Julie Harris keeps a poet's voice alive

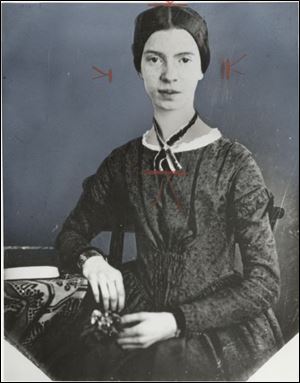

4/1/2001She was a reclusive homebody. A self-proclaimed “nobody.”

She looked after her sick mother, baked for every neighborhood occasion, and tended to the garden. And as she approached her middle years, she mysteriously pulled in her wings so tightly that she never ventured beyond the two-block area of her family home.

But the essence of Emily Dickinson was such a wonder and her brilliance so worthy of celebration that Julie Harris has introduced the poet to hundreds of thousands of people in the last 25 years. Harris brings her 1977 Tony-award winning one-woman show, The Belle of Amherst, to Toledo's Valentine Theatre Wednesday and Thursday evenings.

What does she love about Emily?

“Just about everything,” Harris said from a hotel in Scottsdale, Ariz., last week. “I think she's a great poet. She talks about what's important in our lives - of love and loving one another.”

Emily Dickinson had 'an abiding sense of spirtuality.'

Harris does not believe Dickinson suffered from a psychological disorder that prevented her from leaving home. “She had a territory that was hers,” Harris said. “And she had a very full life within that scope.” She often went next door to visit with her brother, Austin, his wife, Susan, who was her best friend, and their children. After her parents died, she shared the family home with her sister, Lavinia.

Harris, 75, understands how Dickinson filled the days on her small island. The actress spends her days studying new plays, brushing up on her current script, visiting with friends, seeing new movies, and attending the theater. And she devotes about 21/2 hours a day writing a dozen or more letters and notes. No quick and easy e-mail for her. “I have that in common with Miss Dickinson,” she said.

From 17th-century Puritan stock, Dickinson was born and raised in Amherst, Mass. Her father was a Yale-educated lawyer and her grandfather helped found Amherst College. She penned nearly 1,800 poems, most of them short, insightful observations into nature, life, love, death, and eternity. Only a handful of her poems were published while she was alive, and those were done by renegade friends against her wishes. Dickinson died in 1886 at the age of 56 from kidney disease.

If Dickinson were living today, Harris thinks she would have been strong enough to avoid the depression that led some 20th century female poets, such as Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton, to commit suicide. “She had an abiding sense of spirituality, although she refused to belong to a church.”

She rejected her family's Calvinism as “too much blood and thunder,” Harris said. But the books she kept at her bedside and her steady sources of inspiration were the Bible and the works of Shakespeare.

Harris' secret for keeping the show fresh after hundreds of performances lies within Dickinson's words. “The material is so remarkable. And it's a good story. I start the story talking about her black cake - a wonderful fruitcake made with currants and raisins and full of brandy,” she said. “I get enthralled. I think of myself as a messenger for her.”

Harris makes her home on Cape Cod, Mass., but grew up in a 30-room mansion on Lake St. Clair in Grosse Pointe, Mich. One of three children baptized as Episcopalians, her father, like Emily's father, was a Yale graduate. He made money by playing the stock market. Her mother was a nurse. Her parents often took their children to the theater in Detroit where she became smitten with the great actors of the 1930s and 1940s. “I saw these plays and was thrilled by it,” she said.

She attended theater camp in Colorado during the summers and after high school, went to Yale to study drama before landing a part in a Broadway show when she was 20.

Harris went on to win Tony awards for I Am a Camera (1952), The Lark (1956), Forty Carats (1969), and The Last of Mrs. Lincoln (1973). Among her film credits are Housesitter, in which she played Steve Martin's mother, and East of Eden in which she played opposite James Dean. For seven years, she appeared on Knots Landing as Lilimae Clements.

Married three times but currently single, she has one son, Peter Gurian, 45. “He's very bright. A sort of country squire,” she said.

She benefits from having an abundance of energy, good health, and an appetite for work. “By the grace of God and taking care of myself as best I can,” she said. “I take lots of vitamins, eat carefully, and get lots of rest.”

After the current tour closes in Newark, N.J., on Easter, she leaves for Chicago where she'll do a new play, Fossils, about two elderly women who form a friendship.

“The Belle of Amherst” performance is Wednesday and Thursday at 7:30 p.m. at the Valentine Theatre. Tickets are $15, $30, $40, and $45. Information: 242-2787.