Ken Burns reflects on horror of the so-called 'good war'

5/20/2012

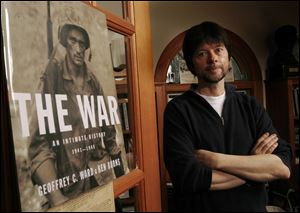

Documentary filmmaker Ken Burns poses at his office.

Ken Burns' 15-hour PBS documentary The War (2007) -- about World War II -- was recently released on Blu-ray by Paramount. Excerpts from an interview:

Q: Since you grew up in the '50s, I was wondering if you played war with your friends.

A: Oh, absolutely. I was filled with the stories of the Second World War, always sanitized and devoid of any of the horrors. My brother and I dug trenches in our backyard and killed Germans with both imaginary and play machine guns and rifles. It was very much a part of my growing up. And this (The War) is in some ways part of the extension of myself growing up and understanding what really happened.

I think we have tended to romanticize the Second World War. We call it the "good war." It was actually the worst war ever. We talk about it as the greatest generation, but then we don't say what did that greatest generation do? Fortunately, there have been good books and there are movies like Saving Private Ryan in which Steven Spielberg is willing to dive beyond. Our series was an attempt to do the same thing, to look at the greatest cataclysm in human history, the Second World War, not from the perspective of presidents and generals, but from so-called ordinary people from four geographically distributed American towns.

Q: With so much already having been written and researched about World War II, did you uncover anything that surprised you?

A: Every day. You know, someone pointed out about three-quarters of the way through that this was the first time we made a film in which there already were a thousand films on the subject. Usually we are like the first or the second to do something about it. Now with the release of the Blu-ray by Paramount, it's really going to be in your living room. That was our idea, to bring the experience of the war home. I want everybody to have an opportunity to see it and understand what that greatest generation went through.

Q: Because there was so much material, did that become a challenge in making the film?

A: Sure, of course. Some films -- when you work in the 19th century or late 18th century -- it's the absence of material which is the tyranny, and you forge new things. Sometimes it's too much material. What we had, and what PBS permitted us, was the luxury of time. We spent years. The stuff you see on the History Channel, they are taking off the main table of (World War II) highlights. We could ask for the negative and look at all the outtakes and find out that it was originally shot in color or the amazingly famous footage of the guy dropping at Omaha Beach; there's actually not three seconds of that, but seven seconds, and two other Americans drop and that makes it exponentially more painful and more meaningful to us. Those are the types of things we're able to do, so yes, it's always a huge management job.

Q: What do you think it is that viewers gravitate to when it comes to war?

A: Here's the thing -- it is one of the great human paradoxes. When your life is most threatened and violent death is possible at any moment, life is vivified to a height not felt anywhere. Not in love, not in sex, not in anything. That vivification manifests the worst of human behavior, but it also manifests the best. So war becomes a kind of concentrated, super-concentrated version of the human experience. We are drawn to war because we can't believe that human beings do this and yet we know that we do this.

How can you call the death of 60 million human beings a good war? It is because we felt the cause was right and all subsequent wars -- Korean and Vietnam and the Gulf Wars, we weren't quite sure of the objectives -- here we knew what it was. But this was more ghastly than all those other wars put together times 10.

Q: So much goes into producing a documentary like this. When it's finished, are you ready to let it go?

A: It's hard. Yes, you have to do that. People say works of art aren't finished; they are abandoned. And there's a bit of truth to that. You work at it and you say, "This is what I can do to the best of my abilities right now," and you let it go.

It's not so much you feel remorse at letting it go as it goes out in the world like your own children. I don't know about you, but I've got two daughters who are grown and two daughters still at home. They are out in the world and I have a different relationship to them. They are on their own, but you are still nonetheless proud of them. One has made me a grandfather, so that's really great.

A nearly 90-year-old veteran came up to me in the airport and looked like he'd seen a ghost. He said, "Ken Burns?," and his voice was breaking. I nodded and he couldn't say anything. He just put his arms around me and he started to cry. I hugged him back. I started to cry and we just looked at each other. We just split up and there was nothing to be said. You realize that's the reward of this work. We all have to know what our fathers and grandfathers went through.

Q: Did your father ever see combat?

A: No, he was so fortunate. He arrived in Europe April of '45. He missed it, but I still think the devastation and the destruction was too much for him. The stories he told were the broadest painted stuff. We fought the idealized good war in the backyard. Doing this opened it up to what it was really like -- hell, hell, hell on Earth.

Q: And when you think of the age of the soldiers, they were boys.

A: I was interviewing a guy and he would say, "And then these kids would come up." I'd say, "Paul, what are you talking about?" This is Paul Fussell, the great writer on the Second World War and a combat infantryman on the line, meaning he was a good killer. I would say, "Paul, what are you talking about? How old are these kids?" He said, "18." I said, "How old are you?" He said, "19."

That one-year difference was the difference between, let's say, 20 years old and 60 years old. I mean, it was terrifying to do the interview with him. I had a pit in my stomach; my heart was pounding. I didn't know what I was going to do. I couldn't breathe. Can you imagine? I'm safely in the oughts (2000s) doing an interview in the comfort of a room, but he's becoming 19 years old before my very eyes.

The first two rolls he is being professorial, and all of a sudden I looked at him and I said, "You saw bad things." His cheek started to twitch, his voice started to crack, and he just went back in time and was a 19-year-old killer. It's always about nearly being killed, watching your friends die and killing other people. It's the worst thing you could possibly do.

Q: Do you find parallels with the present when you are in the past?

A: Of course, but the Bible has told us this for 5,000 years. It's Ecclesiastes 1:9 -- "What has been, will be again." What's been done, will be done again. There's nothing new under the sun. Human nature remains the same. My job is not to be a political filmmaker. That only talks to one side of it. It's to speak to all Americans. I don't care what your political orientation is; I want to share with you a story. I am trying to reach everybody.

The Block News Alliance consists of The Blade and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Patricia Sheridan is a writer for the Post-Gazette.

Contact her at: psheridan@post-gazette.com.