Fear and loathing in Toronto: Film festival echoes our uneasy mood

9/23/2007

Keira Knightley and James McAvoy in <i>Atonement</i>.

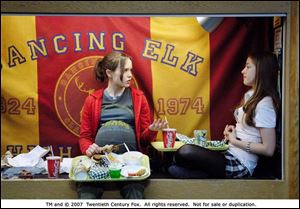

Ellen Page, left, and Olivia Thirlby in <i>Juno</i>.

TORONTO Can t be done.

No way, no how.

Each September, in the days immediately following the 349-ring circus that is the Toronto International Film Festival, after it rolls up its muddied red carpets and calls it a year, once Brangelina has skipped town on a chartered jet and the journalists from Norway have schlepped home, someone will inevitably inquire:

So, how was it?

I just sigh.

There is simply no chance of accurately or neatly summarizing this amorphous, unwieldy blob of a festival, which heralds the start of Oscar season, and featured 350 films spread across 10 days, each accompanied by a steady pounding of marketing drums. It wrapped last weekend. But was there a message to wrap with? A mandate? Or initiative?

A favorite film?

A single image?

Myself, thinking back ...

I picture parades.

Vast armies of cheerful teenagers in crisp matching T-shirts, chanting inspirational slogans, not cranky-looking American teenagers, but scrubbed and nice. In short, genuinely terrifying. Every year during the festival they swarm the clean sidewalks of downtown Toronto. They re chipper and pleasant, young and pimple-free. They high-five each other as they march down Bloor Street and University Avenue, extolling the virtues of a Buddhist lifestyle or a Christian upbringing or just raising cash for Darfur. No sooner does one fade into the distance before another replaces it bearing a new cause or a global calamity.

Keira Knightley and James McAvoy in <i>Atonement</i>.

So thoughtful, so varied.

It made covering Toronto, this year in particular, a surreal experience. I left a Sunday morning screening of the Brian DePalma film Redacted, which finds its story in the rape and murder of an Iraqi family by American soldiers, and soon ran into a parade protesting the United States involvement in Iraq. I left a screening of Lars and the Real Girl, which stars Ryan Gosling as a mentally ill young man who has a relationship with a life-size doll, and found myself sidestepping a group protesting the rampant prescribing of psychotropic drugs. A protest for every taste.

In a city that lacks identity.

Just like its festival.

Because, broken down into genres, the Toronto International Film Festival is really a half-dozen festivals grouped under one umbrella a festival for midnight movie fans, a festival for slow Romanian films, and a festival for big studio blockbusters. Every cinematic constituency is covered. Indeed, for most of its 32-year history, the festival s name reflected this absence of a single identity and was known simply as the Festival of Festivals and that spirit of inclusion remains. This year, for instance, I saw 40 movies, sentimental dramas about immigrants and zombie epics and slick vehicles with George Clooney. I interviewed 20 directors and actors, and slept 21 hours, in total. Which is no way to judge a movie, let alone seriously digest a few dozen. And still, certain broad, overlapping thoughts do gain a little footing.

Promising thoughts.

That Clooney film, for example, Michael Clayton, opening in early October, is a great example of the spirit of social relevance that seems to be sweeping the movie business. It considers the toll of corporate corruption, not merely on innocent lives but on American ideals of morality and social justice. Stylistically and politically, it could have easily been made in the early 1970s, when the social upheavals of the late 1960s and the war in Vietnam could no longer be ignored by a big, bloated studio system.

If Toronto was any indication and each year it tends to be a strong signal of what we ll see in theaters over the next 12 months get used to this. You could read it as a renewed political engagement or a passing bandwagon. Either way, I could have sat through an Iraq-inspired festival alone, and still seen 40 pictures, of various styles. There were ones that approached Iraq without a buffer or even an allegory: Paul Haggis none-too subtle In the Valley of Elah, the follow-up to his Oscar-winning Crash, is a mystery about a returning solider, and on second thought, it ends on an image that could represent the festival:

An upside down American flag.

A signal of distress.

If you chose, escape was possible Toronto had its laughs.

Which caught in your throat.

