Movie review: Million Dollar Baby *****

1/28/2005

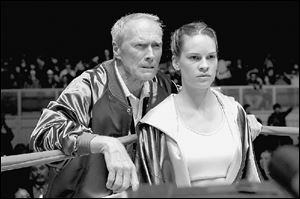

Frankie Dunn (Clint Eastwood) is a grizzled old trainer who agrees to coach a feisty upstart boxer,Maggie (Hilary Swank).

I should have guessed that Clint Eastwood s Million Dollar Baby which flew in from nowhere, like a haymaker to the head would be his masterpiece.

I should have guessed it when I heard that Warner Bros., the studio that eventually relented, didn t want to make the picture.

Eastwood has given a lot of disgusted reasons why: They said

boxing movies don t make money; they said the script was wrenching, too tough, too subtle for audiences to appreciate.

That irony is bound to become part of one of those great Hollywood almost-didn tget-made stories: Million Dollar Baby, far from inaccessible, is the kind of movie they don t make anymore: movies that are timeless in storytelling and tone, universal in aesthetics and emotions, straightforward in their plotting. It s the kind of studio picture that studios excelled at before television got in the way

and splintered the demographics a film that is as easily loved

by a parent as a teenager, as profound to a Republican as a Democrat, as entertaining to a grandfather as it is to Eminem.

Everyone, in other words.

Then there is the issue of Eastwood s story, which follows the moth-eaten formulas of dozens of boxing movies, lulling us with its amiability and familiarity, aligning itself with the cliches of the boxing movie universe: the grizzled old trainer (Eastwood) who doesn t coach girls, the feisty no-hope upstart waitress from the backwoods

(Hilary Swank), the wise old gym proprietor (Morgan Freeman)

who lends the picture not only a narrator but a moral backbone.

It s all been done endless times; it sounds routine, corny, old hat.

That is, until Million Dollar Baby veers down dark alleys, and

then down mature, less triumphant paths that the average studio picture wouldn t consider, much less shoot. You can see why

a Warner would balk. Eastwood risks losing some audience on a

third act that is unyielding in its force, but that deepens what

came before, and leaves you floored and pondering the meaning

of responsibility, faith, and what exactly makes up a family.

On the wall of Frankie Dunn s (Eastwood) gym is a sign that

reads: Winners are simply willing to do what losers won t. It s

more than an aphorism here. It s also the reason Eastwood, who

turns 75 in May, is doing the best movies of his life so late in his

career. And it s the reason that studios didn t want to make this.

Did I say last year that Mystic River was Eastwood s autumnal

masterpiece? Silly me. What I mean is this: Million Dollar Baby

is Eastwood s autumnal masterpiece, his instant classic about

how the bonds between people transcend family, and ugliness,

and even death. It s not a boxing picture, though the fights are

rousing and there s a definite pleasure, no doubt, in watching

the kind of sudden violence Swank throws down on her opponents

one after another.

It s more of a picture about a boxer, and her trainer, though it s

more about her trainer. If the role is a cliche, the details make him pop out: Dunn is a crusty, lapsed Catholic who reads Yeats in Gaelic, attends church every day, and follows the priest every

day, as well, just to engage him in a theological debate, we

assume. Dunn carries a cloud over him, starting with a daughter

he hasn t seen in 23 years, and a string of boxers he would

not go out on a limb for. There s not a lot of explanation, and

there shouldn t be: Like its boxers (and its filmmaker, for that

matter), Million Dollar Baby is lean, muscular there s not a

drip of fat.

Freeman s warm, straightforward narration lends the tone

of a fable. When Maggie (Swank) enters the gym, we learn all we

need to know: She grew up knowing one thing, Scrap (Freeman)

says. She was trash. And that Scrap is recounting events

long after they happened gives this the air of a film noir (that, and

the shadows that float in and out of every frame). Maggie is

31. She has a nasty trailer park family (the film s one cliche that

feels worn out rather than wellworn). She loves her dead daddy.

Otherwise, we don t know what she did in her 20s, and we don t

know where she got it into her head she could become a boxer.

We can see she has discipline, some talent, and lot of heart. But as Dunn croaks, "Girlie, tough ain't enough." Of course, he comes around and trains her, and the film comes to recognize behind her eagerness there's a flash of scared woman with nothing and no one, and if Dunn won't coach, she says, she might as well buy a trailer and a deep fryer and a bag of Oreos and call it a day.

From this panic, Dunn realizes, he can bottle and shape a champion, so what follows is the inevitable training montage. And the string of fights. And as time-worn as it is, in a movie so emotionally true, you see why.

You also see that the boxing, the trappings, are a vehicle for telling a love story. Not a love story of a romantic sort, but a love story of respect, set in a bleak world where the church and the family doesn't mean a thing compared to the parishioners and the families we create on our own. If this all sounds impalpable and cornball, understand that Eastwood is working on instinct that knows the difference between sentiment and sentimentality, and ensures we don't get lost when he eventually follows his scarier, harrowing instincts.

Million Dollar Baby, above all else, feels like a work that comes out of years of living, and years of experience with people, and knowing what works and what doesn't. It also comes from a director who is still able to be touched when two people connect. The screenplay (by Paul Haggis) is an adaptation of Rope Burns, a book of short stories by Jerry Boyd, a ringside assistant who wrote under the name "F.X. Toole." It was published in 2000 after 40 years of trying. All those great dark corners and forlorn truck stops in the film are courtesy of production designer Henry Bumstead, who turns 90 in March. And for Eastwood, at 74, it summarizes the masculinity that's been his trademark, and the guns-and-fists aggression that he's spent his career as a filmmaker debunking. He's too old for lies - not epiphanies.

This is a flat-out classic.

Contact Christopher Borrelli at: cborrelli@theblade.com

or 419-724-6117.