Movie review: Eastern Promises ****

9/21/2007

Eastern Promises opens in the criminal underbelly of London. At first, it's the only footing we're given, though even that much is not to be assumed. An insolent young man sits in a barber's chair talking business with a doting old man; a teenage boy stands to one side, shifting his weight. It's not clear what we're looking at - could be the Dickensian London of Sweeney Todd and its butchering hairstylists, the last remnant of tradition in a gun-metal smooth contemporary Britain, or, considering the Eastern European accents, a Slavic remake of The Godfather.

David Cronenberg winks.

He's doing all three, at once.

At some point in the scene we catch ourselves. Cronenberg being Cronenberg, a filmmaker as likely to engage your mind as make it splatter, a warm patina of muted cinematography has been lulling us. Then quietly the air changes and we're waiting for the goose's neck to be wrung, for the first sacrificial lamb to be thrown to the wolves. It's a matter of when. Indeed, we get two, and their legs kick: First, a man has his throat sawed open with (I think) a dull butter knife. It's not pretty. A bit later, on Christmas morning, a dazed Russian girl wanders into a pharmacy asking for help. She's pregnant, and soon hemorrhages on the floor, but not before giving birth. She dies, but the baby is delivered by a midwife, Anna (Naomi Watts), an English woman of Russian descent who lives with her parents. Anna keeps the girl's diary.

Fearing the child will fall into foster care, she looks for clues to the mother's family, which gives us a plot. But it's not about that, either - indeed, what makes the film so engrossing in those first scenes is how familiar it all looks and how out evasive it all plays.

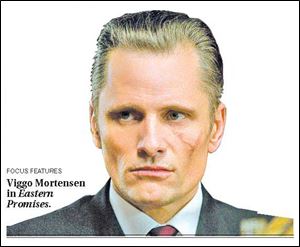

Eastern Promises is about the moral gymnastics of a Russian mobster named Nikolai, played by Viggo Mortensen. He is calm and calculating. He is the heartbeat of those seemingly disparate plotlines, the soul of Cronenberg's first film since 2005's A History of Violence, his instant classic - but more importantly, a movie that reminded us straight-ahead popcorn-friendly genre filmmaking can still unpeel, revealing layers and hidden depths. The new film plays as a companion piece and bears an obvious resemblance: both deal with a criminal enterprise encroaching on an unsuspecting family. Both are told by Cronenberg with an efficiency that's rare in films this complex; indeed, it's overly tight this time.

And both share Mortensen.

At last, it can be said: Cronenberg has found his muse, after a career edging to the 40-year mark. He's found an actor as willing to transform himself as Cronenberg is interested in the ways people transform, morally and physically. What's remarkable about this relationship, at least this time, is how the filmmaker allows Mortensen to become larger than the picture itself - it's the first time the king of Middle-Earth, a team player with the looks of a leading man, has felt as iconic as a movie star.

His hair is swept into horns.

His chin is pure Kirk Douglas.

His eyes smile but the lids hang with sinister weight. More remarkable is how, despite this, Mortensen spends so much of the movie at its margins, waiting to be drawn in. Nikolai is a lackey, a low-level fixer in the Russian mafia, which sells drugs and sex slaves and ensures the old country is never far off. He insists he is a driver, a chauffeur to the boss (Armin Mueller-Stahl, of Shine). He is nothing more, he says: "I am driver. I go right. I go left. I go straight. That is it." It is as if all the sleazy energy he is expected to exhibit as a mafia toady in a Hollywood movie has been transferred into the loose-cannon son of the boss, Kirill (Vincent Cassel) - a kind of hangdog Fredo of the Baltic Sea.

The only juice Nikolai would seem to have with his employers is this friendship with Kirill. But Nikolai knows things. Like how to prune a finger, and how to remove an eyeball from its socket - practical skills. And called forward to act, he unfolds from his statuesque position and glides forward with a quick, lethal blow. He also notices Anna; she has no idea who he is or the nature of the group behind the girl's death. But she sees a flicker of conscience in Nikolai, a humanity he is not willing to show.

The big question behind Eastern Promises is whether Nikolai is a dutiful foot solider or quietly asking the same questions we have, primarily: At what point do evil acts in the service of good leave a person with nothing but evil? In films like The Fly and The Dead Zone and Videodrome, the violence done to a human body in a Cronenberg film came by science and drugs and electronic waves. But as he gets older, the grotesqueries are internal, even handed down through tradition. The Russians who come to England bring with them the best of their homeland, but also the worst - "A slave gives birth to slaves," Nikolai says, dismissive.

The Godfather has come up a lot in the early reviews of Eastern Promises, and that is partly because of its subject and partly because of the intricacies of the relationships between the men. But I think it's mainly because it looks like a genre exercise (both are mob movies, period) but reaches to become so much more. This is not even the film A History of Violence was - the ending is disappointingly abrupt, and Cronenberg never allows its questions to reverberate with a richness he's capable of. But those are small quibbles.

There are moments as memorable and exciting as anything Cronenberg has done, virtuosic scenes that use violence and physical vulnerability not for spectacle but for its maximum sting. The bathhouse scene is already becoming somewhat legendary, and it may well be Cronenberg's peak, a kind of summation of his entire career and his concerns. Nikolai is covered in tattoos, souvenirs of time in Russian prisons. He is naked. A pair of clothed men approach with carving knives. The fight is intimate; the flesh is, um, malleable. And the blood is all red.

Contact Christopher Borrelli at: cborrelli@theblade.com or 419-724-6117.