From the start, 'SNL' jabbed viewers with a sharp shtick

12/7/2006

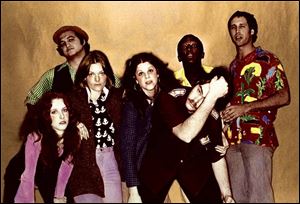

Original Saturday Night Live cast members in 1975 are, from left, Larraine Newman, John Belushi, Jane Curtin, Gilda Radner, Garrett Morris (back), Dan Aykroyd, and Chevy Chase.

Original Saturday Night Live cast members in 1975 are, from left, Larraine Newman, John Belushi, Jane Curtin, Gilda Radner, Garrett Morris (back), Dan Aykroyd, and Chevy Chase.

Before you dig into the massive Saturday Night Live: The Complete First Season (Universal, $69.98), the new eight-disc set of the original 1975-76 episodes as they aired, with the original musical guests - first, pop in disc eight. The menus are awkward (so make sure to click the arrow on each episode or you'll miss hours of footage). Go to "Special Features." Scroll to the bottom, and before you watch a minute of the actual show, click Lorne Michaels' face.

As huge as this set is, the extras are flimsy - a set of screen tests and book of old photos, and this, a short but revealing interview with Michaels, the creator of SNL, and his original cast gathered around him. They were still billed as The Not Ready For Prime Time Players. It was the night before the debut. The interviewer is Tom Snyder, and he takes 30 seconds of a barely four-minute chat by complaining about the heating system in 30 Rockefeller Center. The cast members stare back and nod thoughtfully.

The first thing he asks, turning to Chevy Chase, is "Were you named after the town in Maryland?" Chase does a mock laugh. John Belushi glares at Chase, and Chase ignores him. Meanwhile, Dan Aykroyd, ever genial, points out everyone is very exhausted.

But listen closely.

You can spot the seeds of tensions that would make that season a classic, and steadily tear apart the cast. Snyder asks Michaels about the cast, and the producer says he expects two people here to become stars and the rest to be supporting players - he may have been joking but it's remarkably insensitive because at that point, they were still equals.

Of course, Michaels was almost right. Chase became a star and left the show a year later; Aykroyd and Belushi a few years later. (Bill Murray was still to come.) The Complete First Season proves invaluable, though, as a reminder of the durability of Gilda Radner and Garrett Morris - for starters. It also reminds you how startling SNL looked in 1975, and how startling many of the skits still play. The idea was to provoke, and almost as a reminder, Michaels sends Elliott Gould out, nine shows in, to do a solo soft shoe to the old show tune "Anything Goes," and the audience is still so unfamiliar with network television as a provocateur, it actually applauds the first bars of the number - the way you would during a Las Vegas revue.

Later, there are Muppets.

A song by Patti Smith.

A short by Albert Brooks.

A sensibility was still being worked out here. Richard Pryor gets laughs in a satire of The Exorcist by merely repeating "The bed is on my foot!" It could be Milton Berle. The audience gets it. To be fair, the audience got a lot of it; here was a show in which Ron Nessen, Gerald Ford's press secretary (who hosted), gets a laugh by making oblique references to Catherine the Great and her thing for horses.

But when Morris does a monologue about how viewers should send him (a black guy) money to help with their white guilt, the studio is quiet a long time. Morris mentions his grandfather was lynched, and his relatives were slaves, and he says it with a smile, but there's not a twitter. Then he asks for cash. And the audience exhales.

Saturday Night Live, as an institution, has a problem that is unique to network comedy. It's been on the air so long that fans of the first seasons might enjoy the latest seasons, but the latest generations would almost certainly not get the first seasons. The jokes have dated. The rhythms are stilted. Unless, of course, you were those first audiences. I forgot how Belushi would have to wait until applause died down before he delivered a line - only a few shows in he was becoming a superstar. And I forget how strange it felt for a show to segue from a skit about white fear of integration into a performance by the New Orleans Preservation Hall Jazz Band. It's a scrapbook of a time, and no matter the great seasons still to come, you feel a sharp reminder of just what's been lost.

BETTER NOW THAN LATER: One of the stranger criticisms lobbed at a movie this year was the ostentatious charge thrown by some viewers at Marie Antoinette - since when are movies not supposed to celebrate the hunger for pretty things? Thankfully, Bernardo Bertolucci already made The Conformist (Paramount, $19.98) and his outsized 1900 (Paramount, $19.98) - the former being one of the few certified classics only now making its way to DVD for the first time. They are glorious exercises in excess - 1970's The Conformist (here, in a slightly expanded edition) managing a gut-wrenching study of fascism amid the feathers and leathers.

His two-part, four-hour 1900, with Robert De Niro and Burt Lancaster, was deemed a failure. It's one of those Italian generation sagas that attempt to incorporate decades of Italian history and social upheaval, and like a lot of things in Italy, you get the sense of well-crafted goods and utter chaos. It's shapeless and ambitious. Extras are almost beside the point, and so, with both films, you get a few featurettes.

LAST MINUTE, NO-THOUGHT-INVOLVED-WHATSOEVER GIFT SUGGESTIONS: I'm still puzzling over this. As sincere as it is, World Trade Center (Paramount, $29.99), in which 9/11 gets a happy ending, was made by Olive Stone, who made a virtue of removing politics from the situation. Thank God, at times that try men's souls, we have Talladega Nights: The Legend of Ricky Bobby (Sony, $28.95) which you got a high-definition edition of a few weeks ago if you landed a Play Station 3 (it was included), but plays much nicer in the low-rent, humble tech of ordinary DVDs.

I didn't love it, but I did laugh a lot, and few movies this year have grown as fondly on me. Same goes for The Devil Wears Prada (Fox, $29.99), which finds the smarts you didn't know existed in so-called chick lit. Instead of dismissing the world of fashion, here is a brave picture that actually argues for the frivolousness of it all, as both an art and an industry. Meryl Streep has a scene with Anne Hathaway in which Streep, as the chilly editor of a quasi-Vogue, stops the actress in her Old Navy sweater.

"I'm still learning about all this stuff," Hathaway says, and Streep replies, "This stuff?" She gives a speech winding through the ramifications of a fashion editor's decisions, the jobs that rely on it, and the inevitable politics you take part in when you buy an article of "all this stuff." It's like an argument for the film itself - deceptively fluffy, but walk a mile in its Jimmy Choos, and you have new appreciation.

Contact Christopher Borrelli at: cborrelli@theblade.com

or 419-724-6117.