The teen-pregnancy fable Juno, from the filmmakers of Thank You for Smoking, and the stoner yucks of Smiley Face, from indie stalwart Greg Araki, come with a palpable feeling of being alone in the world displaced and adrift. In comparison, the rock biopics I m Not There (about Bob Dylan) and Control (about the lead singer of Joy Division) might have seemed positively narcissistic if they hadn t been so sharp. Instead, ironically, for a massive dose of narcissism, one need only see Captain Mike Across America, an oddly myopic documentary from Michael Moore about his 2004 tour of election-year swing states. It has scenes shot during the filmmaker s stop at Seagate Convention Centre in Toledo, but avoid it: the picture, the last word on self-aggrandizement, works as neither a rallying shout nor a cultural barometer.

More effective were the films that saw Iraq and America and its president and his policies as pieces of a global puzzle that were upended by the events of Sept. 11, 2001. Rendition, which opens next month, stars Reese Witherspoon as the wife of an Egyptian man quietly smuggled out of an American airport and sent to a secret prison and tortured by the CIA for information he doesn t hold. But like Elah, there s a thudding earnestness to it that finds no room for style or the glancing touch of random insight, and fine actors are left stranded with a sledgehammer.

Which is to be expected.

Less expected were the studio films that took 9/11 as a dark tragedy that continues to unspool and inform. It won t take decades for film scholars or audiences to connect current events with the revenge motifs in Jodi Foster s The Brave One and the upcoming Reservation Road, though the latter takes it further. Directed by Terry George (Hotel Rwanda), it stars Joaquin Phoenix and Jennifer Connelly as a couple grappling with the death of their son after a hit and run. The film s incredible coincidences do it no favors (their lawyer, Mark Ruffalo, happens to be the mysterious driver), but its tone feels very much of these times.

Which is to say, ominous.

The smallness of our world came up repeatedly during the festival, in the gorgeously animated Iranian memoir Persepolis, in David Cronenberg s masterful Eastern Promises, which took the People s Choice Award. Both deal with the cost of globalization, with what is lost from assimilation and what is gained. But you were far more likely to feel a sense of impending doom from a Toronto film than any other emotion. Indeed, if the movies are doing anything right, Toronto suggested, it s that they re capturing how we re coping with changes in the world. Or rather, how we feel about them.

The Savages and Before the Devil Knows You re Dead, both co-starring Philip Seymour Hoffman and opening this fall, find families overspending their way through tragedy, remaining blissfully ignorant of their fluctuating worlds until they can no longer stay self absorbed. If there s an urgency in the tone, it s matched by a feeling of impending collapse. Even the title of one of the festival s best films, Joe Wright s adaptation of the Ian McEwan novel Atonement, seemed pregnant with meaning.

Let s hope so.

The last time American movies were so willing to capture a mood of vague uneasiness American film entered a golden period the late 60s and 1970s, the time of The Godfather and Chinatown and A Clockwork Orange. The question is, can contemporary Hollywood capture its times without becoming a literal throwback to the 1970s? The ennui of Michael Clayton feels straight from All The President s Men, and the psychedelic kitsch of the Beatles musical Across the Universe owes more than a few bell-bottoms to the dippy kitsch of Hair. And stylistically, the soft-focus vistas of Days of Heaven (of Terrence Malick, in general) find a new home in Sean Penn s Into the Wild and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, which stars Brad Pitt as Jesse. And like a Robert Altman picture, it finds room for myth-making alongside a debunking.

Perhaps as a way of making sense of so much free-floating anxiety in the Hollywood ether, I spent the week unable to shake a snippet of dialogue in the upcoming Cormac McCarthy adaptation No Country for Old Men a bloody good return to relevance from the Coen brothers, after years in the creative wilderness. There s been a mass shooting, and bodies are scattered over a Texas plateau. A pile of money is missing, and a killer is blasting his way toward it.

Dread hangs heavy.

Bad times approach.

A classic western set-up.

Tommy Lee Jones, his famous forehead furrowed, is sorting it out, but unlike westerns of decades past, the threat is vague, hard to place more like fate itself than a guy with a shotgun. A deputy blurts: It s a mess, ain t it? And Jones says: If it ain t, it ll do until the mess gets here.

Contact Christopher Borrelli at: cborrelli@theblade.com or 419-724-6117.