'We are the godfather of this niche': Experimental films take the Ann Arbor spotlight

3/16/2007

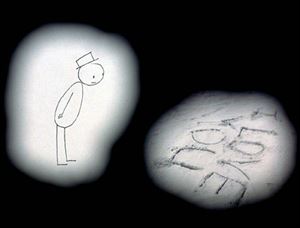

Don Hertzfeldt s Everything Will Be OK is one of the competition films in this year s Ann Arbor Film Festival.

ANN ARBOR - Chris Csont digs a spoon into a virgin pint of Ben & Jerry's. This being Ann Arbor, the cradle of Midwestern activism, of course it's a pint of Stephen Colbert's AmeriCone Dream - the most ideological mix of ice and milk since Cherry Garcia. "I think it has cone in it. Cone dipped in chocolate then broken up or something." He turns to his computer. The glow of his monitor throws shadows on the dark office. Behind him is a bulletin board. In its upper right corner, in a green marker:

"15 DAYS!"

It's 15 days before the 45th edition of the annual Ann Arbor Film Festival - the second-oldest film festival in the United States, which begins Tuesday - and Csont, the festival's operations manager, is one of only two full-time staff members. The other one, Christen McArdle, the festival's director, sits in her own office, nursing her own pint of Ben & Jerry's.

Soon, dozens of avant garde and experimental filmmakers (the festival's bread and butter) swing in town. Soon, there will be retrospectives and dozens of short films that need sequencing and screening. Soon, there will be a one-man history of the festival and an architect who orchestrates five projectors into a sound and light symphony (Bruce McClure, a Whitney Biennial grad). And soon, nearly $25,000 in award money (donated by Gus Van Sant, Michael

Moore, and Ken Burns, among others) will require dividing up.

The mood? Pretty mellow.

Pure college afternoon.

Maybe that's unavoidable.

The festival's old guard - exemplified by Vicki Honeyman, a local hair stylist and the director of many years, until fairly recently - has faded. Most of the staff members now come from the University of Michigan and Eastern Michigan University. They occupy every corner of the festival office, high above State Street, hunched over their laptops bearing half-peeled stickers. The coffee pot is empty, the lamps are old, dorm-room stuff, and the door of McArdle's office even boasts an old Dylan poster.

History hangs high here.

This year, there will be a 60-year retrospective of the seminal west-coast showcase for experimental film, San Francisco Cinematheque. (Incidentally, the San Francisco International Film Festival is the nation's oldest film festival; it turns 50 next month.) For the first time, the festival will screen a pair of midnight movies - nothing less than the '70s freak shows, Alejandro Jodorwosky's classic hallucinogens El Topo and The Holy Mountain.

A state over, here in Ohio, the 31st annual Cleveland International Film Festival started yesterday. Like many a regional festival in a large city, it's poised somewhere between avant garde and mainstream - the flotsam of Sundance is its unintentional calling card. A handful of its hot tickets (Flannel Pajamas, The Ten) will get a reasonably wide release.

In all of the years of the Ann Arbor Film Festival, you'd be hard-pressed to name a film that played the festival that also played a multiplex.

"My stand is, I have no intention of making this more mainstream," McArdle said. It's her second year at the helm. "We own [the experimental] niche. We are the godfather of this niche, the oldest. On a business level, there's no point changing. As for filmmakers: If you make a challenging work you have a hard time finding places to show it. We want to stay that home."

But it's getting harder.

Asked to identify a theme with the submissions this year, McArdle said a number chose to riff on old Hollywood cliches.

But the real theme?

Censorship.

McArdle has inherited a long, colorful history of films being confiscated, police raids, and rampant paranoia at the festival. At the moment, however, it's not an especially romantic feeling. A week before the festival began last year, the private Mackinac Center for the Public Policy sent the Michigan House of Representatives a list of festival films it deemed pornographic. Rep. Shelly Taub (R., Bloomfield Hills) proposed an amendment to the state budget preventing the festival from receiving its annual state arts grant (in 2005, that amounted to roughly $18,000).

McArdle spent part of last summer driving back and forth to the state Capitol in Lansing, until deciding the festival would forgo any government funding.

So look closely this year: The festival's latest poster has the word "censorship" woven into its illustration. The concession stand will sell chocolate Censorship Bars for a snack. And a panel discussion on censorship (featuring Twist of Faith producer Eddie Schmidt) was scrambled together at the last minute. There was a local radio telethon to make up for the funding shortfall the festival faced. But make no mistake: The festival has downsized slightly.

"The truth is, this festival should not have survived this long," McArdle said, curling her legs beneath her. "This art form, the type of film it specializes in - it just should not have survived. Yet it does. Here we are."

The 45th annual Ann Arbor Film Festival runs Tuesday through March 25. Most screenings are in the Michigan Theater, 306 East Liberty St. Screenings are $9, and packages are available. For a complete film and programming schedule: 734-995-5356, or www.AAFilmFest.org.

The 31st annual Cleveland International Film Festival runs through March 25. Most events take place in the Tower City Center, 230 Huron Rd. Tickets to events vary, but standard single screening tickets are $8. For complete film and program schedules, ticket information, and directions: 866-865-3456, or www.Clevelandfilm.org.

Contact Christopher Borrelli at: cborrelli@theblade.com

or 419-724-6117.