Living like rock stars: 'DIG!' chases 2 bands through their ups, downs

4/14/2005

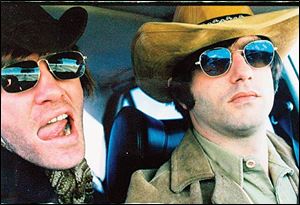

Dandy Warhols leader Courtney Taylor, left, is driven to be a star. Brian Jonestown Massacre leader Anton Newcombe, right, seems destined to self-destruct.

Ondi Timoner's DIG! (Palm, $24.98) - an immediate inductee into anyone's personal Hall of Fame of Rock and Roll Crack-Ups - is a tale of two bands.

Timoner, who premiered DIG! at Sundance 2004 and went on to win that festival's Grand Jury Prize for best documentary, started with an idea that's banal at first glance: Follow two acts across years and document their fortunes. Or lack thereof. But mostly, just observe. That instinct served her amazingly well.

By dumb luck, the two bands she followed from 1996 to 2003, the Dandy Warhols and the Brian Jonestown Massacre, gained some independent credibility, gathered respectable followings, got in bed with record companies, and their stories and trajectories are wouldn't-believe-it-except-it's-true narratives that carry the weight and resonance of great fiction. Think Hoop Dreams - with feedback.

You say you want to be a rock-and-roll star? Well, listen to what I say: DIG! serves as a cautionary tale and virtual textbook about the myths of rock stardom, the pitfalls of ego, and the advantages of playing nice with the right people. The Massacre shoots itself in the foot and collapses, over and over again; the Dandys methodically play the music game and make infinitely less interesting music, but stay consistent.

If you are in a band or know someone who is, it's required viewing. For everyone else, it takes the train-wreck formula of Behind the Music's tales of excess and removes the past tense. You will be sucked in because Timoner was there when one group imploded and the other one sold a few records.

Her subjects share little but a fondness for pop culture name-checking and a quasi-interest in the psychedelic '60s. Speaking of the Massacre, one record exec says without a wink: "They're the greatest '60s revival band since the '60s." Similarities end there.

In one corner is Courtney Taylor, bland and handsome and the leader of the Portland, Ore.-based Dandys. (He also serves as the narrator.) He is unashamed about his ambitions: He wants to be a star, and his swagger seems to say he considers success more like a birthright.

The band signs with Capitol, and you cringe a little when his ego heads skyward. Everyone knows better. One record exec says behind the band's back, nonplussed, "Odds are the Dandy Warhols will fail - like everybody before them."

The Massacre is named for Brian Jones, the Rolling Stones guitarist and professional hedonist, who was found dead in a swimming pool in 1969.

Over the course of the film, the Massacre - but primarily its own talented egomaniac, Anton Newcombe - shows a willingness to live up to its namesake. Its members abuse drugs, pick fights, and melt down before key record executives. They insist they exist outside all the usual cliches of the rock lifestyle, yet you can't help notice they've become a cruel parody of the rock lifestyle.

When you film a band for seven years, it's tough not to get extraordinary footage, and Timoner (who shot 1,500 hours) has a handful of doozies: Massacre members getting into a fight on stage during a concert for Elektra executives who are itching to sign Newcombe. Some of the footage is even local: The Massacre is playing the Magic Stick on Woodward Avenue in Detroit, when the members pick another fight, this time with the wrong patrons.

Newcombe could be described as impossible - that's putting it mildly. But complicating things is that Timoner doesn't have to look far to find someone to attest to the guy's musical genius. He is horrible to most of these people, and they owe him nothing, and so their insistence comes off as genuine.

No more so than Taylor.

He aspires to Newcombe's extraordinary output and his off-the-rails reputation, but not the painful consequences of his self-destruction. DIG! is half comedy and half tragedy, and like the best rock, there's a little of both beneath it all. Their stories contain all the usual conundrums: staying authentic versus selling out, signing for money and less control versus staying personal and innovative.

The Dandys and the Massacre become warring microcosms of the music industry itself. "We're the most well-adjusted band in America," Taylor says, and it's not so much funny as a career imperative: the movie shows that discipline may be as important as talent.

Except when it isn't.

Timoner comes close to making one of the cheapest generalizations in music: that successful bands have hits because they work hard, and screw-ups make art and live in obscurity. But she doesn't buy it, and the fact you probably do not own a CD from either of these groups proves its tastiest irony: You don't either.

FAR AND AWAY: Quick, name the best five movie scenes from the past five years. Does Lost in Translation spring to mind? Bill Murray's confused go-with-the-flow as he shoots a Japanese whiskey commercial and gets little help from his translator?

Sofia Coppola's screenplay was more personal than we realized. Included in the welcome new Criterion edition of Akira Kurosawa's Kagemusha ($39.95) is a sampling of the Suntory Whiskey TV spots her dad, Francis, shot with the legendary filmmaker in the late 1970s. Francis Coppola and George Lucas had been so influenced by Kurosawa, they used their clout to help him land the budget and distribution to make a return to directing after years of silence.

A monster return.

Kurosawa's films - his best known being The Seven Samurai - were never especially modest. After Kagemusha, then Ran in 1985, he became synonymous with impossibly enormous productions. Vast armies clashing on vast plains. That sort of thing.

Without Kurosawa showing the way, Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings might never have looked doable.

Kagemusha tells the story of a thief who imitates a warlord and gains the power of the man he's replaced. It's not Kurosawa's warmest picture, but Criterion's two-disc set argues a good case for its relevance to pretty much any Asian war epic that's reached our shores since. The color is so vibrant, though, I'm less reminded of Hero or House of Flying Daggers than Christo's The Gates in Central Park.

FOREIGN AFFAIR: It's odd going to the movies these days when the most classically foreign film to be released last winter was Steven Soderbergh's Ocean's Twelve (Warner, $27.95). With its Euro locales, hipster veneer, and a playful, bustling story that shuffles chronology and perspective at whim, it's the one that sticks closest to the style of the French New Wave (which is still the cliche that many moviegoers have in mind when they're introduced to a foreign film).

Which is also to say, Ocean's Twelve is the one most reliant on style. Wait, strike that: Pedro Almodovar's Bad Education (Columbia, $26.96) is the work of, arguably, the finest film stylist in the world at the moment. The story of a former altar boy (Gael Garcia Bernal of Motorcycle Diaries) who avenges the sexual abuse he suffered at the hand of a priest, it takes dark material and gives it a definite Hollywood bounce. The intrigue is directly from Hitchcock, the alternate realities are reminiscent of David Lynch, the look is classic noir.

More likely, when a movie is set in a foreign land now, the result is closer to Hotel Rwanda (MGM, $26.98). Don Cheadle plays the manager of a ritzy Rwandan hotel when the Rwandan genocide breaks out. He finds his skills of diplomacy (vital to running a hotel) come in handy when the goal is fending off roving bands of machete-swinging Hutus. It's a shameful, bloody moment rendered in the familiar flat tones and generic uplift of a TV movie of the week.

Contact Christopher Borrelli at: cborrelli@theblade.com

or 419-724-6117.