

And then the wider, deeper pool of underrated Altman gems - a more divisive, often flawed, sometimes brilliant batch of movies, ideal for discovery on video. 3 Women, starring Sissy Spacek and Shelley Duvall as roommates who identify with each other a little too closely, is arguably the best Altman movie you've never seen: gauzy, funny, and restless. Its digressive comedy is completely in line with the Altman of Nashville and California Split, and deserving of a revival. But then so are Thieves Like Us, Vincent and Theo, Popeye, A Wedding, Cookie's Fortune, and Tanner '88, the campaign year HBO miniseries he created with Doonesbury cartoonist Gary Trudeau (currently being rerun on the Sundance Channel).

The Company (due on video in June) fits this last group perfectly: Altman follows the ups and downs of Chicago's Joffrey Ballet, but rather than latch on a melodrama of triumph and failure, he presents their routine as if it were inseparable from the seasons of the year. We find our own drama within his teeming troupe of artistic directors (including Malcolm McDowell) and dancers (led by Neve Campbell).

"Radio was great because the audience made up the pictures," Altman said.

"Then pictures took away their imaginations, just as music videos now take away from how they hear music. The audience doesn't have anything to do anymore, and that's always my biggest hurdle. So I try to disguise and hide what the image is about, muffle what is being said. If you don't allow the audience to participate a bit, the art is gone."

My favorite forgotten Altman is Secret Honor (1984), starring Toledo-native Philip Baker Hall as Richard Nixon, and with it Altman brought audience participation ever further: He shot in a dorm at the University of Michigan using a student crew.

"We performed it in Ann Arbor as a theater piece first," he said. "Then moved it to a set and we set up these monitors so the students outside the set could watch. It was a credited course, too. We used only two cameras, and I remember the [Michigan production] unions tried hard to shut us down. They said 'You're taking work away from our stage hands,' and we said, 'Well, your stage hands won't work for free and these students will.' Remember it's never easy for me to raise money, and when I do, it's for so little money that everyone has to do it because it's their labor of love."

He says this without emphasis. Altman at 79 doesn't want to become a sage. But asked how he's managed to make movies steadily through the constant commercial valleys of his career, he sits up and thinks for a second and then says:

"I started in television. I was doing this show called Whirlybirds in the 1950s. It was about these two guys who performed these .●.●. deeds or something. I had this scene where their helicopter is hijacked and they're walking through the woods. I was ahead of schedule and rooting around the prop truck and found a telephone booth. So I thought I would put it in the woods and these guys would be walking along and decide to call someone to come pick them up. But they don't have a dime, and just keep walking. Now I didn't know the editor on the series so I just sent the footage in.

"Later I'm sitting home one night and I remembered I had a Whirlybird on. I'm watching it and it's dreadful and then suddenly this scene with this telephone booth comes on, and it's so absurd. There was nobody covering first base. That's when I learned nobody is watching the store, and all I have to do is appear confident about what I'm doing, and that's what I do. But you have to still stand up for yourself. If you don't stand up for your artistic right to try something, it will be taken away. Believe me, suffer for it. You play their game, and you're really gonna suffer."

Christopher Borrelli can be reached at cborrelli@theblade.com

or 419-724-6117.